Posts Tagged ‘Pacific’

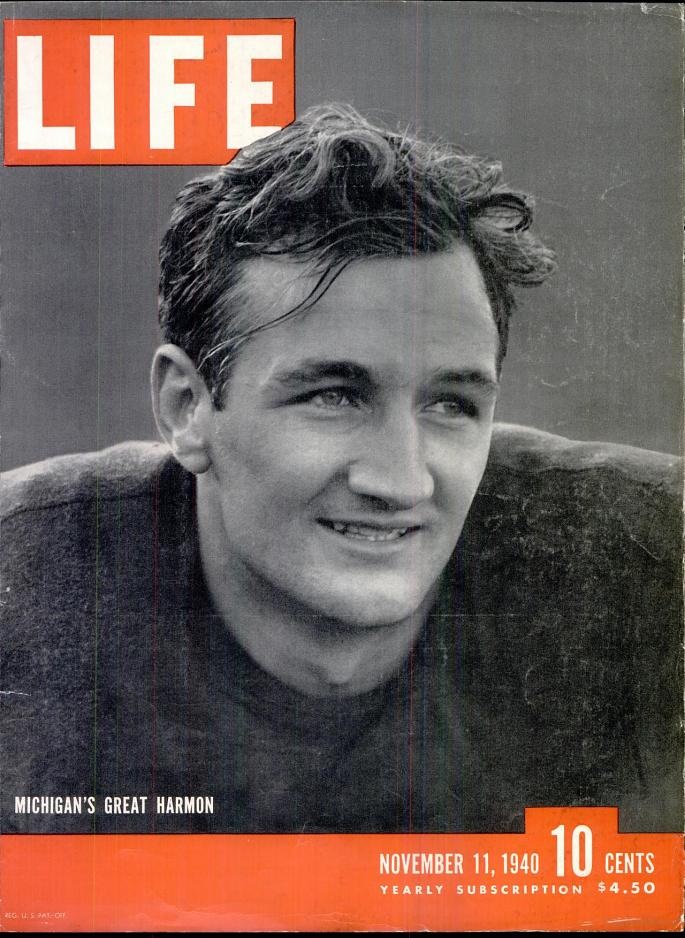

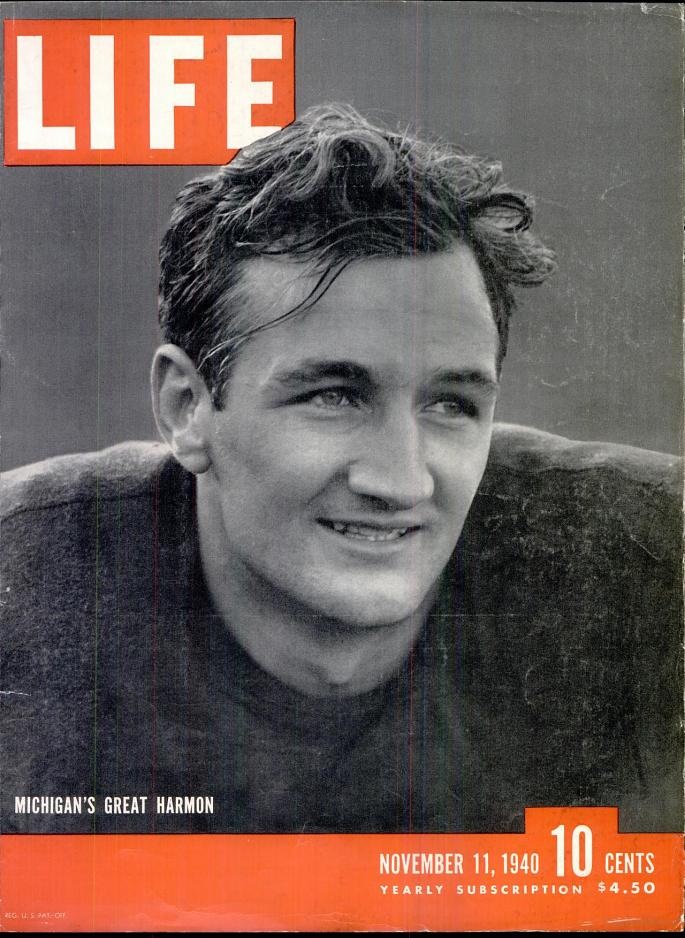

April 10, 1943 – Former all-America tailback at the University of Michigan and Heisman Trophy winner, Tom Harmon (US Army Air Corps) was the only member of his crew to survive a crash over Suriname due to weather conditions.

More About Tom Harmon –

Excerpt from Tom Harmon’s Obituary, The New York Times, March 17, 1990

Twice during World War II he was reported missing in action. In April 1943 he crashed into the jungles of Dutch Guiana, which is now Suriname, and marched alone through swamps and rain forests four days before he was rescued by natives.

Later that year, he bailed out of his P-38 fighter plane over China when it was shot down in an air fight. When he reached the ground, there were bullet holes in his parachute, and he pretended he was dead to discourage the enemy pilots from further attacks. He was smuggled back through Japanese-held territory to an American base by friendly Chinese bands.

When Harmon married Elyse Knox, an actress, on Aug. 26, 1944, the bride used the white silk and white cords from his parachute in her wedding gown.

After the war, Harmon received a $7,000 tax bill for earnings on the movie he had made in 1941. He accepted a $20,000-a-year offer from the Los Angeles Rams football team and performed for them through two unimpressive seasons. Wartime leg injuries robbed him of his former speed and power.

After ending his playing career, Harmon spent the rest of his life as a sports broadcaster in radio and television, based mainly in Los Angeles. In 1974, he joined the Hughes Television Network as a sports director, hired to coordinate sports programming and to serve as a commentator at major golf tournaments.

”Sports broadcasting was the only job I ever wanted,” he said. ”It was the thing I loved because it put me among people I knew and wanted to be with.”

The Michigan sports blog MGOBLOG also credits Harmon as the man who “made NCIS possible by fathering son, Mark.”

Tom Harmon (top row, center) and crew at Atkinson Field

Ahn Sehong had to go to China to recover a vanishing — and painful — part of Korea’s wartime history. Visiting small villages and overcoming barriers of language and distrust, he documented the tales of women — some barely teenagers — who had been forced into sexual slavery during World War II by the Japanese Army.

Read the rest of the article.

Image and excerpt from The New York Times.

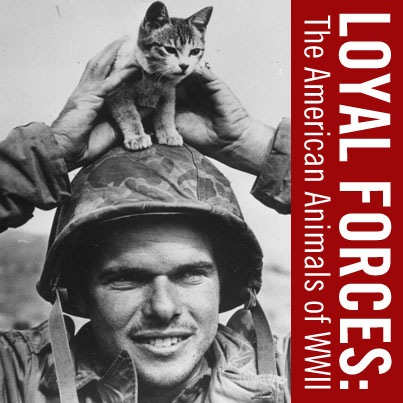

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Thursday, March 7, 2013

5:00 pm Reception | 6:00 pm Presentation

US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center

Join The National WWII Museum to celebrate the launch of Loyal Forces: The American Animals of WWII, written and compiled by the Museum’s very own Assistant Director of Collections, Toni M. Kiser and Senior Archivist, Lindsey F. Barnes.

At a time when every American was called upon to contribute to the war effort — whether by enlisting, buying bonds, or collecting scrap metal — the use of American animals during World War II further demonstrates the resourcefulness of the US Army and the many sacrifices that led to the Allies’ victory. Through 157 photographs from The National WWII Museum collection, Loyal Forces captures the heroism, hard work, and innate skills of innumerable animals that aided the military as they fought to protect, transport, communicate, and sustain morale. From the last mounted cavalry charge of the US Army to the 36,000 homing pigeons deployed overseas, service animals made a significant impact on military operations during World War II.

This event, held in the brand new US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center, is free and open to the public.

The Last Cavalry Charge

In 1941, as the Japanese continued to wage war on China, their need for oil, rubber, and other natural resources became desperate. Both the United States and Great Britain had placed embargoes on these items and frozen Japanese assets, making it increasingly harder for them to acquire the raw materials they needed to continue their war efforts in China. The Japanese took bold steps to ensure their gains in China would not be lost by invading the island nations in the Pacific. They hoped to secure oil from Borneo, Java, and Sumatra, along with rubber from Burma and Malaya. To secure shipping lanes for these raw materials, Japan invaded the American-controlled Philippine Islands.

Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright was commander of the Philippine Division, assigned to the post in 1940. Nicknamed “Skinny,” Wainwright was a 1906 graduate of West Point and a World War I veteran. His assignment as commander represented a significant achievement for Wainwright, with about 7,500 soldiers under his command. These soldiers were mostly Philippine Scouts, or native Filipinos who fought under the American flag. Also assigned to Wainwright was the 26th Cavalry Regiment, one of the last horse-mounted cavalries in the U.S. Army. Wainwright was a traditionalist when it came to the cavalry. His sentiments were that horse-mounted cavalry were some of the finest, most select, and most well-trained soldiers in the military. In his memoir, General Wainwright’s Story, he says of this unit that they were “to fight as few cavalry units ever fought.”

One officer of the 26th Cavalry Regiment was Lt. Edwin Price Ramsey. Like Wainwright, Ramsey believed the horse-mounted cavalry to be a superior unit of the military. His passion to remain in a mounted unit motivated him to volunteer to go to the Philippines in April 1941. He was assigned to lead Troop G, 2nd Squadron, of the 26th Cavalry Regiment. His troop consisted of twenty-seven men, all Filipinos, whom Ramsey was to train in mounted and dismounted drill. The men were disciplined, some having served close to thirteen years in the 26th, and Ramsey enjoyed working with them. It was with this troop that Ramsey was assigned his horse Bryn Awryn, a chestnut gelding fifteen and a half hands tall and with a small white blaze on his forehead. Bryn Awryn was powerful and well schooled, clever and aggressive, with the ability to turn on a dime.

(more…)

Rear Admiral Norman Scott, victor of the Battle of Cape Esperance

Today marks the 70th anniversary of the start of the Battle of Cape Esperance, the second major naval battle to occur at night during the Guadalcanal campaign. Although strategically unimportant, the American victory at Cape Esperance proved to be a much needed morale boost for the US Navy.

Prior to the Battle of Cape Esperance, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the uncontested master of the water around Guadalcanal at night. Japanese ships used the cover of darkness to bring supplies and reinforcements to the men struggling to recapture Henderson Field from American soldiers and marines. These resupply runs, known as the “Tokyo Express” frequently included bombardments of Henderson Field by Japanese cruisers and destroyers.

After two months of uninterrupted trips to Guadalcanal, the Japanese had grown complacent. And so it was that on the night of 11-12 October 1942, a Japanese bombardment force of three heavy cruisers and two destroyers was ambushed by an American task force under Rear Admiral Norman Scott.

Scott’s force of four cruisers and five destroyers first spotted the Japanese warships at 11:43 p.m. on the 11th. The Japanese commander mistakenly believed that the unidentified ships were a Japanese resupply convoy, so he ordered his ships to turn on their recognition lights. Immediately after the lights went on, the Japanese ships were deluged by American shells. What followed was nearly forty minutes of chaos as both sides fired at shell flashes and launched torpedoes in the darkness.

USS Boise’s scoreboard, which claims six Japanese ships sunk at Cape Esperance. In reality, only five Japanese ships fought at Cape Esperance, and only two of those were sunk.

The Japanese cruiser Furutaka and the destroyer Fubuki were sunk, and the cruisers Aoba and Kinugasa were damaged during the battle. On the American side, the USS Duncan DD-485 was sunk, and the USS USS Salt Lake City CA-25, USS Boise CL-47, and USS Farenholt DD-491 were all damaged.

Tactically, the Battle of Cape Esperance was an American victory. The Japanese bombardment force was turned back after suffering major damage. Strategically though, Cape Esperance was a minor victory at best. Although Scott’s force bought Henderson Field one night’s reprieve from bombardment, he did not stop the Tokyo Express. In fact, a Japanese reinforcement convoy landed troops and supplies on Guadalcanal while the battle raged. However, the Battle of Cape Esperance provided a critical morale boost for the US Navy when it was desperately needed. Norman Scott and the ships under his command put the first dent in the Imperial Navy’s seemingly impenetrable armor 70 years ago today.

Posted by Curator Eric Rivet

The Wasp gets hit hard, 15 September 1942. Gift of Lionel Taylor, 2010.396.005

The USS Wasp (CV-7) was laid down on 1 April 1936, and commissioned on 25 April 1940. The [exceptionally small] aircraft carrier was built according to proportions agreed upon at the Washington Naval Conference in 1922. For the Wasp, this meant displacing no more than 15,000 tons. To build such a light aircraft carrier meant doing without much armor at all, which certainly contributed to the ship’s demise on this day 70 years ago, 15 September 1942.

Before America declared war, the Wasp was one of several ships that participated in the transport of US aircraft to Iceland in late summer 1941. After months spent training and patrolling the Atlantic—and an American declaration of war—Wasp was sent once again to ferry aircraft on behalf of the British RAF for actions at Malta in April 1942, and a return trip a month later to replace heavy aircraft losses in the first go-round.

After losing two carriers in naval combat (Lexington at Coral Sea and Yorktown at Midway), the Wasp was suddenly in high demand in the Pacific. With the American invasion of Guadalcanal in the works by July 1942, the Wasp was assigned to Admiral Fletcher’s force. Beginning in the early hours of 7 August 1942, Wasp’s Avengers, SBDs, and Wildcats hit several Japanese positions throughout the Guadalcanal islands, taking out 24 enemy aircraft at the cost of 4 of their own.

On 15 September 1942, Wasp along with the only other carrier available in the Pacific, the Hornet, was on escort duty ensuring the landing of 7th Marines on Guadalcanal proper. She was struck by several torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-19. Being as Wasp was lightly armored due to its construction limitations, she was particularly vulnerable. On top of that, she was hit much like the battleship Arizona was at Pearl Harbor, struck near the magazine causing huge explosions from ammo and gasoline. The fires could not be fought and the order to abandon ship was given. After a successful evacuation, the Wasp soon rested on the floor of the waters off Guadalcanal. Though her aircraft in the sky at the time of the attack were able to make emergency landings elsewhere, the rest of the planes the Wasp carried were lost with the ship. Nearly 200 brave sailors lost their lives with the sinking of the Wasp, with many more wounded. Today, we remember those men.

This post by Curator Meg Roussel

Beginnings…

When the Empire of Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese thought that they had scored a great victory. In truth, the Japanese had sealed their fate and assured their defeat by not completing the job of destroying the Pacific Fleet. While it is true and undeniable that the Japanese did deal the Pacific Fleet a hard blow, that blow was hardly decisive. The Japanese aviators that attacked Pearl Harbor that morning left the job unfinished. While the battleships lay smoking and sinking in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor, the American aircraft carriers were either at sea ferrying aircraft to far flung Pacific bases, or back home, safe in the continental forty-eight. The failure of the Japanese to eliminate the threat of American aircraft carriers would come back to haunt them 6 months later off Midway Island.

The Japanese Plan of Attack

Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto knew that in order for Japan to have a free hand in the Pacific, what was left of the American Pacific Fleet, especially its aircraft carriers must be destroyed. Yamamoto first hatched his Midway plan in March. His plan was to lure the American aircraft carriers out of Pearl Harbor so that the Japanese carrier strike force could destroy them in one final decisive battle on the high seas. Yamamoto decided that the Japanese objective should be a place that put Hawaii in imminent danger. Surely, the Americans would come to the defense of an island that put their most precious remaining base in jeopardy. Yamamoto settled on the island of Midway as the objective of his attack.

Admiral Yamamoto devised that the Japanese carrier strike force would eliminate Midway’s island-based air power, allowing his army to invade and occupy the island rapidly. Once word of the attack on Midway reached Hawaii, the island would already have been captured and the Japanese carriers would be waiting for the American carriers to come to Midway’s rescue. In the ensuing battle, the Japanese carriers would destroy what was left of the Pacific Fleet. On May 27, 1942 the Japanese first carrier strike force, known as Kido Butai, weighed anchor at Hashirajima Harbor and set off for what they thought would be the deciding victory in their war with the United States.

(more…)