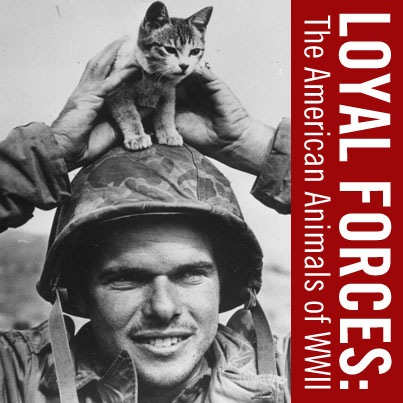

Loyal Forces – The American Animals of WWII

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Thursday, March 7, 2013

5:00 pm Reception | 6:00 pm Presentation

US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center

Join The National WWII Museum to celebrate the launch of Loyal Forces: The American Animals of WWII, written and compiled by the Museum’s very own Assistant Director of Collections, Toni M. Kiser and Senior Archivist, Lindsey F. Barnes.

At a time when every American was called upon to contribute to the war effort — whether by enlisting, buying bonds, or collecting scrap metal — the use of American animals during World War II further demonstrates the resourcefulness of the US Army and the many sacrifices that led to the Allies’ victory. Through 157 photographs from The National WWII Museum collection, Loyal Forces captures the heroism, hard work, and innate skills of innumerable animals that aided the military as they fought to protect, transport, communicate, and sustain morale. From the last mounted cavalry charge of the US Army to the 36,000 homing pigeons deployed overseas, service animals made a significant impact on military operations during World War II.

This event, held in the brand new US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center, is free and open to the public.

The Last Cavalry Charge

In 1941, as the Japanese continued to wage war on China, their need for oil, rubber, and other natural resources became desperate. Both the United States and Great Britain had placed embargoes on these items and frozen Japanese assets, making it increasingly harder for them to acquire the raw materials they needed to continue their war efforts in China. The Japanese took bold steps to ensure their gains in China would not be lost by invading the island nations in the Pacific. They hoped to secure oil from Borneo, Java, and Sumatra, along with rubber from Burma and Malaya. To secure shipping lanes for these raw materials, Japan invaded the American-controlled Philippine Islands.

Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright was commander of the Philippine Division, assigned to the post in 1940. Nicknamed “Skinny,” Wainwright was a 1906 graduate of West Point and a World War I veteran. His assignment as commander represented a significant achievement for Wainwright, with about 7,500 soldiers under his command. These soldiers were mostly Philippine Scouts, or native Filipinos who fought under the American flag. Also assigned to Wainwright was the 26th Cavalry Regiment, one of the last horse-mounted cavalries in the U.S. Army. Wainwright was a traditionalist when it came to the cavalry. His sentiments were that horse-mounted cavalry were some of the finest, most select, and most well-trained soldiers in the military. In his memoir, General Wainwright’s Story, he says of this unit that they were “to fight as few cavalry units ever fought.”

One officer of the 26th Cavalry Regiment was Lt. Edwin Price Ramsey. Like Wainwright, Ramsey believed the horse-mounted cavalry to be a superior unit of the military. His passion to remain in a mounted unit motivated him to volunteer to go to the Philippines in April 1941. He was assigned to lead Troop G, 2nd Squadron, of the 26th Cavalry Regiment. His troop consisted of twenty-seven men, all Filipinos, whom Ramsey was to train in mounted and dismounted drill. The men were disciplined, some having served close to thirteen years in the 26th, and Ramsey enjoyed working with them. It was with this troop that Ramsey was assigned his horse Bryn Awryn, a chestnut gelding fifteen and a half hands tall and with a small white blaze on his forehead. Bryn Awryn was powerful and well schooled, clever and aggressive, with the ability to turn on a dime.

Lt. Edwin Price Ramsey and his horse, Bryn Awryn, 1941. Courtesy Lt. Edwin Price Ramsey.

On December 7, 1941, in the Philippine capital city of Manila, Ramsey and Bryn Awryn and the Troop G team played a friendly game of polo against the local Manila Polo Club. General Wainwright was on hand to keep score. As the day dawned on December 8, they received word of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, where the local time was 6 a.m., December 7. Just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese began various air assaults on the Philippines. One particular attack at Clark Air Field, located just north of Manila, raged for two hours. It destroyed almost the entire airfield and hit a store of about two hundred U.S. Navy torpedoes that were needed to repel the Japanese navy. There were some five hundred casualties from the raid. The Japanese began landing on December 10, 1941, on the northern part of the island of Luzon.

Official war plans held that the army’s priority was to protect the entrance to Manila Bay. Next, they should prevent Japanese troops from landing on Luzon. If they were unable to do so, they should begin various delaying maneuvers to allow as many troops as possible to safely withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula. As they went, they were to hold back the Japanese from entering Bataan. Plans also accounted for the moving of ample supplies to Corregidor to keep the troops provisioned for six months.

The traditional role of the cavalry is to delay the enemy and defend territory. The 26th Cavalry would be central to the war plan. The regiment would also be used to provide reconnaissance and security, and to raid, attack, and pursue the enemy. However, the mounted cavalry were at a disadvantage considering the terrain of the central Luzon, where much of the battle would take place. The open, muddy plains of the island’s center were much more suited to tanks and artillery, but significant numbers of these were not available to Wainwright at the time.

As Clark Air Field was being bombed, Troop G was moving out of Fort Stotsenburg to the village of Bongabon about 120 miles northeast. Troop G was to relieve Troop B, which was headed back to Fort Stotsenburg. As Ramsey’s troop reached Bongabon, he was given orders to defend Baler Bay about fifty miles farther northeast. Just over two weeks later, Ramsey and his mounted troops were ordered to withdraw to Bongabon, as the Japanese had come ashore on the western side of the island at Lingayen Gulf. The majority of the 26th had been battling the Japanese for days on the western side, taking heavy losses.

Troop B along with most of the rest of the 26th fought hard to stave off more Japanese landings in Lingayen Gulf. They worked with a small tank force to hold the city of Damortis; however, anti-tank fire allowed the Japanese to take control of the city. Now the Japanese were advancing from two directions on the town of Rosario—along the coastal road from Damortis and inland from forces moving south. The Philippine Scouts continued to perform delaying maneuvers that allowed their troops to move out of the area.

In the Philippines, Japanese air assaults had decimated the air force component of the U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), and therefore little could be done to stop or even hinder the invading Japanese forces. Reinforcements from the USAFFE struggled to get to the Philippine Division and the 26th Cavalry Regiment. During the delay, the Filipino line broke and troops fled to the rear, abandoning their guns. Troops were pushed twenty miles south to Binalonan. Here, however, the 26th Cavalry was able to stop the advancing Japanese troops despite their lack of anti-tank weapons. The regiment routed the Japanese infantry and inflicted heavy casualties. Even with more tanks and troops, the Japanese were unable to advance.

It was time to retreat to Corregidor in accord with the WPO-III plan. Part of the plan was an orderly withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula. The plan laid out five defensive lines that were to be held by the troops. As troops and supplies came through the lines, the army was to fall back to the next line, destroying roads and bridges as they went. In particular, Wainwright had to ensure that troops in the south had time to cross the central plain and reach the peninsula. If the troops did not make it, or Wainwright fell back too soon, he would cut off half of the troops on Luzon. Each line was strategically placed to take advantage of the island’s topography. All lines fell on high ground and were about a day’s march apart. The plan called for Wainwright to hold a line only long enough for the Japanese to prepare for an attack. Just as they were ready, Wainwright was to move, thus subverting the attack. The aim was merely to delay the Japanese rather than try to defeat them.

As Wainwright was on the western side of Luzon steadily falling back to the Bataan Peninsula, Ramsey was on the eastern side of the island, trying to ensure that his Troop G made it over to Bataan before the Japanese troops pinched him off from the peninsula.

By New Year’s Day 1942, they were ordered into one of Wainwright’s lines. There were only enough horses for three mounted troops; everyone else was transferred to a motorized unit. Ramsey still had Bryn Awryn and was named commander of Troop G. Their charge was to guard Porac, one of two key towns at the top of the Bataan Peninsula. Ramsey and the men of Troop G were to keep the Japanese on the western side of Luzon from entering Bataan. They fought hard for days on little sleep and scarce supplies of food and forage for the horses.

On January 4, 1942, a huge push by Japanese forces under the command of General Masaharu Homma crumpled the 21st Infantry Division. The loss of the 21st and their subsequent crossing of the Layac River put the 26th in a desperate rearguard fight. As soon as the regiment crossed the river, Wainwright ordered the bridge destroyed. It was vital to hold this new line at the Layac River so that more troops and supplies could make their way down the peninsula. Ramsey and the 26th continued to stay on the western side of the island. They had little natural cover and on January 7 found themselves in the midst of a pitched battle. The U.S. 23rd Field Artillery was behind them shelling the Japanese line, while the Japanese, in front of Ramsey, were returning fire. Shrapnel began to fall on the men and horses, shredding the horses’ sides. The horses screeched and galloped away in fear. The barrage continued for eight hours with horses and men being hit. Two men were killed and several wounded; twenty-one horses were killed. Bryn Awryn survived. The 23rd Field Artillery had been annihilated, losing four of its five guns.

The next days of the 26th Cavalry were spent in a desperate scramble to rendezvous with the other infantry division in the area. They struggled through dense jungles and deep ravines. Often the men had to lead their horses as the trails were steep and difficult to negotiate. During this time the men went without eating. Ramsey wrote, “Every scrap of food we found we gave to our mounts, for to a cavalryman his horse is his survival.” On January 9 they were able to connect with scout cars from their regiment. Upon meeting up with his regimental commanders, Ramsey learned that the cavalry’s delay tactics had worked and Wainwright’s line was in place. The remaining men of the 26th were to move on and continue to protect the western flank of the defense line.

Bataan was now filled with more than a hundred thousand troops and civilians escaping the Japanese. The four-hundred-square-mile peninsula was packed with people, but supplies were scarce. By mid-January it was estimated that there was only enough ammunition, food, and forage for the animals to last four months. At the end of January, that estimate dropped to just an eleven-day supply. There were constant reassurances that a convoy of ships was due to bring aid and supplies and also to get troops off the island. What many did not realize was that the bombing of the Pearl Harbor fleet meant there were no ships to come to their aid. One fatal flaw of the war plan was the heavy reliance on the ships of Pearl Harbor to rescue those in the Philippines.

On January 10, Ramsey and the 26th arrived in Bagac and received word that the Japanese had landed more troops farther north at Olongopo. They provisioned their horses and began searching the countryside of the western coast of Bataan. They were on half rations, exhausted and growing leaner. Ramsey states, “By January 15 the animals were scarcely able to lift their feet over the vines that clogged the trails, and the troopers slumbered in their saddles.” It was painful for Ramsey to watch the flanks of Bryn Awryn subside and his haunches droop.

Troop G returned to headquarters and was given a much-deserved rest. Ramsey, however, with his indispensable knowledge of the terrain, stayed on to lead the remnants of Troops E and F with twenty-seven weary Filipino cavalrymen. General Wainwright gave orders to reoccupy the village of Morong. Wainwright remembered Ramsey’s skill at polo from the match held in December and ordered him to take his unit to reconnoiter the village before troops moved in. The dry season had come to Bataan, and as Troop E moved out, the dust from the coastal road clogged the nostrils and coated the throats of the horses.

Ramsey’s platoon was in the lead and reached the village first. It initially looked deserted, but as the platoon moved toward the village’s center, the men were bombarded with rifle and automatic-weapons fire. The Japanese had just made it to the center of Morong, and Ramsey could see hundreds more Japanese soldiers wading through the Anvaya Cove tributary and entering the village. He knew that a charge was his troop’s only hope. The shock of the mounted charge has for centuries been crucial to its success. The training of the 26th made it instinctual. Ramsey describes the charge:

I brought my arm down and yelled to my men to charge. Bent nearly prone across the horses’ necks, we flung ourselves at the Japanese advance, pistols firing full into their startled faces. A few returned fire, but most fled in confusion, some wading back into the river, others running madly for the swamps. To them we must have seemed a vision from another century, wild-eyed horses pounding headlong; cheering, and whooping men firing from the saddles.

The charge was a success, the last ever on horseback for a U.S. cavalry unit. But dozens of Japanese had hidden in the village and now had to be routed out. The platoon moved hut to hut, shooting through the walls as the Japanese across the river sent mortar shells over. The second and third platoons of the troop arrived and helped drive the Japanese back across the river. Troop E held the village until reinforcements arrived. Once Ramsey was relieved, he realized he had been hit in the leg.

Jaundice set in on Ramsey, and he was ordered to General Hospital No. 2 for treatment. Shortly after he left, the quartermaster confiscated the surviving 250 horses and had them butchered. There was no fodder for them, and the troops and civilians were starving. The horse meat would only last until March 15. Ramsey tried hard not to mourn the loss of the horse that had carried him through battle. It was a sad end for the animals, but to many it seemed an inevitable one. For Ramsey and others, it represented not just the end of their horses, but a move away from horse-mounted cavalry altogether. He wrote, “The cavalry was finished long ago. The army knew it; only we resisted in our pointless pride.”

The battles continued down the Bataan Peninsula, many hoping all the while for the miracle of a convoy. It would be May before Wainwright was forced to surrender to the Japanese. The initial months of the battle were helped tremendously by the efforts of the 26th Cavalry Regiment. Wainwright himself wrote, “Here was true cavalry delaying action, fit to make a man’s heart sing.”

This post my Assistant Director of Collections, Toni M. Kiser.

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags : Tags: 1941, Animals in WWII, cavalry, Pacific, Philippines, Wainwright

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Leave a Reply