70th Anniversary – The Battle of Midway

On Display through July 8, 2012, Special Exhibit — Turning Point: The Doolittle Raid, Battle of the Coral Sea, and Battle of Midway

Beginnings…

When the Empire of Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese thought that they had scored a great victory. In truth, the Japanese had sealed their fate and assured their defeat by not completing the job of destroying the Pacific Fleet. While it is true and undeniable that the Japanese did deal the Pacific Fleet a hard blow, that blow was hardly decisive. The Japanese aviators that attacked Pearl Harbor that morning left the job unfinished. While the battleships lay smoking and sinking in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor, the American aircraft carriers were either at sea ferrying aircraft to far flung Pacific bases, or back home, safe in the continental forty-eight. The failure of the Japanese to eliminate the threat of American aircraft carriers would come back to haunt them 6 months later off Midway Island.

The Japanese Plan of Attack

Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto knew that in order for Japan to have a free hand in the Pacific, what was left of the American Pacific Fleet, especially its aircraft carriers must be destroyed. Yamamoto first hatched his Midway plan in March. His plan was to lure the American aircraft carriers out of Pearl Harbor so that the Japanese carrier strike force could destroy them in one final decisive battle on the high seas. Yamamoto decided that the Japanese objective should be a place that put Hawaii in imminent danger. Surely, the Americans would come to the defense of an island that put their most precious remaining base in jeopardy. Yamamoto settled on the island of Midway as the objective of his attack.

Admiral Yamamoto devised that the Japanese carrier strike force would eliminate Midway’s island-based air power, allowing his army to invade and occupy the island rapidly. Once word of the attack on Midway reached Hawaii, the island would already have been captured and the Japanese carriers would be waiting for the American carriers to come to Midway’s rescue. In the ensuing battle, the Japanese carriers would destroy what was left of the Pacific Fleet. On May 27, 1942 the Japanese first carrier strike force, known as Kido Butai, weighed anchor at Hashirajima Harbor and set off for what they thought would be the deciding victory in their war with the United States.

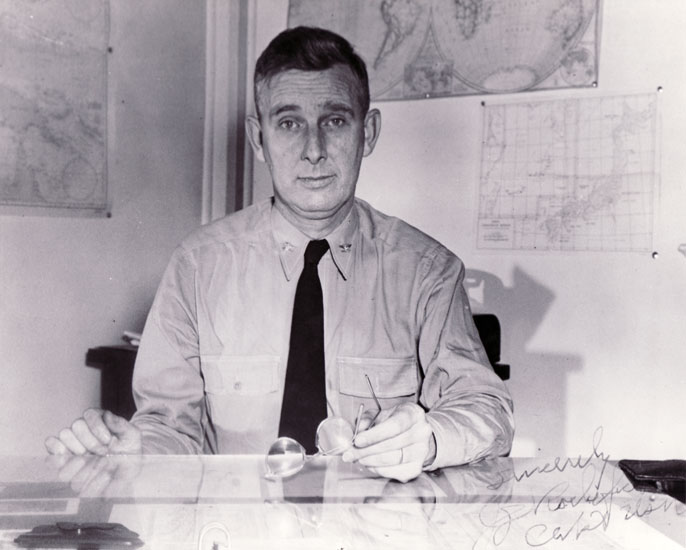

Commander Joseph Rochefort

The Secret War: American Cryptanalysts vs. JN-25

One of the most critical battles of World War II wasn’t fought on the high seas or zipping through the clouds at hundreds of miles per hour, but instead in a basement in a nondescript building at Pearl Harbor. American cryptanalysts in Hawaii (station HYPO), Corregidor (station CAST) and Melbourne, Australia (station FRUMEL) in conjunction with Dutch and British radio intelligence centers in the far east, tirelessly worked to crack the Japanese naval code – JN-25. The code was used to encrypt orders for high-level Japanese Naval operations by assigning a unique five digit code to a word. For example, the word “attack” may have a JN-25 value of “12345.” Prior to the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, naval code breakers had intercepted very few Japanese radio messages encrypted in JN-25. After 7 December 1941, however, JN-25 traffic increased exponentially. Many of the initial words decoded were routine pleasantries communicated between commands that appear in the same place on all intercepted messages, time after time. So the more messages intercepted by American code-breakers, the more pieces of the puzzle fell into place.

By the spring of 1942, Lt. Commander Joe Rochefort’s cryptanalysis section in Hawaii (station HYPO) had been experiencing some success in deciphering the Japanese code. Rochefort and his team had successfully predicted the Japanese offensive aimed at Port Moresby, New Guinea, enabling Admiral Chester Nimitz’s carriers to meet and thwart the intended Japanese invasion. It was the first time in the war the Japanese failed to achieve success in an offensive operation.

As early as April 1942, Japanese radio traffic had hinted that a major offensive was in the works, the cryptanalysts were only able to decipher fragments of radio intercepts and by no means able to read top secret Japanese operation orders verbatim, a bit of guesswork was involved in the code-breaking process. Rochefort was convinced the upcoming Japanese offensive targeted Midway Island, Nimitz trusted Rochefort’s judgment, however, Washington was unconvinced. The brass in Washington feared the Japanese may be targeting Hawaii again, or possibly even the West Coast.

It had been established by Rochefort’s team that an island that JN-25 referred to as“AF,” was the Japanese objective. To prove his hunch, Rochefort received permission from Admiral Nimitz to send a courier to Midway with instructions to have Midway radio a message to Hawaii informing them of a problem with the island’s fresh water supply in the hopes that the Japanese would intercept it. Two days later Rochefort’s team intercepted a Japanese message that said, “AF is short on water.” Rochefort’s ruse had convinced Washington that Midway Island was indeed the target of the Japanese assault. Naval cryptanalysts had also deciphered enough information to provide Admiral Nimitz with the approximate date of the attack, numbers and types of vessels and the general direction from which the Japanese would attack. This intelligence proved invaluable in leveling the playing field for the much smaller and weaker American fleet that would face the Japanese at Midway.

American preparations for battle

Admiral Chester Nimitz began to assemble his defending forces. Midway Island’s garrison of men and aircraft were built up as rapidly and as efficiently as possible. The elite 2nd Marine Raider Battalion was sent to Midway to bolster the 6th Marine Defense Battalion’s numbers and anti-aircraft artillery studded the defenses on Midway’s Sand and Eastern Islands. Midway’s most precious defense, however, was its aircraft. Nimitz pilfered every available squadron for combat aircraft and sent them to Midway. Unfortunately most of them were obsolete and flown by men who had never experienced combat. Marines flying antiquated SB2U3 Vindicators and the newer SBD Dauntless from VMSB-241 as well as VMF-221 fighter pilots driving the ancient F2A3 Brewster Buffalo were among the first to arrive. They were followed, only days before the battle, by a detachment of the Navy’s Torpedo Squadron 8, flying the brand new TBF Avenger. The Army Air Forces deployed 4 B-26 Marauders as well as a large contingent of B-17s to Midway to take part in the battle.

At sea, the size disparity between the two opposing forces was enormous. The Americans put around 50 warships in 2 task forces to sea, a pitifully small contingent to oppose the massive 200 ship armada that the Japanese were sending towards Midway. Task Force 16 centered around aircraft carriers Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8). Task Force 17 revolved around the battle scarred carrier Yorktown (CV-5), veteran of the battle of Coral Sea in May.

On May 28, 1942, Task Force 16 stood out from Pearl Harbor. The following day Task Force 17 with the carrier Yorktown, barely recovered from her Coral Sea wounds, weighed anchor and plowed through the broad blue Pacific to rendezvous with her sister ships at an aptly named spot northeast of Midway, Point Luck.

American attacks from Midway Island

At 0530 on June 4, 1942, a PBY Catalina flying boat piloted by Lieutenant Howard Addy spotted the Japanese aircraft carriers. The message was relayed immediately to Midway and in the process was picked up by the three American carriers patrolling northeast of the island.

Within the hour, the idling American aircraft stationed on Midway were sent airborne, bound for the Japanese fleet. Midway’s aircraft located the enemy force an hour or so later and attacked with disastrous results. VMSB-241, VT-8 (detached) and the 4 B-26s from Midway attacked the Japanese carrier force relentlessly, yet were slaughtered by the skillful Japanese Combat Air Patrol (CAP). The defending Japanese fighters decimated the attacking forces and reduced the attacks to harmless strikes of individual aircraft or aircraft in formations of twos or threes. No hits were scored by American aircraft on the Japanese carriers and American casualties were horrendous. Torpedo Squadron 8 (detached) attacked the Japanese fleet with 6 aircraft, only 1 managed to return. Of the 4 B-26s launched from Midway, only 2 returned, laden with wounded crewmen. The Marine dive-bombers of VMSB-241 suffered a similar fate at the hands of the Imperial Navy’s CAP and anti-aircraft artillery. Of 27 Marine aircraft launched from Midway, only 12 returned to the island.

As the first American attackers headed for the Japanese fleet, a formation of over 90 Japanese strike aircraft attacked Midway Island’s defenses. Marine Fighter Squadron 221 (VMF-221) rose to defend the island against the Japanese, however, their antiquated fighter planes were no match for the agile Zero. VMF-221 launched 24 fighters to defend Midway, only 15 survived the engagement with the Japanese aircraft. On the good side, the Japanese attackers did relatively little damage to Midway’s defenses and did virtually no damage to Midway’s vital airfield. While the American casualties were mounting, the Japanese frustrations were just beginning.

Midway Island burns following the Japanese attack on June 4, 1942.

Arm, re-arm, arm, re-arm…

After numerous American attacks, the Japanese had some discussion as to whether or not the Americans could possibly have their aircraft carriers at sea. A planned recon mission to Pearl Harbor to check for the American carriers had been scrapped, and as a result, the actual location of American carriers was unknown to the Japanese. Consequently, earlier that morning the Admiral in command of the Japanese carriers, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, ordered scout planes to be launched from his cruisers. Most had taken off on time without a hitch, but one scout did not. Because of catapult problems, scout number four from the cruiser Tone was late in launching. Therefore, the scout did not reach maximum range until several hours after the others. The previously launched Japanese scouts reported nothing in their search sectors. Scout four’s area of search was a patch of ocean Northeast of Midway, exactly where the ambushing Americans lurked.

At 0728, the aforementioned Japanese scout was astonished when he saw what appeared to be a task force of American ships. Immediately, the pilot radioed Admiral Nagumo and advised him of his discovery. Nagumo received the report at about 0745. The report read, “Sight what appears to be 10 enemy surface units, 10 degrees distance 240 miles from Midway.”

At this time, the aircraft aboard the four Japanese carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu were being rearmed with contact bombs for another strike on the airstrip on Midway Island. Nagumo was concerned over the fact that apparent land-based aircraft attacks would increase from the already sustained attacks made by Midway’s aircraft earlier that morning, and planned to strike Midway again. By the time the report of the sighting of American ships reached Nagumo, the rearming of his aircraft had already been underway for half an hour. Nagumo halted rearming orders and ordered his aircraft to be armed instead for an anti-shipping strike. This two-hour process should have been completed by approximatly1000 hours. Also at this time, Nagumo’s aircraft from the Midway strike were circling their carriers, ready to land, low on fuel. The carriers needed to recover their aircraft before commencing a launch against the recently-sighted American vessels. Nagumo decided to rearm his aircraft and recover his returning strike at the same time, thus further delaying his strike’s departure until around 1030.

The American carrier-based torpedo attacks

Word broke of the discovery of the Japanese carriers on board CV-6 at about 0534. The aircrews were briefed and told of their missions. The men that would be manning the aircraft that day aboard CV-6 were, by and large, untested aircrew. The rank and file of the scouting, bombing, and torpedo squadrons aboard most of the American carriers, had never seen combat. At 0706, Enterprise commenced launching her aircraft. Hornet followed suit. Yorktown delayed her launch until 0838. The American aircraft formed up into attack formations above their carriers, all the time burning precious fuel, and once in formation headed out towards the last known location of the Imperial Fleet.

As the American carrier aircraft lumbered towards their destiny, their formations began to break up. The inexperienced American pilots from CV-6 and CV-8 were not apt at maintaining a coordinated attack. The torpedo aircraft of Torpedo Squadrons 6 (VT-6) and 8 (VT-8) separated from their dive-bomber cohorts and, more ominously, their fighter escorts. At 0920, the first American carrier-borne strike of the battle took place.VT-8 from the carrier Hornet attacked the Japanese carrier Soryu with disastrous results. As the slow, lumbering, antiquated TBD “Devastator” torpedo bombers approached the Japanese fleet, they came under murderous attack from enemy CAP (Combat Air Patrol). With no American fighters to help repel the attackers, the results were already written on the wall before the first torpedo run was set up. Every single one of VT-8s aircraft was shot down with the loss of all hands, the exception being Ensign George Gay. Shortly after, at 0940, VT-6 from Enterprise set up their run on the carrier Kaga. The results were pathetically similar. VT-6 braved the enemy CAP and desperately called for fighter assistance but to no avail. Only two of VT-6’s TBDs escaped the onslaught and were able to return to the American fleet. Once again, the Americans had made a valorous attack, but had been destroyed by the Japanese pilots. An eerie quiet hung around the carriers of Kido Butai for the next few minutes as the CAP Zero fighters hugged the waves and searched for more torpedo bombers to shoot down. The normal operating altitude of Japanese CAP was about 12,000 feet, a perfect altitude to intercept enemy dive-bombers and fighters. However, at this juncture the CAP of Kido Butai were well below that height, having just repelled an American torpedo attack.

McCluskey’s Decision

High above the melee that was occurring below and far ahead, two squadrons of the United States Navy’s dive-bombers, the Douglas SBD “Dauntless,” crept along heading towards what was assumed to be the location of the Japanese fleet. These two squadrons, Bombing Squadron 6 (VB-6) and Scouting Squadron 6 (VS-6) were from the carrier Enterprise. A former fighter pilot, Commander C. Wade McCluskey, led the “Big E’s” strike. McCluskey had only recently been appointed as CV-6’s Air Group Commander, and had had very little time to get used to flying his new mount, the SBD. Consequently, McCluskey drove the Dauntless like a fighter, throttle to the firewall, all the time eating up precious fuel. As it was, the strike assigned to the SBDs from CV-6 put them at their absolute maximum range. Many of the young, inexperienced pilots did the math and knew that they would probably run out of fuel before they reached home, if they reached home.

As the fuel gauges ran low, so did McCluskey’s patience. He was sure that the Japanese were out there. At 0930, he approached and then passed the suspected area of interception. McCluskey was faced with what was, at that point, the most critical decision made by a field commander of the United States military. Should he turn his aircraft around and head home empty-handed to save his pilots or should he continue on and see if he can find the enemy? The weight of the attack was on McCluskey’s shoulders and he made the decision that would eventually win the battle. Wade McCluskey, without any orders from his superiors decided to risk it and keep searching. “At 0935 he turned to 315 degrees to fly up the approach course of the enemy. He intended to follow this reciprocal route for some fifty miles until 1000.”After that point, he would reluctantly turn for home and get his men back to their ship. At 0955 just five minutes before he was supposed to turn back for home, McCluskey spotted the wake of one lone enemy ship. The Japanese destroyer Arashi was moving at flank speed, her bow pointing like an arrow towards McCluskey’s target. Wisely, McCluskey elected to fly the destroyer’s course. Just five short minutes later at 1000 hours he was rewarded with the sight of many wakes dead ahead through the scattered clouds, some thirty-five miles ahead. At 1002, he radioed Raymond Spruance, the commanding officer aboard Enterprise, “This is McCluskey. Have sighted the enemy.”

The Morning Raid 1019-1024

From 20,000 feet, the empty natural yellow wood decks of the Japanese carriers stood out on the broad blue sea. The giant red “meatballs” painted on the forward flight deck were even more conspicuous. What astounded the American SBD pilots was the lack of any CAP. The SBD gunners in the rear cockpit were on their toes even more than normal expecting to fly into a hornet’s nest. Once they spotted the enemy carriers, there should have been an enemy CAP to meet them. Yet, no enemy fighters appeared. Everyone wondered where the CAP was, yet no one wanted to stick around to find out.

At 1019, Wade McCluskey radioed his squadron commanders, Earl Gallaher and Dick Best of VS-6 and VB-6 respectively instructing Best to hit the carrier to port and at the same moment he ordered Gallaher to attack the target to starboard. Deciding to head the starboard strike himself, McCluskey added, “Earl, follow me.”

At 1020, the SBDs of VS-6 and VB-6 pushed over from 20,000 feet and went into their near vertical dives. McCluskey aimed first and missed at Kaga, his two wingmen followed suit with the same results. Yet again the Americans had failed to score a hit, however, that was about to change. Earl Gallaher of VS-6 hurtled downward at 350 miles per hour and pulled the bomb release on his SBD. The aircraft lurched and he executed a screaming pull out at wave top height. The 500-pound armor piercing bomb that he released plunged through Kaga’s flight deck before coming to rest amongst the just recently rearmed and refueled Japanese aircraft in the hangar deck. The 500 pounder went off and produced an enormous fuel-fired explosion in Kaga. VS-6 pilots pounded the Japanese carrier, inflicting fatal damage within a span of two minutes. The carrier Akagi was attacked by a flight of three SBDs including VB-6’s squadron commander Dick Best. An incredibly lucky hit was scored on Akagi by Best as his bomb too exploded amongst the rearmed and refueled aircraft in the hangar deck. Akagi suffered only one hit, the one scored by Best. That one hit and the ammunition-fueled fires that resulted, were enough to doom the flagship of Kido Butai. Simultaneously, just a short distance away, Yorktown’s Bombing Squadron 3 (VB-3) and Torpedo Squadron 3 (VT-3) attacked Soryu and Hiryu respectively with VB-3 scoring fatal hits on Soryu within minutes of VS-6 and VB-6’s attacks.

As the victorious SBD pilots pulled away from the fleet, they described the event, Clarence Dickinson relates, “The target was utterly satisfying, the squadron’s dive was perfect. This was the absolute. I felt that anything after this would be anti-climactic.” With that the survivors from the American SBDs pulled together and headed for home. In an astonishing four minutes, from 1020 to 1024, the pilots of three American SBD “Dauntless” dive-bomber squadrons reversed the tide of the Pacific War.

Afternoon attack on Yorktown and Hiryu

After the devastating American SBD attack on the Japanese fleet had ended, the sole remaining Japanese carrier Hiryu launched an attack of her own towards the reported target of an American aircraft carrier. Following Yorktown’s retiring VB-3s back home, the Japanese strike soon overtook the SBDs and passed them, beating them to their carrier. At 1200, the Japanese attacked Yorktown and scored several hits with bombs. As a result, CV-5 stopped dead in the water, but would soon get her steam back and continue the fight. At 1320, Hiryu launched her second attack. his one proved deadly to “The Mighty Y.” In the ensuing attack, CV-5 absorbed two torpedoes, she finally stopped dead for the last time and began to list badly to port. At 1455, Yorktown was abandoned.

Shortly thereafter, Admiral Ray Spruance on board Enterprise received the sighting report containing the whereabouts of Hiryu and subsequently launched an attack. The attack force was made up of the remaining aircraft from VS-6, VB-6 and VB-3. Hornet also launched her remaining SBDs in the attack against the last surviving Japanese fleet carrier at Midway. The SBDs attack on Hiryu was identical to the morning strikes as the Americans scored repeated hits on Hiryu and at 1705 left her a flaming wreck like her sisters before her. The American raid on Hiryu was a resounding success as casualties were relatively light. Only 2 SBDs, from the 25 launched, failed to return to Enterprise.

USS Yorktown stops dead in the water after receiving bomb hits during a Japanese air attack at the Battle of Midway.

The battle concludes…

The battle continued on 5 June, but proved to be anti-climactic to say the least. A lone Japanese ship was spotted, the destroyer Tanikaze. Thirty-two American SBDs attacked, but not a single hit was scored. The defiant little destroyer shot down several attacking SBDs in the melee.

On 6 June, SBDs from CV-6 and CV-8 attacked the Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma and utterly destroyed the ship. Mikuma had collided with her sister Mogami on the 4 June and was limping back to Japan when the marauding SBDs found her and left her a floating derelict. The attack on Mikuma and Mogami was the last air attack of the Battle of Midway.

Later that day, the Japanese submarine I-168 spotted the badly listing carrier Yorktown and fired a spread of torpedoes at her. The workers aboard CV-5 attempting to save her spotted the incoming missiles and dove for cover. I-168 fired three torpedoes, one hit and sunk the destroyer Hammann (DD-412). The other two torpedoes slammed against CV-5’s hull and ripped it open. Still, despite the tremendous damage, Yorktown remained afloat. On 7 June, she finally succumbed to her wounds. “At 0443 she lay on her port side, revealing a huge hole in her starboard bilge the result of yesterday’s submarine attack. The end was near and at 0454 all ships half masted their colors and came to attention… At 0501, well down at the stern Yorktown slowly sank from sight.” With that the Battle of Midway was over.

Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma smoking and sinking.

Conclusions

The Battle of Midway was a resounding success for the United States Navy. In just four days the Pacific Fleet had reversed the tide of war against the Japanese. The victory not only crippled the Japanese Imperial Navy by destroying four of its front line fleet carriers and reducing its striking power, it deprived them of over 4,800 irreplaceable men, among them some of its finest aviators. By destroying the enemy at Midway, Nimitz’s forces bought themselves priceless amounts of time. The time bought and paid for with the blood of 307 U.S. servicemen allowed the United States to launch its first ground offensive in the Pacific, which took place on August 7, 1942, with the landings at Guadalcanal.

Due to the defeat at Midway, the Japanese Navy would not venture on the offensive again until the Guadalcanal Campaign in August of 1942. Even then, the Imperial Navy was a shell of its former self. Victories at Savo Island in August and Santa Cruz in October were only compounded by the carrier losses at Eastern Solomons in August and the loss of Guadalcanal altogether. What was started at the Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942, was finally concluded in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, with the unconditional surrender of Japan.

Post by Seth Paridon, Manager of Research Services for The National WWII Museum.

Watch oral histories and see artifacts and images from the Museum’s Collection.

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags : Tags: 1942, Midway, Pacific, Turning Point

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Leave a Reply