Posts Tagged ‘Football in WWII’

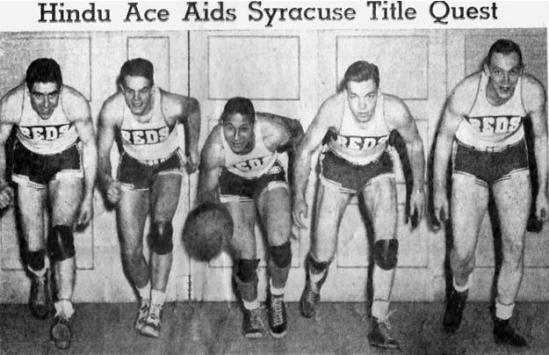

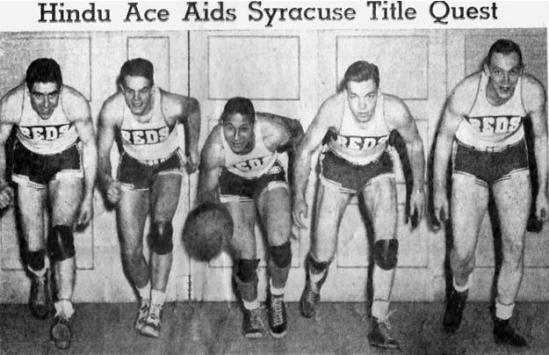

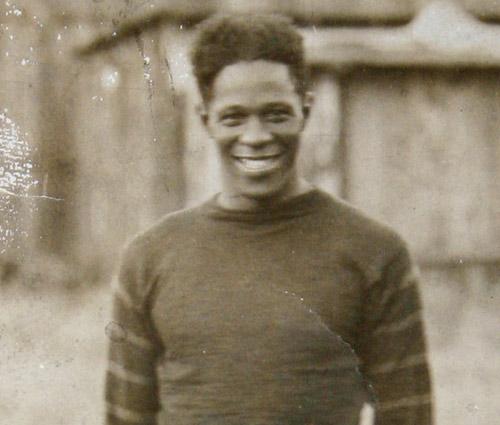

Syracuse University basketball and football star, Wilmeth Sidat-Singh (center), was often referred to in the press as Hindu (a term at the time used to describe someone of Indian heritage). Singh, however, was born to African American parents. After his father died, his mother remarried a man from the West Indies who adopted young Wilmeth Webb.

While he never claimed to be something he wasn’t (and often tried to clear up the error in the press to no avail), this popular misconception allowed Sidat-Singh to travel and play with teammates to a schools that did not allow African Americans to compete in sports. An article finally explaining his true ethnicity cost him the opportunity to play in a game soon after in Maryland. The star halfback, known as the Syracuse Walking Dream, sat on the sidelines as the Orangemen lost the game, powerless to assist his teammates.

After college, there were no opportunities for an African American in professional sports, so Sidat-Singh played for two barnstorming teams, the Syracuse Reds and the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1943, he answered the call to serve his country and became a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen. On May 9, 1943, his engine failed during a training mission over Lake Huron and Sidat-Singh drowned. He was 25 years old.

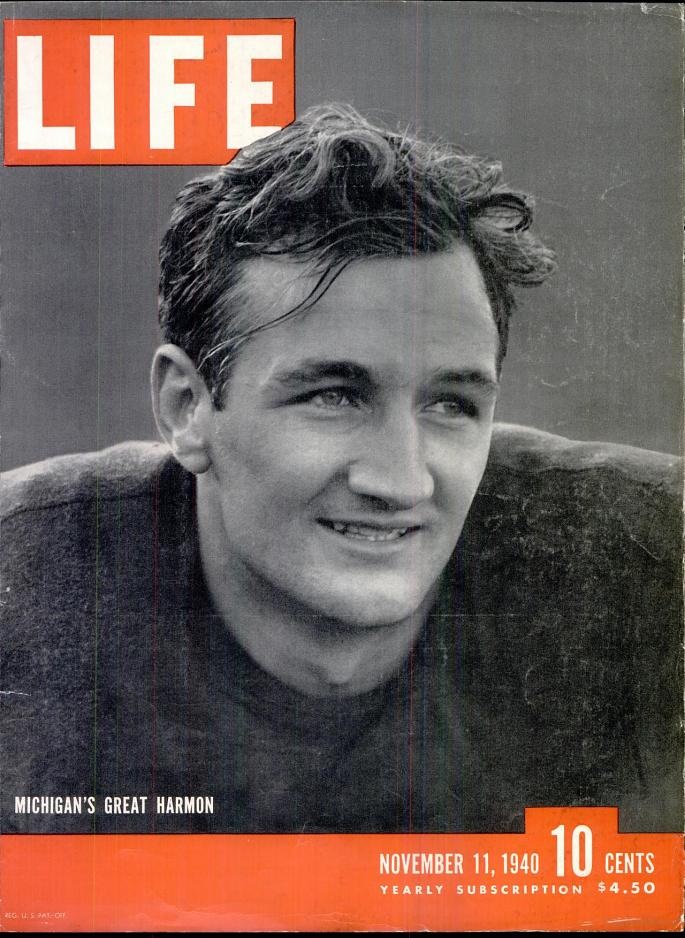

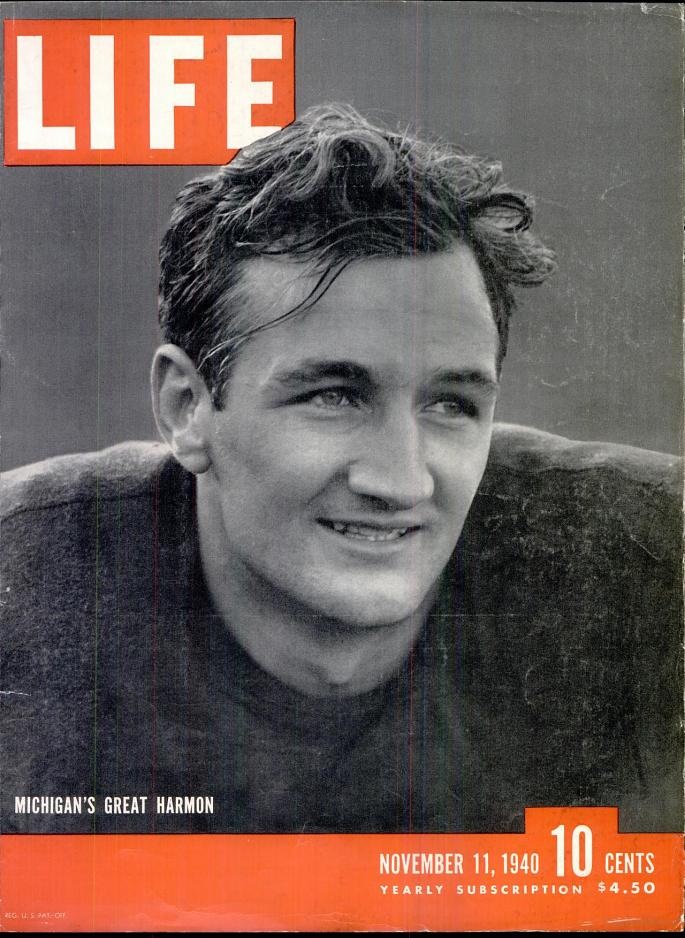

April 10, 1943 – Former all-America tailback at the University of Michigan and Heisman Trophy winner, Tom Harmon (US Army Air Corps) was the only member of his crew to survive a crash over Suriname due to weather conditions.

More About Tom Harmon –

Excerpt from Tom Harmon’s Obituary, The New York Times, March 17, 1990

Twice during World War II he was reported missing in action. In April 1943 he crashed into the jungles of Dutch Guiana, which is now Suriname, and marched alone through swamps and rain forests four days before he was rescued by natives.

Later that year, he bailed out of his P-38 fighter plane over China when it was shot down in an air fight. When he reached the ground, there were bullet holes in his parachute, and he pretended he was dead to discourage the enemy pilots from further attacks. He was smuggled back through Japanese-held territory to an American base by friendly Chinese bands.

When Harmon married Elyse Knox, an actress, on Aug. 26, 1944, the bride used the white silk and white cords from his parachute in her wedding gown.

After the war, Harmon received a $7,000 tax bill for earnings on the movie he had made in 1941. He accepted a $20,000-a-year offer from the Los Angeles Rams football team and performed for them through two unimpressive seasons. Wartime leg injuries robbed him of his former speed and power.

After ending his playing career, Harmon spent the rest of his life as a sports broadcaster in radio and television, based mainly in Los Angeles. In 1974, he joined the Hughes Television Network as a sports director, hired to coordinate sports programming and to serve as a commentator at major golf tournaments.

”Sports broadcasting was the only job I ever wanted,” he said. ”It was the thing I loved because it put me among people I knew and wanted to be with.”

The Michigan sports blog MGOBLOG also credits Harmon as the man who “made NCIS possible by fathering son, Mark.”

Tom Harmon (top row, center) and crew at Atkinson Field

NFL Teams Take Drastic Measures Due to Manpower Shortage

As World War II siphoned the ranks of the NFL, a severe manpower shortage emerged. In 1943, the shortage was so severe the league changed its rules to allow for free substitution. The player shortage forced the Cleveland Rams to suspend play for the 1943 season, while the Pittsburg Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles agreed to merge. In 1944, the Steelers merged with the Chicago Cardinals.

Program for the October 9, 1943 game between the Eagles-Steelers and the Giants in Philadelphia, PA.

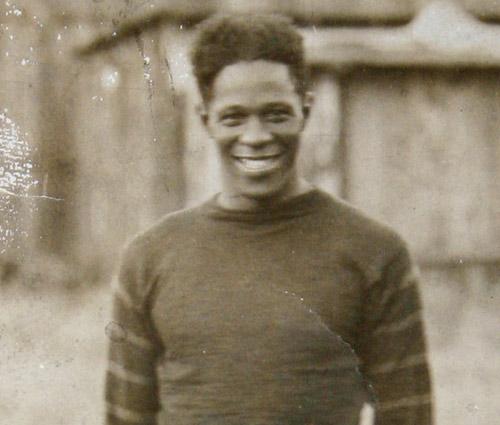

Fritz Pollard, an All-America halfback with Brown University, led his team to the Rose Bowl following the 1915 season. Pollard went on to play in the NFL (one of 2 African American players in the league when it was founded in 1920) and become pro football's first African American head coach.

Although the end of WWII brought a new sense of social consciousness, segregation and discrimination remained in much of the United States. However, employment opportunities did begin to open up for African American in some sectors. Sports was a visible example. In 1946, pro football reintegrated, ending its 12-year “color barrier.”

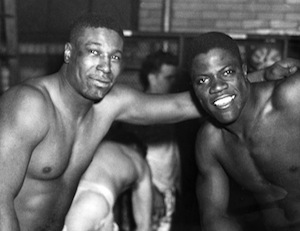

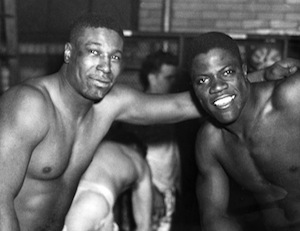

Marion Motley and Bill Willis celebrate after helping the Cleveland Browns win the 1946 All-American Football Conference Championship.

Two African Americans, Frederick “Fritz” Pollard and Robert “Rube” Marshall, played in the NFL when the league was founded in 1920. During the next 14 seasons, only 13 African Americans total would appear on league rosters.

In 1946, the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams and the Cleveland Browns of the rival All-America Football Conference each signed two black players. The Rams signed former UCLA halfback, Kenny Washington and end, Woody Strode. The Browns signed Nevada fullback, Marion Motley and Ohio State middle guard, Bill Willis. Washington and Strode played semipro football prior to signing with the Rams and age and injury limited their NFL careers. Motley and Willis went on to become superstars and were eventually elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

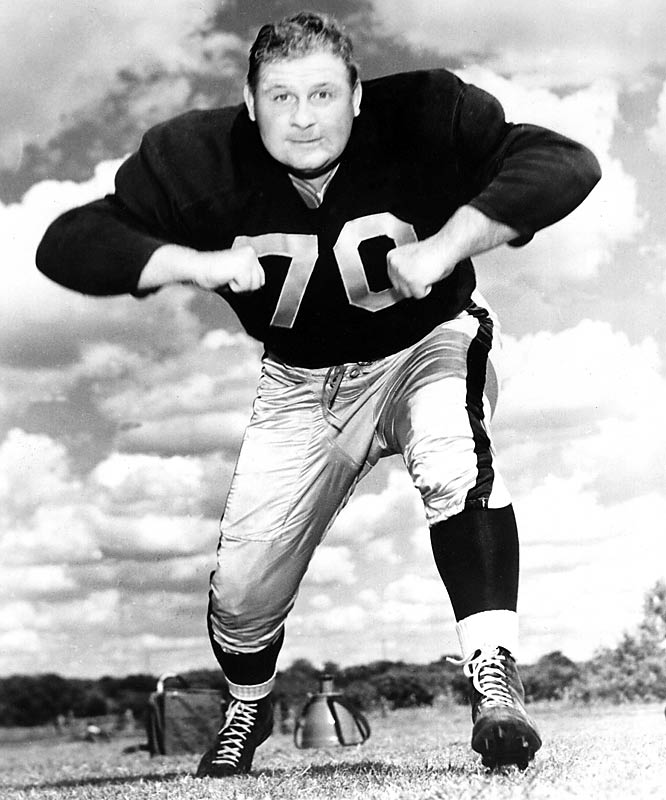

Currently on display at The National WWII Museum, Donovan’s Number 70 Colts jersey and Marine Corps jacket honor the life of one of the oldest living professional football players.

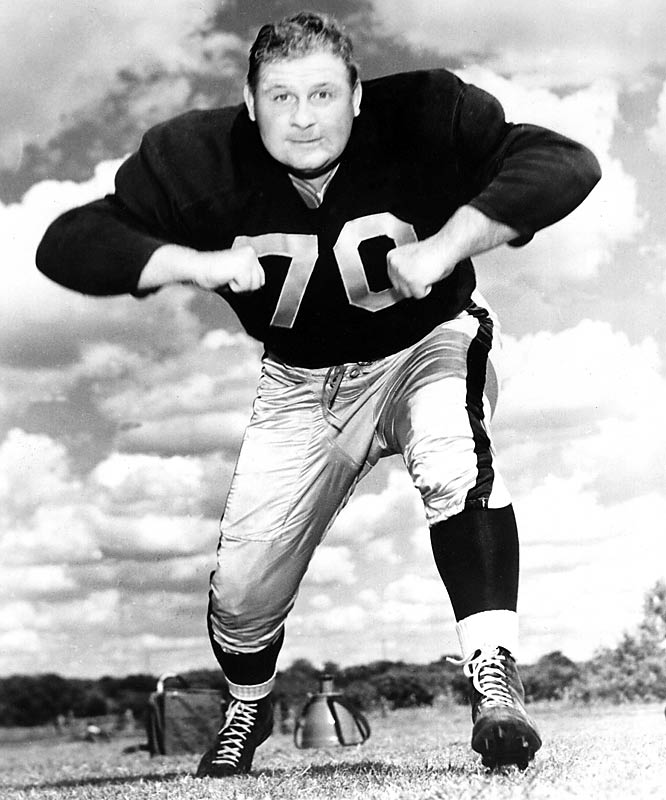

In 1943, Hall of Fame defensive tackle, Art Donovan, put his college and pro football careers on hold to serve in World War II. Enrolled in Notre Dame, Donovan postponed college, opting instead to enlist in the US Marine Corps. He was later assigned as part of Marine naval detachment to a gunnery crew on the aircraft carrier USS San Jacinto, and first saw action during the Marianas Islands campaign. Following service on the San Jacinto, Donovan volunteered to serve as a machine gunner and saw action on Okinawa, After Okinawa, he was reassigned to the 3rd Marine Division on Guam.

After the war, Donovan attended his final three years at Boston College, starting as a two-way tackle the entire time. He was a 26-year old rookie when he joined the Baltimore Colts in 1950. The Colts folded after one season, and Art moved to the New York Yanks in 1951, then played for the Dallas Texans in 1952.

In 1953, the well-traveled Donovan returned to Baltimore to play for the new Colts franchise and, as the Colts developed into a championship team, Donovan developed into one of the best defensive tackles in league history.

The 6-foot-3, 265-pound defensive tackle was smart and quick, able both to rush the passer and to move laterally to stop running plays. Donovan was also one of the most popular players in the league. He was an All-NFL selection in 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, and 1958. In addition, he played in five straight Pro Bowls.

The Baltimore Colts’ great title teams of 1958 and 1959 featured a terrific defensive line, with future Hall of Fame defensive end Gino Marchetti, Don Joyce, “Big Daddy” Lipscomb, and Donovan, who by then had become the complete player. He was equally adept at rushing the passer, reading keys, closing off the middle, and splitting double team blocks. He had the reputation of being almost impossible to trap.

As great of a contributor as he was on the field, many feel he was just as valuable to the Colts as a morale builder, with his sharp wit and contagious laughter. The Colts retired his jersey, Number 70, in 1962 when he left professional football after 12 seasons in the NFL. In 1962, he also became the first Colts player elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

On set of a video piece for the 2011 Super Bowl, Donovan was flanked by active-duty Marines. After spending most of the shoot making his uniformed co-stars laugh in a serious moment he told the Marines, ‘‘People think the [NFL] players and owners making all that money are heroes. You are my heroes — thank you.”

Plan your visit to see Gridiron Glory before it closes at The National WWII Museum on May 5, 2013.

Art Donovan

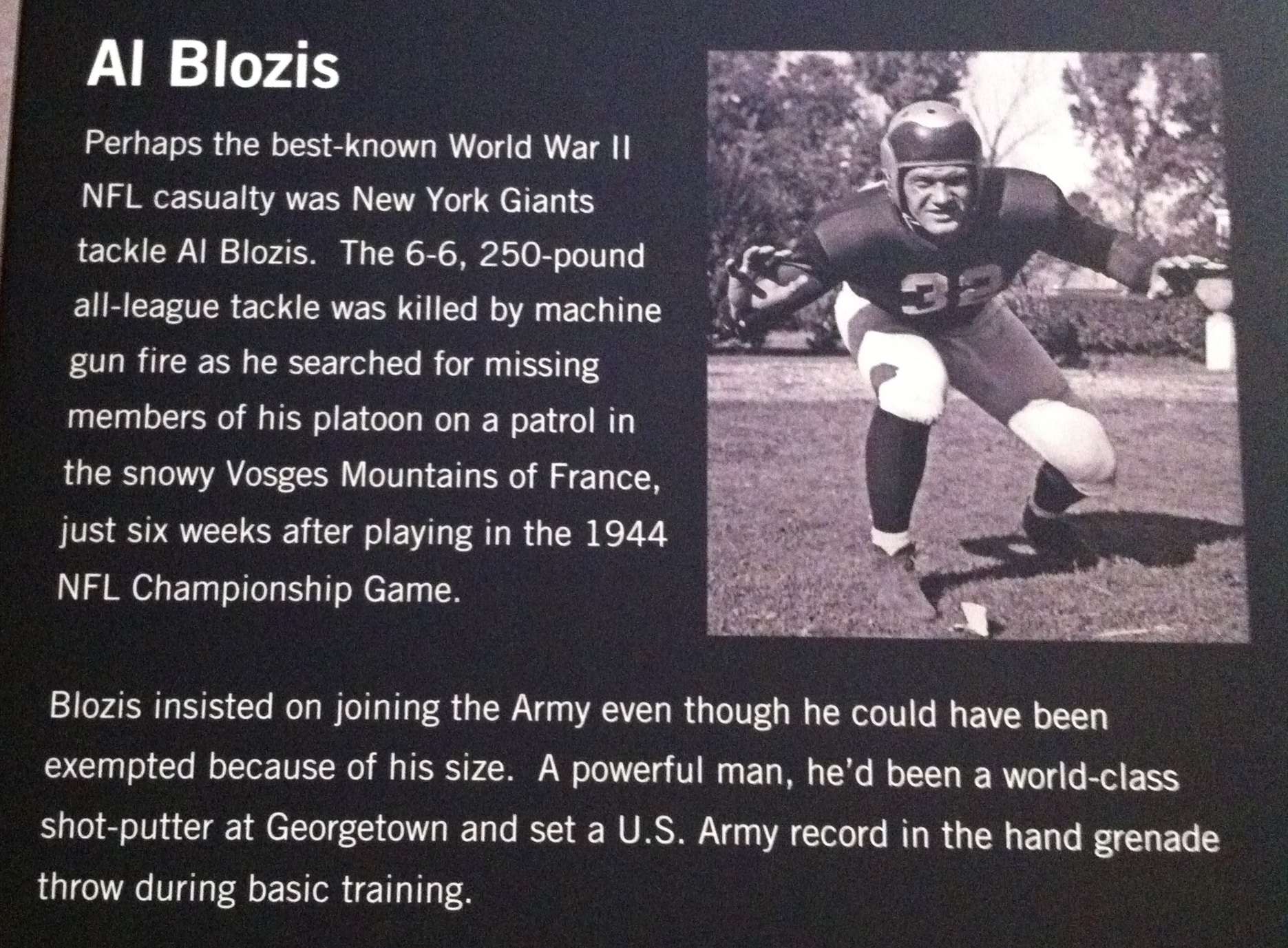

World War II claimed the lives of 23 NFL men – 21 active or former players, an ex-head coach and a team executive. Listed below are the NFL personnel killed during the war.

Cpl. Mike Basca (HB, Philadelphia, 1941) – Killed in France 1944

Lt. Charlie Behan (E, Detroit, 1942) – Killed on Okinawa, 1945

Maj. Keith Birlem (E, Cardinals-Washington, 1939) – Killed trying to land a combat-damaged bomber in England, 1943

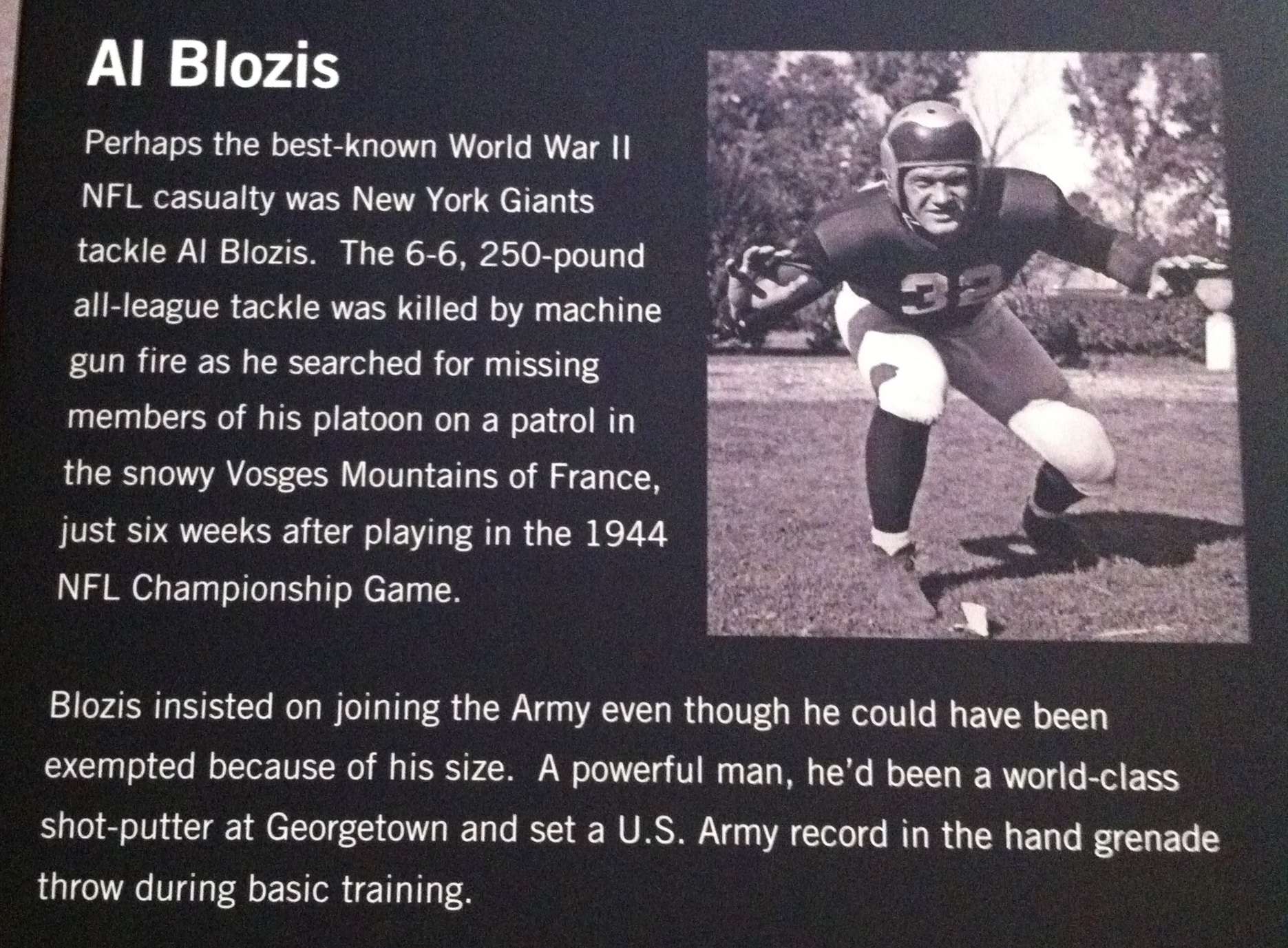

Lt. Al Blozis (T, Giants, 1942-1944) – Killed in France

Lt. Chuck Braidwood (e, Portsmouth-Cleveland-Cardinals-Cinncinati, 1930-1933) – Member of the Red Cross. Killed in the South Pacific, 1944

Lt. Young Bussey (QB, Bears, 1940-1941) – Killed in the Philippines landing assault, 1944

Lt. Jack Chevigney (Coach, Cardinals, 1932) – Killed on Iwo Jima, 1945

Capt. Ed Doyle (E, Frankford-Pottsville, 1924-1925) – Killed during North Africa invasion, 1942

Lt. Col. Grasst Hinton (B, Staten Island, 1932) – Killed in a plane crash in the East Indies, 1944

Capt. Smiley Johnson (G, Green Bay, 1940-1941) – Killed on Iwo Jima, 1945

Lt. Eddie Kahn (G, Boston/Washington, 1935-1937) – Died from wounds suffered during Leyte invasion, 1945

Sgt Alex Ketzko (T, Detroit, 1943) – Killed in France, 1944

Capt. Lee Kizzire (FB, Detroit, 1937) – Shot down near New Guinea, 1943

Lt. Jack Lummus (E, Giants, 1941) – Killed on Iwo Jima, 1945

Bob Mackert (T, Rochester Jeffersons, 1925)

Frank Maher (B, Pittsburgh-Cleveland Rams, 1941)

Pvt. Jim Mooney (E-G-FB, Newark-Brooklyn-Cincinnati-St. Louis-Cardinals, 1930-1937) – Killed by sniper in France, 1944

Lt. John O’Keefe (Front office, Philadelphia) – Killed flying a patrol mission in Panama Canal Zone

Chief Spec. Gus Sonnenberg (B, Buffalo-Columbus-Detroit-Providence, 1923-1928, 1930) – Died of war-related illness at Bethesda Naval Hospital, 1944

Lt. Len Supulski (E, Philadelphia, 1942) – Killed in plane crash in Nebraska, 1944

Lt. Don Wemple (E, Brooklyn, 1941) – Killed in a plane crash in India, 1944

Lt. Chet Wetterlund (HB, Cardinals-Detroit, 1942) – Killed in plane crash off New Jersey coast, 1944

Capt. Waddy Young (E, Brooklyn, 1939-1940) – Killed in a plane crash following first B-29 raid on Tokyo, 1945

All information courtesy of the Pro-Football Hall of Fame.

On display through May 5, Gridiron Glory: The Best of the Pro Football Hall of Fame presents a panoramic view of the story of professional football — from its humble beginnings in the late 19th century to the cultural phenomenon it is today — and brings together an extraordinary collection of artifacts, while creating an unforgettable interactive experience. The Hall of Fame has partnered with NFL Films in creating the audio and video for this exhibit.

The exhibition — a cornerstone event in the multi-year celebration of the Hall of Fame’s 50th anniversary — is the most extensive and comprehensive exhibition featuring America’s most popular sport ever to tour.

In addition to an exclusive display of WWII-era NFL artifacts, this exhibition of Gridiron Glory also includes historic items related to the New Orleans Saints.