Posts Tagged ‘Navy’

March 27, 2013, (or March 26 if you are going by Hawaiian time) marks the 70th anniversary of one of World War II’s forgotten naval clashes, the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. Although a minor engagement in which no ships were sunk, the battle off the Komandorskis was a significant strategic victory for the US Navy as it prevented desperately needed supplies from reaching Japanese forces in the Aleutian Islands.

The Battle of the Komandorski Islands came about as a result of an intercepted Japanese radio message notifying Japanese forces on Attu that supplies were en route from Japan. Once the message was decrypted in Hawaii, Rear Admiral Charles McMorris was ordered to intercept and destroy the Japanese convoy with one heavy cruiser, one light cruiser and four destroyers.

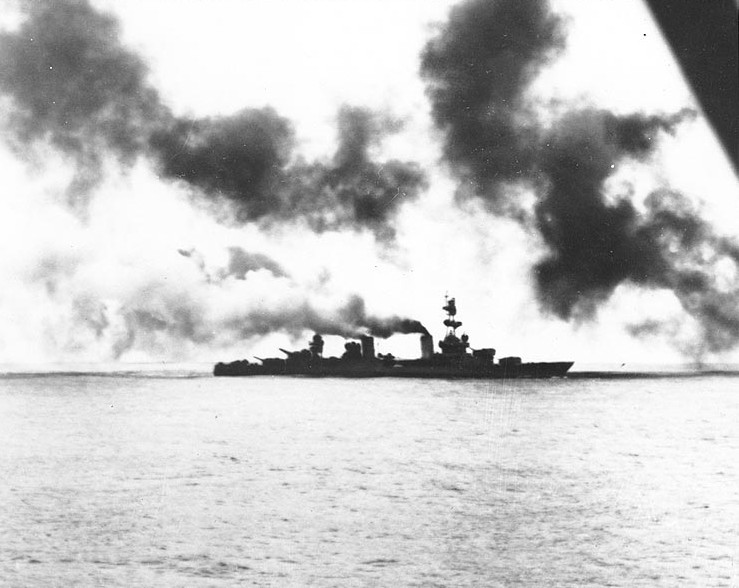

What should have been an easy victory was complicated by the fact that the Japanese convoy was escorted by two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and four destroyers. So, when the two forces collided off the Soviet-controlled Komandorski Islands early on the morning of 27 March 1943, McMorris’s ships found themselves in a stand-up fight with a superior Japanese force. What followed was a running gun battle that lasted over six hours. Both sides suffered damage, with the USS Salt Lake City being hit by six 8” shells. The Japanese cruiser Nachi was also heavily hit during the battle. Ultimately, around noon on the 27th, the Japanese convoy turned back.

USS Salt Lake City, shown during the Battle of the Komandorski Islands, 27 March 1943

Taken at Mare Island, this photo highlights the hits suffered by the Salt Lake City off the Komandorskis

No ships were lost on either side, and less than sixty casualties were suffered on both sides, but the damage done to the Japanese off the Komandorskis was much greater than the sum of damaged ships and wounded men. The battle effectively sealed off the northern supply route to the Aleutian Islands. After March 1943, Japanese forces in the Aleutians were only supplied by submarines, which were incapable of providing the amount of material needed for the Japanese force to hang on. Although nearly forgotten today, the Battle of the Komandorski Islands had a decisive impact on America’s victory in the Aleutian Islands.

Posted by Curator Eric Rivet

Today marks the 70th anniversary of the opening shots of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, a series of vicious battles between the US and Japan that helped to bring about the end of the Guadalcanal campaign. The battles were triggered by a major Japanese attempt to eliminate the US beachhead surrounding Henderson Field. A powerful Japanese surface force composed of two battleships, one cruiser and eleven destroyers sailed for Guadalcanal on 12 November with the intention of shelling Henderson Field into oblivion. The Japanese force was soon spotted by aerial reconnaissance and Allied coast watchers.

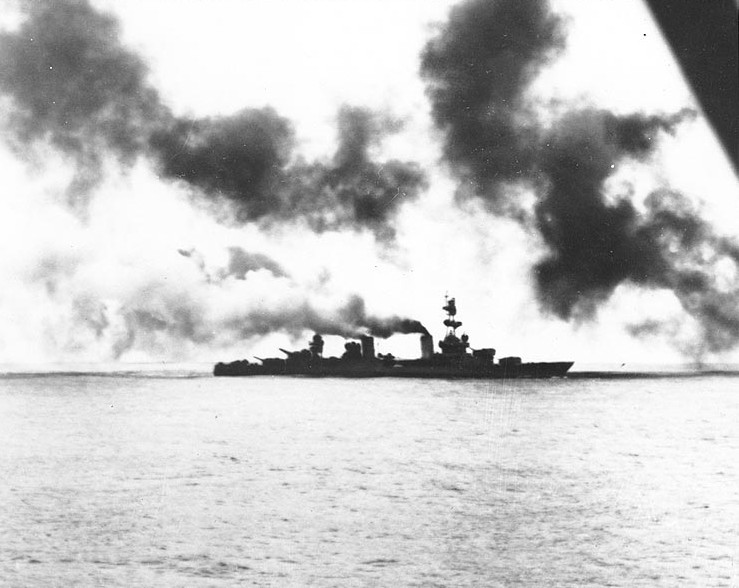

Meanwhile, a large American resupply convoy arrived at Guadalcanal on the 11th. Their unloading efforts were quickened once word of the approaching Japanese force reached Guadalcanal on the 12th. As the transports and their escorting cruisers and destroyers attempted to clear the area, they came under attack by a large formation of Japanese G4M “Betty” bombers. Most of the attackers were shot down by concentrated anti-aircraft fire and Wildcats from Henderson Field, but one “Betty,” probably with a dead pilot, crashed into USS San Francisco’s aft machine gun platform and then fell overboard into the sea.

USS San Francisco (center) burns after being struck by a “Betty” bomber.

Fifteen men were killed in the crash, including all twelve men on the machine gun platform. Each of those men, who kept firing at the plane even as it crashed into them, were honored by having a destroyer escort named after them. One of those ships, the USS Slater DE-766, is preserved today as a floating museum in Albany, New York.

USS Slater DE-766, named in honor of Seaman Frank Slater, killed aboard USS San Francisco 12 November 1942.

After the transports cleared the area, the escorting cruisers and destroyers were ordered to turn back and attempt to drive off the approaching Japanese surface force. Although the American ships were vastly outgunned, they were the only US warships available at the time. As daylight faded on the evening of 12 November 1942, the US and Japanese forces steamed towards each other. They would soon meet in one of the shortest and bloodiest naval battles of the Pacific War.

Posted by Curator Eric Rivet

Rear Admiral Norman Scott, victor of the Battle of Cape Esperance

Today marks the 70th anniversary of the start of the Battle of Cape Esperance, the second major naval battle to occur at night during the Guadalcanal campaign. Although strategically unimportant, the American victory at Cape Esperance proved to be a much needed morale boost for the US Navy.

Prior to the Battle of Cape Esperance, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the uncontested master of the water around Guadalcanal at night. Japanese ships used the cover of darkness to bring supplies and reinforcements to the men struggling to recapture Henderson Field from American soldiers and marines. These resupply runs, known as the “Tokyo Express” frequently included bombardments of Henderson Field by Japanese cruisers and destroyers.

After two months of uninterrupted trips to Guadalcanal, the Japanese had grown complacent. And so it was that on the night of 11-12 October 1942, a Japanese bombardment force of three heavy cruisers and two destroyers was ambushed by an American task force under Rear Admiral Norman Scott.

Scott’s force of four cruisers and five destroyers first spotted the Japanese warships at 11:43 p.m. on the 11th. The Japanese commander mistakenly believed that the unidentified ships were a Japanese resupply convoy, so he ordered his ships to turn on their recognition lights. Immediately after the lights went on, the Japanese ships were deluged by American shells. What followed was nearly forty minutes of chaos as both sides fired at shell flashes and launched torpedoes in the darkness.

USS Boise’s scoreboard, which claims six Japanese ships sunk at Cape Esperance. In reality, only five Japanese ships fought at Cape Esperance, and only two of those were sunk.

The Japanese cruiser Furutaka and the destroyer Fubuki were sunk, and the cruisers Aoba and Kinugasa were damaged during the battle. On the American side, the USS Duncan DD-485 was sunk, and the USS USS Salt Lake City CA-25, USS Boise CL-47, and USS Farenholt DD-491 were all damaged.

Tactically, the Battle of Cape Esperance was an American victory. The Japanese bombardment force was turned back after suffering major damage. Strategically though, Cape Esperance was a minor victory at best. Although Scott’s force bought Henderson Field one night’s reprieve from bombardment, he did not stop the Tokyo Express. In fact, a Japanese reinforcement convoy landed troops and supplies on Guadalcanal while the battle raged. However, the Battle of Cape Esperance provided a critical morale boost for the US Navy when it was desperately needed. Norman Scott and the ships under his command put the first dent in the Imperial Navy’s seemingly impenetrable armor 70 years ago today.

Posted by Curator Eric Rivet

The Wasp gets hit hard, 15 September 1942. Gift of Lionel Taylor, 2010.396.005

The USS Wasp (CV-7) was laid down on 1 April 1936, and commissioned on 25 April 1940. The [exceptionally small] aircraft carrier was built according to proportions agreed upon at the Washington Naval Conference in 1922. For the Wasp, this meant displacing no more than 15,000 tons. To build such a light aircraft carrier meant doing without much armor at all, which certainly contributed to the ship’s demise on this day 70 years ago, 15 September 1942.

Before America declared war, the Wasp was one of several ships that participated in the transport of US aircraft to Iceland in late summer 1941. After months spent training and patrolling the Atlantic—and an American declaration of war—Wasp was sent once again to ferry aircraft on behalf of the British RAF for actions at Malta in April 1942, and a return trip a month later to replace heavy aircraft losses in the first go-round.

After losing two carriers in naval combat (Lexington at Coral Sea and Yorktown at Midway), the Wasp was suddenly in high demand in the Pacific. With the American invasion of Guadalcanal in the works by July 1942, the Wasp was assigned to Admiral Fletcher’s force. Beginning in the early hours of 7 August 1942, Wasp’s Avengers, SBDs, and Wildcats hit several Japanese positions throughout the Guadalcanal islands, taking out 24 enemy aircraft at the cost of 4 of their own.

On 15 September 1942, Wasp along with the only other carrier available in the Pacific, the Hornet, was on escort duty ensuring the landing of 7th Marines on Guadalcanal proper. She was struck by several torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-19. Being as Wasp was lightly armored due to its construction limitations, she was particularly vulnerable. On top of that, she was hit much like the battleship Arizona was at Pearl Harbor, struck near the magazine causing huge explosions from ammo and gasoline. The fires could not be fought and the order to abandon ship was given. After a successful evacuation, the Wasp soon rested on the floor of the waters off Guadalcanal. Though her aircraft in the sky at the time of the attack were able to make emergency landings elsewhere, the rest of the planes the Wasp carried were lost with the ship. Nearly 200 brave sailors lost their lives with the sinking of the Wasp, with many more wounded. Today, we remember those men.

This post by Curator Meg Roussel

Steward, Third Class Howard Madison Walker from Bowling Green, Kentucky and 78 crewmembers of the submarine USS Tang perished on October 24, 1944, when one of the subs torpedoes malfunctioned and struck her. Approximately 400,000 Americans lost their lives during WWII. Each of these heroes deserves to be remembered — their stories preserved and cherished for generations.

Steward, Third Class Howard Madison Walker from Bowling Green, Kentucky and 78 crewmembers of the submarine USS Tang perished on October 24, 1944, when one of the subs torpedoes malfunctioned and struck her. Approximately 400,000 Americans lost their lives during WWII. Each of these heroes deserves to be remembered — their stories preserved and cherished for generations.

Take a moment today to visit mymemorialday.org to see just a few of these stories which are housed in The National WWII Museum’s exhibits and collections. Look at their photos, see the things they touched and read the letters they wrote home describing the war in their own words.

With your support we can digitize even more artifacts, images and oral histories so they are available for generations to come. Our goal is to raise $40,000 before this Memorial Day — just a few weeks from today. These funds could be used to purchase software and other tools vital to this effort. With your help, we can reach this important milestone.

Visit mymemorialday.org today to learn the true purpose of Memorial Day and be sure to share it with your friends and family via email and social networks.

This Memorial Day, we remember them. We ask you to do the same.

Share this message via email.

Like it on Facebook.

Tweet it.

You can also show your support by making a donation today to help us continue preserving the stories of the Greatest Generation.

On April 2, 1942, the USS Hornet steamed out of San Francisco with sixteen B-25s secured to the flight deck. Also on board was the already legendary Lt. Col. James Doolittle and his crew. He and his all-volunteer force were on a secret, one-way mission to exact a small taste of vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor just four months earlier.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of what came to be known as the Doolittle Raid and the succeeding actions that turned the tide of the Pacific war, culminating with the battle of Midway in June 1942,The National WWII Museum presents the special exhibit Turning Point: The Doolittle Raid, Battle of the Coral Sea, and Battle of Midway. On display April 18 – July 8, 2012, Turning Point tells the David and Goliath story of how a woefully out-gunned and outnumbered task force of aircraft carriers, diligent intelligence work and handful of intrepid aviators halted Japanese expansion in the Pacific.

Get a sneak peek at images, artifacts and exclusive oral histories that will be featured in the exhibit at turningpoint1942.org. The site also includes classroom resources for teachers and information on how to bring Turning Point to your town with the new, affordable Green Traveling Exhibit option.

Find out more.

On March 1, 1942, Captain Albert Harold Rooks, along with the majority of the crew of the USS Houston perished in the line of duty. The mere 368 survivors of the crew of more than 1,000 would be taken into captivity by the Japanese for the duration of the war and subjected to hard labor. Rooks was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions aboard the Houston.

Medal of Honor Citation

For extraordinary heroism, outstanding courage, gallantry in action and distinguished service in the line of his profession, as commanding officer of the U.S.S. Houston during the period 4 to February 27, 1942, while in action with superior Japanese enemy aerial and surface forces. While proceeding to attack an enemy amphibious expedition, as a unit in a mixed force, Houston was heavily attacked by bombers; after evading 4 attacks, she was heavily hit in a fifth attack, lost 60 killed and had 1 turret wholly disabled. Capt. Rooks made his ship again seaworthy and sailed within 3 days to escort an important reinforcing convoy from Darwin to Koepang, Timor, Netherlands East Indies. While so engaged, another powerful air attack developed which by Houston’s marked efficiency was fought off without much damage to the convoy. The commanding general of all forces in the area thereupon canceled the movement and Capt. Rooks escorted the convoy back to Darwin. Later, while in a considerable American-British-Dutch force engaged with an overwhelming force of Japanese surface ships, Houston with H.M.S. Exeter carried the brunt of the battle, and her fire alone heavily damaged 1 and possibly 2 heavy cruisers. Although heavily damaged in the actions, Capt. Rooks succeeded in disengaging his ship when the flag officer commanding broke off the action and got her safely away from the vicinity, whereas one-half of the cruisers were lost.

Related Post: VIDEO The Battle of Java Sea and the USS Houston

Lt. Edward Henry “Butch” O’Hare – The First U.S. Navy’s Flying Ace in WWII

On 20 February 1942, Lt. Edward Henry “Butch” O’Hare became the first US Navy’s flying ace in World War II and was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in the South Pacific.

In January, the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) sailed from Pearl Harbor as the flagship of Vice Adm. Wilson Brown’s commanding Task Force 11 for the South Pacific. Lexington’s mission was to penetrate the enemy-held waters north of New Ireland and destabilize the Japanese position on Rabaul, an important Japanese base at the very tip of New Britain.

In mid-February, Lexington and Task Force 11 entered the waters of the Coral Sea and headed for a strike at Japanese shipping in the harbor at Rabaul scheduled for February 21. Aboard the USS Lexington was Lt. O’Hare with Fighting Squadron Three (VF-3) and their Grumman F4F-3 “Wildcats.”

The back of this postcard reads: “The Grumman ‘Wildcat’ is the standard single-seat fighting plane of the U.S. Navy. It operates from carrier or land base with equal facility. The ‘Wildcat’ has earned an enviable reputation in war action. Lt. Commander Edward O’Hare, flying a “Wildcat,” established a record for modern warfare by shooting down six Japanese bombers in fifteen minutes.” Postcard Gift of Robert Zeller, The National WWII Museum Inc., 2008.502.006

(more…)

Steward, Third Class Howard Madison Walker from Bowling Green, Kentucky and 78 crewmembers of the submarine USS Tang perished on October 24, 1944, when one of the subs torpedoes malfunctioned and struck her. Approximately 400,000 Americans lost their lives during WWII. Each of these heroes deserves to be remembered — their stories preserved and cherished for generations.

Steward, Third Class Howard Madison Walker from Bowling Green, Kentucky and 78 crewmembers of the submarine USS Tang perished on October 24, 1944, when one of the subs torpedoes malfunctioned and struck her. Approximately 400,000 Americans lost their lives during WWII. Each of these heroes deserves to be remembered — their stories preserved and cherished for generations.