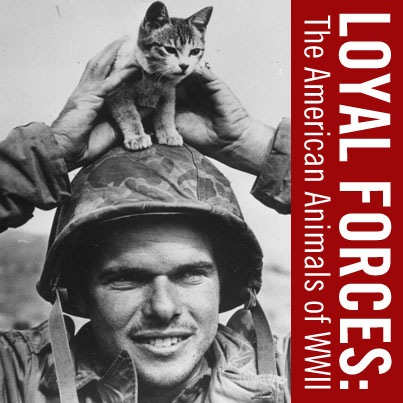

Loyal Forces – The American Animals of WWII

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Meet the Authors — Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II

Thursday, March 7, 2013

5:00 pm Reception | 6:00 pm Presentation

US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center

Join The National WWII Museum to celebrate the launch of Loyal Forces: The American Animals of WWII, written and compiled by the Museum’s very own Assistant Director of Collections, Toni M. Kiser and Senior Archivist, Lindsey F. Barnes.

At a time when every American was called upon to contribute to the war effort — whether by enlisting, buying bonds, or collecting scrap metal — the use of American animals during World War II further demonstrates the resourcefulness of the US Army and the many sacrifices that led to the Allies’ victory. Through 157 photographs from The National WWII Museum collection, Loyal Forces captures the heroism, hard work, and innate skills of innumerable animals that aided the military as they fought to protect, transport, communicate, and sustain morale. From the last mounted cavalry charge of the US Army to the 36,000 homing pigeons deployed overseas, service animals made a significant impact on military operations during World War II.

This event, held in the brand new US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center, is free and open to the public.

The Last Cavalry Charge

In 1941, as the Japanese continued to wage war on China, their need for oil, rubber, and other natural resources became desperate. Both the United States and Great Britain had placed embargoes on these items and frozen Japanese assets, making it increasingly harder for them to acquire the raw materials they needed to continue their war efforts in China. The Japanese took bold steps to ensure their gains in China would not be lost by invading the island nations in the Pacific. They hoped to secure oil from Borneo, Java, and Sumatra, along with rubber from Burma and Malaya. To secure shipping lanes for these raw materials, Japan invaded the American-controlled Philippine Islands.

Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright was commander of the Philippine Division, assigned to the post in 1940. Nicknamed “Skinny,” Wainwright was a 1906 graduate of West Point and a World War I veteran. His assignment as commander represented a significant achievement for Wainwright, with about 7,500 soldiers under his command. These soldiers were mostly Philippine Scouts, or native Filipinos who fought under the American flag. Also assigned to Wainwright was the 26th Cavalry Regiment, one of the last horse-mounted cavalries in the U.S. Army. Wainwright was a traditionalist when it came to the cavalry. His sentiments were that horse-mounted cavalry were some of the finest, most select, and most well-trained soldiers in the military. In his memoir, General Wainwright’s Story, he says of this unit that they were “to fight as few cavalry units ever fought.”

One officer of the 26th Cavalry Regiment was Lt. Edwin Price Ramsey. Like Wainwright, Ramsey believed the horse-mounted cavalry to be a superior unit of the military. His passion to remain in a mounted unit motivated him to volunteer to go to the Philippines in April 1941. He was assigned to lead Troop G, 2nd Squadron, of the 26th Cavalry Regiment. His troop consisted of twenty-seven men, all Filipinos, whom Ramsey was to train in mounted and dismounted drill. The men were disciplined, some having served close to thirteen years in the 26th, and Ramsey enjoyed working with them. It was with this troop that Ramsey was assigned his horse Bryn Awryn, a chestnut gelding fifteen and a half hands tall and with a small white blaze on his forehead. Bryn Awryn was powerful and well schooled, clever and aggressive, with the ability to turn on a dime.