Posts Tagged ‘Army Air Corps’

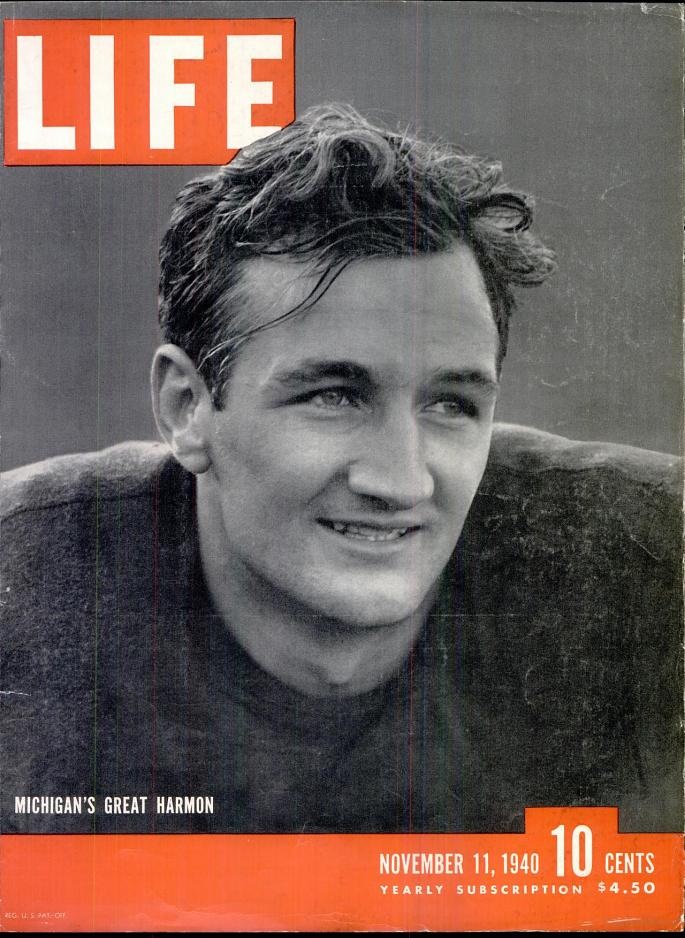

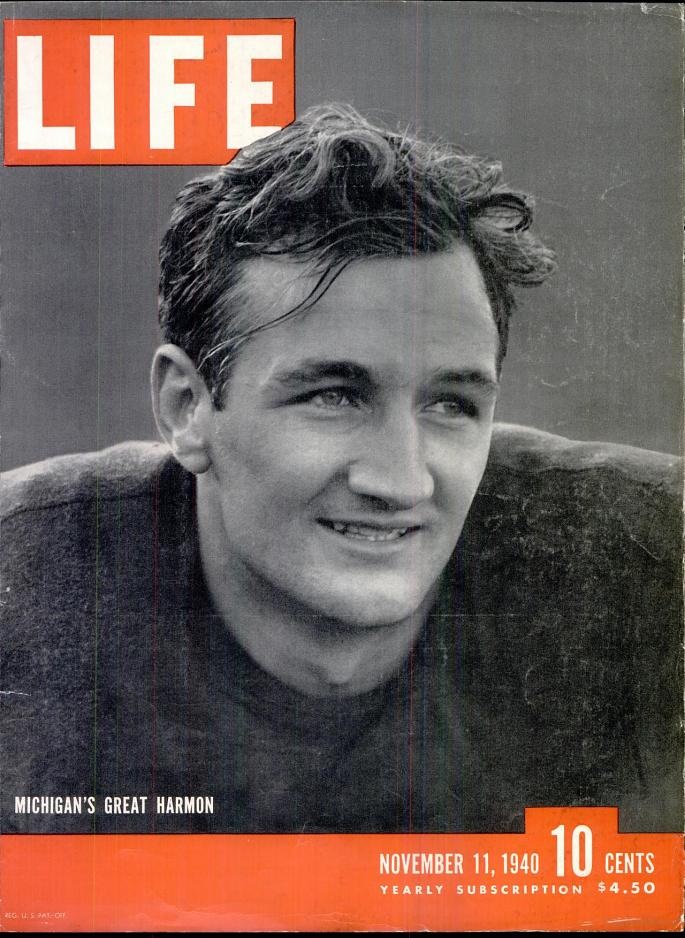

April 10, 1943 – Former all-America tailback at the University of Michigan and Heisman Trophy winner, Tom Harmon (US Army Air Corps) was the only member of his crew to survive a crash over Suriname due to weather conditions.

More About Tom Harmon –

Excerpt from Tom Harmon’s Obituary, The New York Times, March 17, 1990

Twice during World War II he was reported missing in action. In April 1943 he crashed into the jungles of Dutch Guiana, which is now Suriname, and marched alone through swamps and rain forests four days before he was rescued by natives.

Later that year, he bailed out of his P-38 fighter plane over China when it was shot down in an air fight. When he reached the ground, there were bullet holes in his parachute, and he pretended he was dead to discourage the enemy pilots from further attacks. He was smuggled back through Japanese-held territory to an American base by friendly Chinese bands.

When Harmon married Elyse Knox, an actress, on Aug. 26, 1944, the bride used the white silk and white cords from his parachute in her wedding gown.

After the war, Harmon received a $7,000 tax bill for earnings on the movie he had made in 1941. He accepted a $20,000-a-year offer from the Los Angeles Rams football team and performed for them through two unimpressive seasons. Wartime leg injuries robbed him of his former speed and power.

After ending his playing career, Harmon spent the rest of his life as a sports broadcaster in radio and television, based mainly in Los Angeles. In 1974, he joined the Hughes Television Network as a sports director, hired to coordinate sports programming and to serve as a commentator at major golf tournaments.

”Sports broadcasting was the only job I ever wanted,” he said. ”It was the thing I loved because it put me among people I knew and wanted to be with.”

The Michigan sports blog MGOBLOG also credits Harmon as the man who “made NCIS possible by fathering son, Mark.”

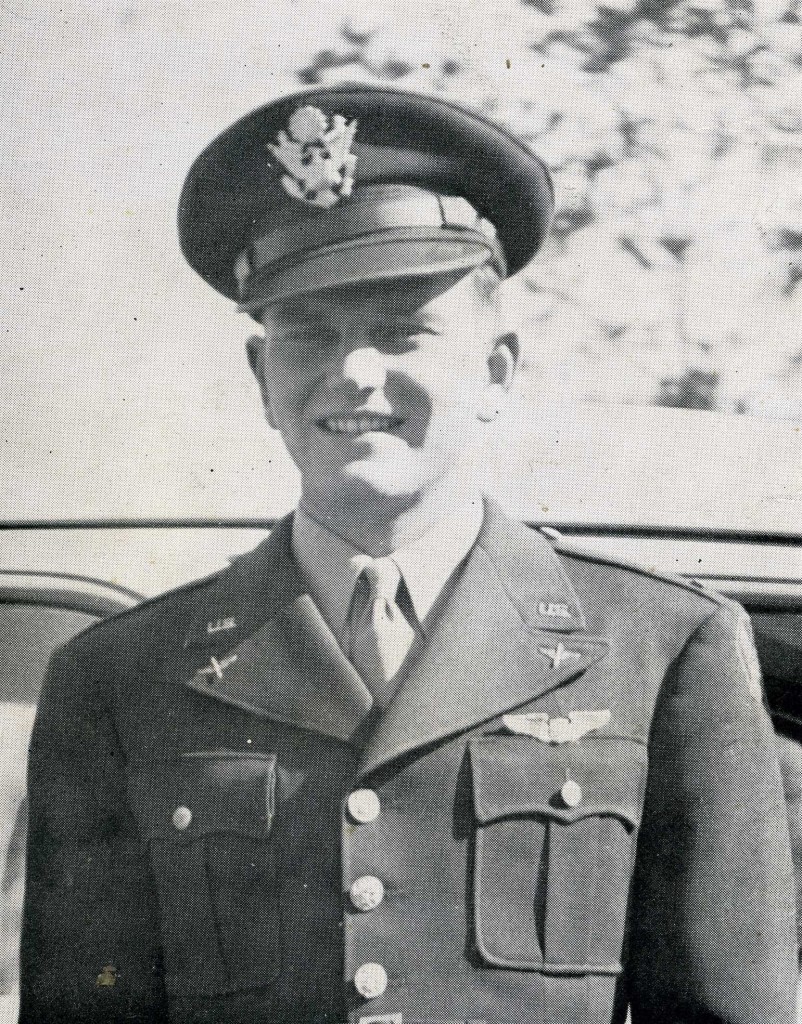

Tom Harmon (top row, center) and crew at Atkinson Field

We at The National WWII Museum were very sorry to hear about the passing of our friend, Senator George McGovern, over the weekend. As a WWII veteran, McGovern championed the Museum’s cause and we were fortunate to have him visit for a number of events, including the November 2009 grand opening ceremonies for the Solomon Victory Theater complex.

We at The National WWII Museum were very sorry to hear about the passing of our friend, Senator George McGovern, over the weekend. As a WWII veteran, McGovern championed the Museum’s cause and we were fortunate to have him visit for a number of events, including the November 2009 grand opening ceremonies for the Solomon Victory Theater complex.

On April 18, 2009, Senator McGovern also delivered a lecture entitled Wars Past and Present to a packed Museum house. Watch this lecture in its entirety.

In February of 2009, his oral history was added to the Museum’s permanent collection. This addition was highlighted in the Winter 2009 edition of the Museum newsletter, V-Mail.

Although Dr. George S. McGovern is best known for his years in the US Congress as well as for his 1972 bid for the Presidency, he also served in the US Army during World War II. During the latter years of the war in Europe, he was a young 2nd Lieutenant and a B-24 Liberator pilot. When he completed flight training and deployed overseas, he was assigned to the 741st Bombardment Squadron/455th Bombardment Group of the XVth Air Force based in Cerignola, Italy.

During the course of his time in Italy Lt. McGovern flew 35 combat missions, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross. His extraordinary bombing missions over central Europe and his experiences as a flight officer in the USAAF are chronicled in the book The Wild Blue by the late Dr. Stephen E. Ambrose.

A graduate of Dakota Wesleyan University, McGovern subsequently completed his Ph.D. in History at Northwestern University prior to entering the political arena.

In 2007, Senator McGovern supported the Museum’s effort to promote food drives. He spoke about how the war influenced his lifelong mission dedication to solving world hunger problems –

World War II introduced me to genuine human hunger for the first time in my life. I saw children handicapped and weakened by lack of food. I saw mothers and fathers in anguish, unable to provide adequate food for their families. I came back from World War II, where I served as a bomber pilot, determined to do what I could to help reduce world hunger, especially in children.

Our deepest sympathies are extended to the Senator’s family and friends as well as all who were touched by his life.

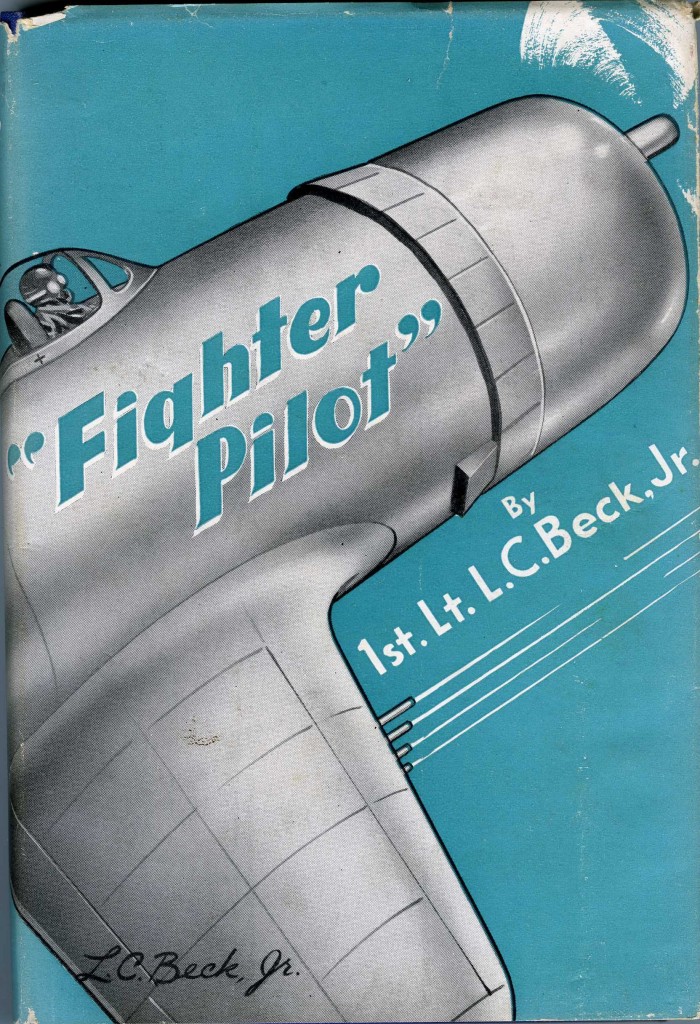

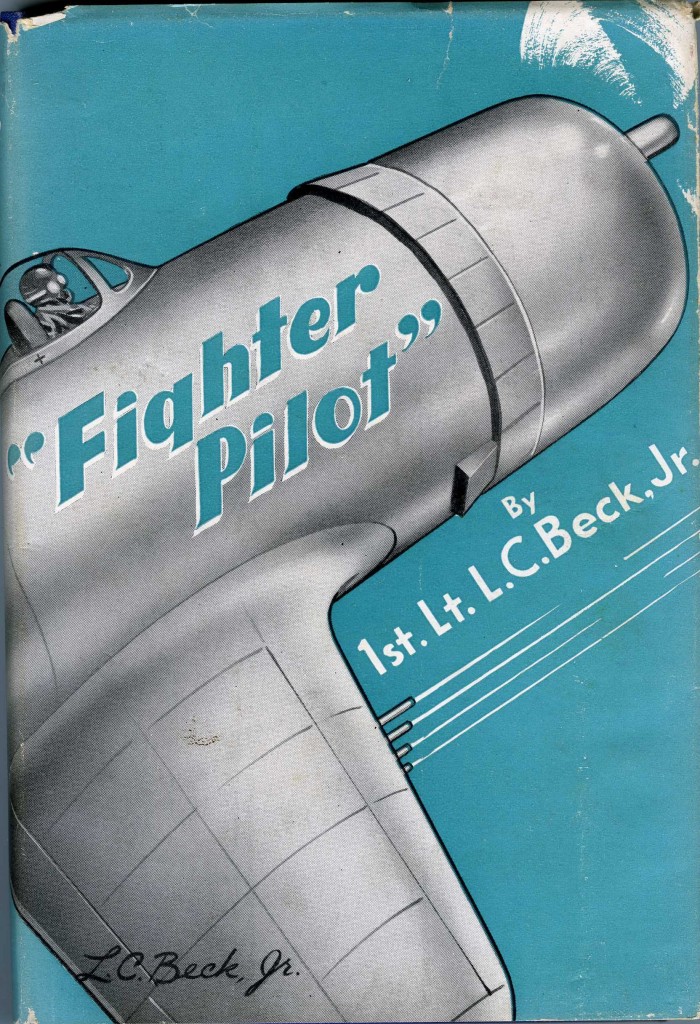

Fighter Pilot, an autobiography of an American pilot downed in German-occupied France.

Gift of James & Diane Riddle, 2012

Seventy years ago today, a young man named Levitt Clinton Beck enlisted in the Army Air Corps, making a lifelong dream a reality. Having flown solo since the age of 16 and already having logged more than 60 solo hours, Beck felt more prepared than most to take war to the skies. But nothing could have prepared L. C. for the five-month ordeal that he would face after a forced emergency landing in occupied France.

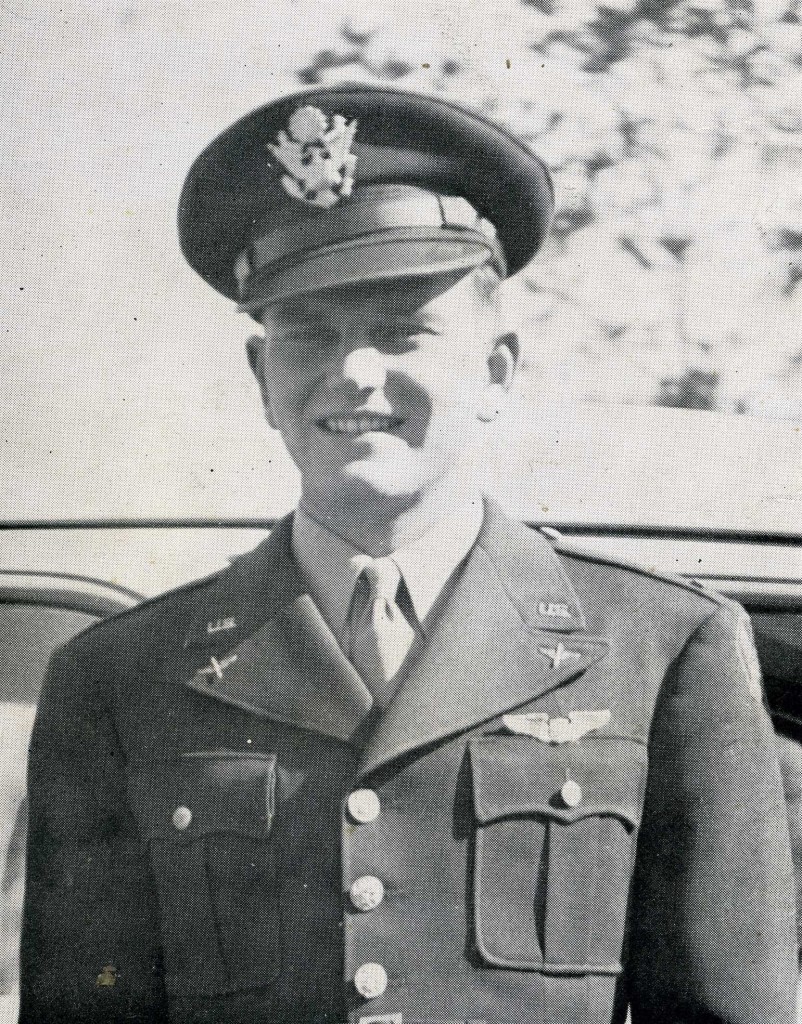

After a year of training around the United States, Beck received his wings—one of the fondest memories of his career—and was quickly promoted to 1st Lieutenant. Shipping out as part of the 514th Fighter Squadron, 406th Fighter Group, Beck arrived in England to prepare for participation in the largest amphibious invasion in history: D-Day.

Taking to the air at 0330 hours in total darkness that could only be made worse by the prevalence of low-lying clouds, Beck and his fellow P-47 pilots had to fly from memory of navigation charts. The squadron ended up off course a few times, but eventually made it to the invasion beaches where they had a bird’s eye view of the unimaginably vast armada steaming towards Normandy. There were no Jerry’s in the air to oppose them, so they headed back to England unscathed.

Lieutenant L. C. Beck

Less than a month later on 29 June 1944, the entire group took up their 47s to search for bridge targets on the Seine in German-occupied France. Beck’s squadron served as cover for the bombers. Beck lost sight of his squadron for a moment; when he found them they were joined by a pair of Focke-Wulf 190s spitting bullets in their direction. Beck chased him down, and scored his first victory. Like a lion with its cub, the second 190 sought to retaliate, leaving the other 47s be. As Beck tried to pull up and react, he realized his first victory came at the cost of his engine which his prey had managed to shoot out. The second 190 saw that Beck’s 47 was earthbound and pulled up.

Beck had experience with emergency landings both from training and a more recent experience over Cherbourg just a few days before. He successfully bellied down in a wheat field and immediately heard the sputter of an MG42 raking for him. Only later would he find out that the pilot of the first 190 had bailed out and was being shot at by his own men who believed him to be the amerikanerin.

Beck high crawled to the outer rim of the field, and saw civilians approaching. He was told in French to hand over his weapon. He didn’t speak a lick of French, and wasn’t exactly in a situation to say no. Beck had to trust the Frenchmen weren’t collaborators. Luckily for him, they were members of the resistance who had experience hiding downed Allied airmen and getting them back to England.

Beck was taken to Anet, a small French town a few dozen miles southwest of Paris. His saviors gave him civilian clothes—including a beret of course—and took him to Madame Paulette Mesnard, the proprietor of a small café in town. Beck was to hide out in a small but cozy room above the Café de la Mairie until given further instruction.

Mme Paulette’s cafe in Anet, France. The circled window indicates Lieutenant Beck’s hideout.

It was while in isolation in this room that received electricity for two hours a day that Beck decided to write Fighter Pilot, dedicated to his parents. He wrote the entire manuscript on the backs of menus from Mme Paulette’s restaurant. Much of the story is in the form of letters home to his parents and his girlfriend, expressing longing to have a few “bald-headed pilots” of his own; to play his tenor sax again; wondering what a quiet, peaceful life would feel like when he got home. He described D-day and his first victory, as well as his landing and introduction to the resistance.

After two weeks of being pent up at Mme Paulette’s, Beck received direction from his newfound friends that he was to make a trip to the tiny village of Les Vieilles Ventes, from where he would catch a plane back to England. Before leaving Anet, he buried his manuscript in a box inside a box in Paulette’s backyard. He intended to retrieve it after the war, but instructed Paulette to send it to his parents if he failed to return.

Beck stayed in Les Vieilles Ventes for another week, when he was picked up by a fellow resistor known only as Jean-Jacques who drove Beck to Paris. When the next day the Gestapo picked up Beck, he realized that Jean-Jacques was no resistor, but a full-on collaborator. Imprisoned in Fresnes, Beck was denied the normal rights of a prisoner of war. He was treated the same as the political prisoners held there, and arguably worse since he was considered a “terrorist” – Allied airmen not wearing their uniform or a dog tag behind enemy lines were consider illegal combatants, and therefore were not given the “privilege” of POW status.

The Germans knew the Americans were quickly approaching, and moved the entire prison contingent to Buchenwald. Coincidentally, there were 168 other Allied Airmen who had also been sent to Buchenwald in August 1944. Of the 168 imprisoned airmen, Beck was one of only two that perished in the camp before the others were transferred shortly after. Madame Paulette kept her promise and sent Beck’s manuscript to his parents, who then had a few copies published in his honor. One of these has been donated to The National WWII Museum where it will be preserved for future generations.

“I am glad that I was destined to become a fighter pilot, even though it may cost me my life. I am proud that I can fight for that which is right. I feel sorry for anyone who cannot.”

The traitor known as “Jean-Jacques” was Jean-Jacques Desoubrie, an electrician and member of the Gestapo who was captured after the war. He was put on trial, convicted, and executed in December 1949. The story of the 168 fliers he was responsible for sending to Buchenwald is not a well known one, but has recently been given some attention through the documentary “The Lost Airmen of Buchenwald.” The fliers stuck together in the camp and maintained military standards, always marching in formation and doing what they could to maintain a clean and dignified appearance among the filth and disorder of the camp. The survivors, who call themselves the KLB Club—short for Konzentrations lager Buchenwald Club—share their unique and harrowing story in the documentary. Through their story and his own Fighter Pilot, Lt. L. C. Beck is remembered.

This post by Curator Meg Roussel

We at The National WWII Museum were very sorry to hear about the passing of our friend, Senator George McGovern, over the weekend. As a WWII veteran, McGovern championed the Museum’s cause and we were fortunate to have him visit for a number of events, including the November 2009 grand opening ceremonies for the Solomon Victory Theater complex.

We at The National WWII Museum were very sorry to hear about the passing of our friend, Senator George McGovern, over the weekend. As a WWII veteran, McGovern championed the Museum’s cause and we were fortunate to have him visit for a number of events, including the November 2009 grand opening ceremonies for the Solomon Victory Theater complex.