Donor Spotlight: The Lupo Family in honor of Alvena & “Commodore” Thomas J. Lupo

The General Motors TBM Avenger’s primary function was that of a torpedo bomber and was used in multiple countries, including the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia during the war. The Avenger’s combat debut was at Midway in 1942. Six Avengers from Midway Island attacked the Japanese carrier strike force, but only one bullet-riddled Avenger made it home to Midway. None of the planes scored hits on the Japanese ships, but despite this disappointing result, the Avenger served as the US Navy’s primary torpedo bomber, effectively interdicting enemy shipping and delivering ordnance on enemy positions throughout the Pacific.

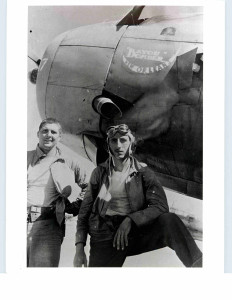

The Museum’s TBM Avenger has been generously donated by the Lupo Family in honor of Alvena and “Commodore” Thomas J. Lupo. Former Museum Board of Trustee Member Thomas J. Lupo, enlisted in the United States Navy and served as an aviator in the Pacific. He was known to his colleagues as “Lucky Loop,” and served with distinction aboard the USS Fanshaw Bay. The aircraft in US Freedom Pavilion: is painted to look like Lupo’s “Bayou Bomber.”

Donor Spotlight: Robert and Mary Lupo

The General Motors TBM Avenger located in the US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center has been made possible through a generous gift by The Lupo Family in honor of Alvena and “Commodore” Thomas J. Lupo.

Robert E. Smith Lupo first met his wife Mary when they both attended a fraternity party at Tulane University in 1972. Robert recalls he poked fun at Mary when she first entered, carrying a glass of champagne, and the two soon hit it off. They married in 1980 after Mary graduated from medical school.

Robert and Mary first became involved with The National WWII Museum through Robert’s late father, Thomas J. Lupo. The elder Lupo was a former Museum Board of Trustees member and a Navy veteran of WWII, having served as an aviator in the Pacific. He was known to his military buddies as “Lucky Loop,” due to his successful attack runs on the IJN Yamato¸ one of the largest battleships in history. He earned many combat medals and citations for his heroism, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Philippine Legion of Honor and the Purple Heart. In 1986, the Military Order of the World Wars presented to “Commodore” Lupo its highest award for patriotism, the Silver Medallion Patrick Henry Award.

The Lupo family has been a part of The National WWII Museum family since its creation. Robert spoke of father’s participation in early discussions with Stephen Ambrose of the historian’s dream of building a WWII museum in New Orleans, initially focusing on D-Day invasions. Today, decades later, the Lupo family continues to proudly support the Museum, helping to advance its mission.

The Lupo family generously sponsored the General Motors TBM Avenger warbird that currently hangs in the US Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center. The aircraft is depicted as Lt. Thomas Lupo’s “Bayou Bomber” Avenger, flown during battle. At the dedication ceremony for the Avenger, Robert recalled that his father was incredibly proud to be honored in this way, and Mary said “there are no words” to describe the emotion the family felt.

Robert states that the family sponsored the Avenger to honor his father and to provide an educational tool for future generations. He believes that all humans strive “to leave something, whether it’s to our kids or community” and that giving to the Museum is an “incredible opportunity to leave something that continues to teach.” As Mary puts it, “It’s almost your patriotic duty if you can give.” The Lupos believe that it is important to support an institution that reaches across the generations. Mary calls the Museum “the thing in the city that I am most proud of.”

We are honored by Robert and Mary Lupo’s advocacy for the Museum’s cause and grateful for all they do to support the capital expansion.

- Posted :

- Post Category :