Get in the Scrap! Wrap-Up

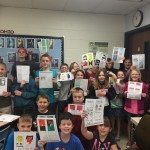

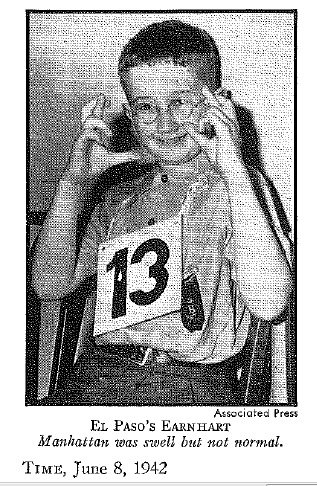

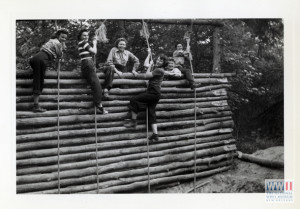

The school year has officially reached a close, and with that came the end to the first year of The National WWII Museum’s Get in the Scrap! service learning program on May 31. This project, which took each school about 1 to 3 months to complete, focused on the importance of recycling and conserving energy today through explanation of why scrapping was so important on the Home Front during the World War II era. This program offered students from fourth to eighth grade a parallel to the lives of students their age during the war.

Get in the Scrap! called students to save items like water bottles and pennies as well as encouraged them to read primary sources about school salvage drives to collect rubber, steel, plastic, and paper on the American Home Front. These items were used to create weapons, supplies, and other necessities that the soldiers required to fight in both the European and Pacific Theaters. Some students who participated in Get in the Scrap! took a creative approach to the scrapping effort by decorating light switch plates and crafting with their left over water bottles.

Others found their competitive sides in a Penny War, which was one of the most popular activities for the schools. The Penny War is a one-week long competition to see which class could save the most pennies, and at the end of the week they could donate their savings to a charity of their choice or invest in purchasing new recycling bins for their school. At LT Ball Intermediate School in Tipp City, Ohio, the students who completed the Penny War donated their savings to the Honor Flight, which is a non-profit organization that helps veterans travel to Washington, D.C. to visit memorials and monuments dedicated to their service.

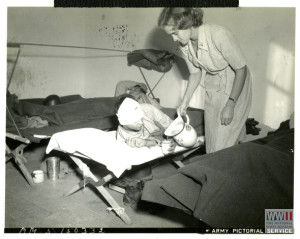

Overall, Get in the Scrap! had a positive impact on all of the participants. Many teachers reported back that their classes had become more environmentally aware. Some even took what they had learned and applied it outside of the classroom by asking their parents to buy recycle bins for their homes. Other teachers said that this project significantly drew their students’ interest to World War II history. Chesapeake Academy had a WWII veteran come in a speak with the students about life both the Home Front and battlefronts during the war.

Get in the Scrap! will pick up again with the new school year this coming September. You’ll find more photos and successes of our students who participated this past year using the hashtag #getinthescrap on Twitter or Instagram. Sign up for the Museum’s monthly e-newsletter “Calling all Teachers!” for the latest Get in the Scrap! news and project updates.

Post by Camille Weber, Education Intern and Chrissy Gregg, Virtual Classroom Coordinator

- Posted :

- Post Category :