SciTech Tuesday: Inventing dialysis under Nazi occupation

Sausage casings, juice cans, and a washing machine were key components of the first artificial kidney. The dedication, inventiveness, and courage of a doctor under Nazi occupation were important too.

Willem Kolff was a young Dutch physician who read, in the late 1930s, of research done in 1913 by John Abel at Johns Hopkins University. Abel had conducted some animal studies on hemodialysis, and Kolff thought he could use similar methods in his practice. By the time Kolff was making progress, the Germans occupied the Netherlands, and he was sent to work in a rural hospital.

Forging documents, and pressing his wife and colleagues to help him continue his investigations, Kolff constructed the first drum dialyzer. He treated many patients with failing kidneys unsuccessfully until he managed to revive a comatose 67 year old woman whose kidneys were not working.

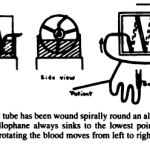

Drum dialyzers work by filtering the blood with an artificial membrane rotating around a cylinder. The device Abel tested on animals used vegetable parchment coated with egg albumin to filter blood, and an extract of leeches to prevent coagulation. Kolff’s original device used sausage casing as a membrane, and after the war he used cellophane tubing. He used heparin to reduce coagulation.

During the war Kolff managed to make 5 dialysis machines, and at the war’s end he donated them to hospitals around the world, eschewing patent rights in the hope that others would help him improve treatment for kidney failure.

He accompanied one of the machines to Mt Sinai hospital in NY, where some medical staff were horrified by the thought of treating blood outside the body. With a researcher at Brigham Hospital in Boston, he developed the Kolff-Brigham dialyzer, made of stainless steel—a big improvement from used cans and sausage skins.

The Kolff-Brigham dialyzer was used to save many soldiers in the Korean War, and Kolff continued to work on dialysis and artificial organs for his whole life. Willem Kolff was born Feb 14, 1911, and died Feb 11, 2009.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum.

Are you, or do you know, a science teacher of students in 5th-8th grades? We are looking for members for the 2016 Real World Science Cohort. Spend a week at our museum, learning all about how to teach hands-on science with connections to history and literacy. Apply now–applications accepted until March 4, 2016.

Images are from Kolff et al 1943, available here

- Second generation versions of Kolff's dialyzer, these machines used cellophane tubes in place of sausage casings.

- A diagram of how Kolff's second generation dialyzers worked.