Posts Tagged ‘U-boats’

Put on your thinking caps, it’s SciTech Tuesday! This series will feature stories and photographs of the science and technology that helped to win a war. Be inspired by the innovative spirit of the scientists, mathematicians, engineers, service members and civilians who answered the call to create, design and build the technologies of World War II. Make a historical connection to the scientific advancements of today.

Courtesy of KAHEA.

Recent Discovery of German U-boat Uses WWII Technology

Last Monday, divers found U-550, a German submarine which sank off the coast of Nantucket following an epic battle at sea on April 16, 1944. In a true twist of irony, the same sonar technology used by the Allies to locate and destroy the doomed U-boat, ultimately led to its discovery by a privately funded group almost 70 years later.

SONAR (SOund NAvigation and Ranging) uses emitted sound waves to detect the position of objects below the surface of the water. Sound waves, created by the vibration of an object, exist as differences in pressure moving through a medium such as air or water. Sonar transducers produce a pulse of sound into the water. Any object in the path of the sound pulse will block the wave causing it to bounce back toward the transducer, which will detect the returning sound wave, or “echo.” Because the speed of sound through water is constant, the distance of the detected object from the transducer can be determined by the amount of time that passes between the initial pulse and returning echo.

Making Connections Between the Science and Technology of WWII and Today.

Back on April 16, 1944, the sailors of the USS Joyce and USS Peterson used sonar to detect the position of U-550 and drop depth charges, severely damaging the submarine. Before the German crew abandoned ship, they set explosions to sink the U-boat and prevent its recovery by the allies. The ill-fated U-550 had not been seen again until last Monday, when the research team located the submarine using side scan sonar, a modern advancement upon sonar technology used during World War II.

Sign up for our monthly Calling All Teachers eNewsletter

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum.

Canadian sailors operating ASDIC, an early form of SONAR -Photo by William H. Pugsley- National Archives of Canada- PA-139273

Crew members aboard the USS Joyce watch as the German submarine U-550 sinks after being depth charged on April 16, 1944. Joyce rescued the surviving 13 crew members.

After the U-boat slaughter of May 1942, a convoy system was put in place for Allied merchant vessels in the Gulf of Mexico in an attempt to bring an end to the German offensive known as Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat). Although the threats on Allied vessels were lessening towards the end of July 1942, U-boats were still active in the Gulf. One of at least ten U-boats still on the prowl in the summer of 1942 was U-166, under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Günther Kuhlmann. After laying mines near the mouth of the Mississippi River and sinking three American vessels (the SS Carmen, SS Oneida, and SS Gertrude on June 11th, 13th, and 16th respectively), U-166 had an encounter with American vessels seventy years ago today, on 30 July 1942, that ended in tragedy.

On 30 July 1942, the SS Robert E. Lee was en route from Trinidad to New Orleans with 270 passengers escorted by the naval vessel, PC-566. Near Tampa, the captain tried to bring the ship into harbor, but was forced to continue on to New Orleans because of the lack of a harbor pilot. The Robert E. Lee was carrying additional passengers, survivors of U-boat attacks on the Norwegian motor tanker, Andrea Brøvig and the Panamanian steam tanker, Stanvac Palembang. Only twenty-five miles south of the mouth of the Mississippi River, the Robert E. Lee was hit by a single torpedo from U-166. Most of the passengers were able to squeeze onto the sixteen life rafts and six lifeboats. As the ship went down, Kuhlmann surfaced U-166 and shouted to the survivors, apologizing and wishing them luck (a practice that had been seen before). As the U-166 dove under the surface, PC-566 dropped depth charges, in hopes of hitting the U-boat. Ten crewmen and 15 passengers were lost aboard the SS Robert E. Lee. One of the crew killed aboard the Robert E. Lee was a female mariner from New Orleans, Winifred Grey.

Although it was not immediately clear if U-166 had been hit by the depth charges, indeed the retaliatory attack by PC-566 was successful; U-166 was lost, resulting in the deaths of all 52 members of the submarine crew. The location of the wreckage of the Robert E. Lee had long been identified, close to the site of the U-boat attack, 45 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi. But it wasn’t until 2001 that BP and Shell discovered the wreckage of the U-166, close to that of the Robert E. Lee. After the vessel was located, a film crew documenting the discovery of the U-boat learned from Kuhlmann’s widow of the existence of a large collection of images from Kuhlmann’s service. She subsequently donated this material to The National WWII Museum through the PAST Foundation. More information can be found here. A selection from the material gifted by Kuhlmann’s widow can be seen below. It provides a rare and fascinating glimpse into the private life of an often demonized enemy.

-

- Hans-Günther Kuhlmann.

-

- Hitler appeared at a ceremony for new officers including Kuhlmann, on 17 January 1939.

-

- June 1940 wedding announcement for Kuhlmann and Gertrude Wree.

-

- Kuhlmann and his bride after the wedding ceremony.

-

-

- Promotion certificate for Kuhlmann signed by Erich Raeder.

-

- Condolence letter from March 1943 listing Kuhlmann's death as having occurred in the Caribbean on 3 August 1942.

-

- Condolence letter from November 1942 from the Guenther Kuhnke, Commander of the 10th U-boat Flotilla, which explains that the fate of her husband is unknown.

-

Post by Curator Kimberly Guise.

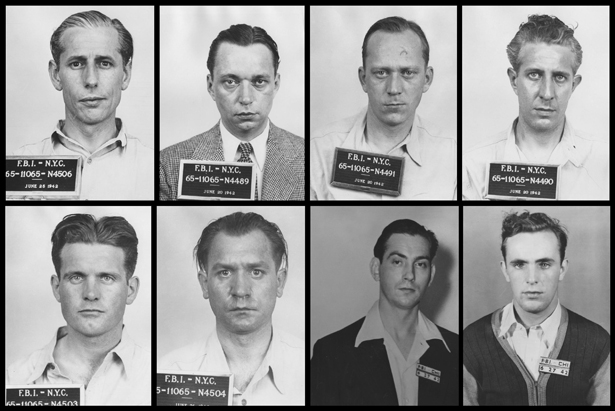

German attempts at sabotage and espionage in North America led to several arrests without the successful completion of any of the objectives.

Most people think of the U-boat as only being a highly efficient ship-killer, but it also supported espionage, intelligence gathering and sabotage operations throughout the war. These missions were carried out at points throughout Europe, on the coast of Africa, within the Arctic Circle and even in the Americas. Before the end of the war, U-boats made landings in North America on six separate occasions.

The first landing occurred on May 14, 1942, when U-213 put Abwehr agent Alfred Langbein ashore near the village of Saint John on the Bay of Fundy coast of New Brunswick. Langbein spent the next two years in hiding without doing any spying at all before finally turning himself in to Canadian Naval Intelligence in Ottawa in September 1944.

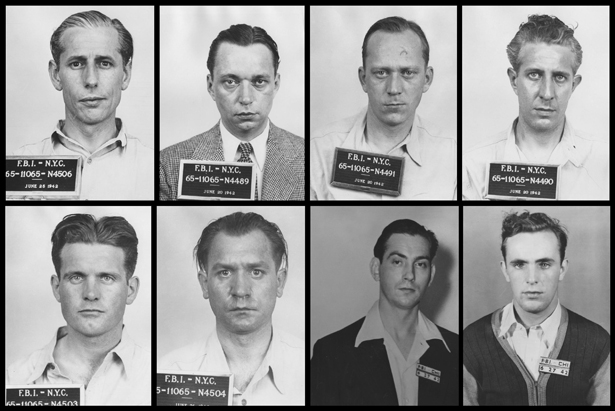

Before dawn on June 13, 1942, U-202 put four saboteurs ashore near the village of Amagansett, Long Island as a part of Operation Pastorius. Three nights later, U-584 landed another group of four saboteurs near Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. The two groups were to use explosives to destroy railroad bridges, defense plants and factories crucial to US military aircraft production. The Long Island Group made their way to New York City where the team leader George John Dasch decided to turn himself in. Because of his cooperation the FBI was able to round-up the remaining saboteurs. All eight men were convicted of espionage by a military tribunal in Washington, DC. Six were executed by electric chair on August 8, 1942. The other two were ultimately deported back to Germany in 1948.

The fourth landing occurred during the night of November 9, 1942, when U-518 surfaced in Chaleur Bay in eastern Quebec and put Abwehr agent Werner von Janowski ashore near the village of New Carlisle. With his unusual clothing and foreign accent, Janowski stood out among the Québécois like a sore thumb, resulting in his arrest by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police the next day.

The fifth and perhaps most interesting landing began early in the evening of October 22, 1943, when U-537 anchored in Martin Bay just south of Cape Chidley on Canada’s Labrador Coast. The following morning, personnel from the U-Boat assembled an automated weather station on a hill overlooking the bay. The station functioned for only a day before mysteriously falling silent.

The final North American landing occurred when U-1230 put ashore Abwehr agents Erich Gimpel and William Curtis Colepaugh at Hancock Point on Frenchman’s Bay, Maine shortly after midnight on November 30, 1944. Gimpel and Colepaugh (a native born American) were given the ambitious task of infiltrating the aviation industry and the Manhattan Project. The agents made their way to Portland, Maine and then on to New York City where Colepaugh lost his nerve and turned himself in to the FBI. Gimpel was arrested soon thereafter bringing Germany’s final attempt at espionage in North America to an unsuccessful conclusion.

A view of U-537 anchored in Martin Bay on the Labrador Coast of northern Canada

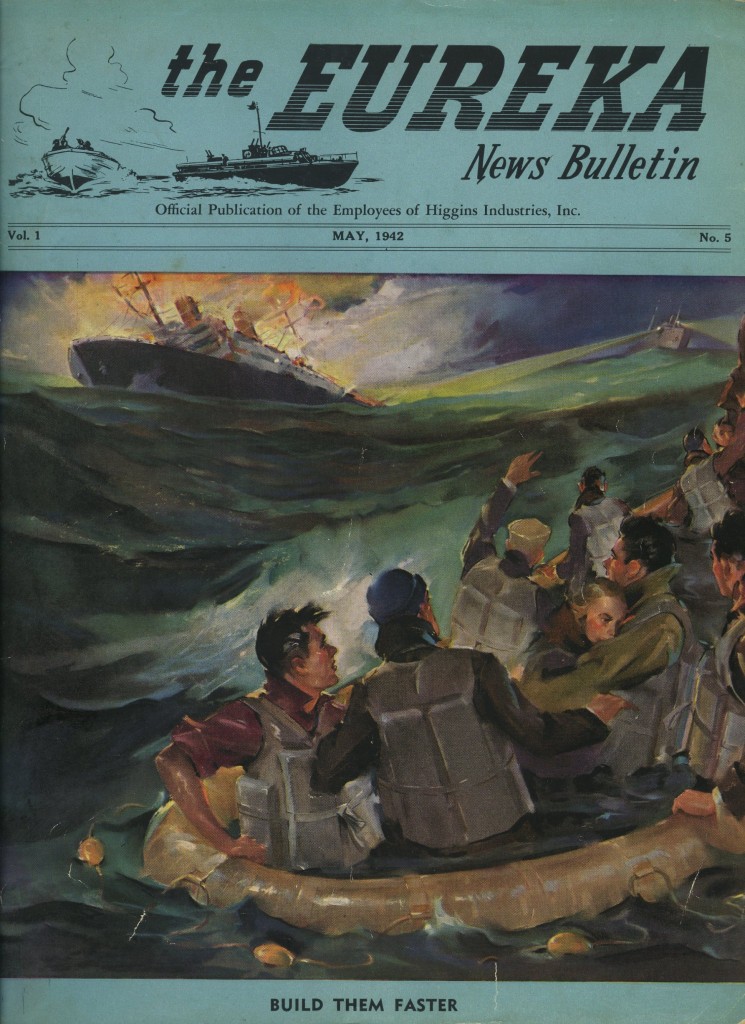

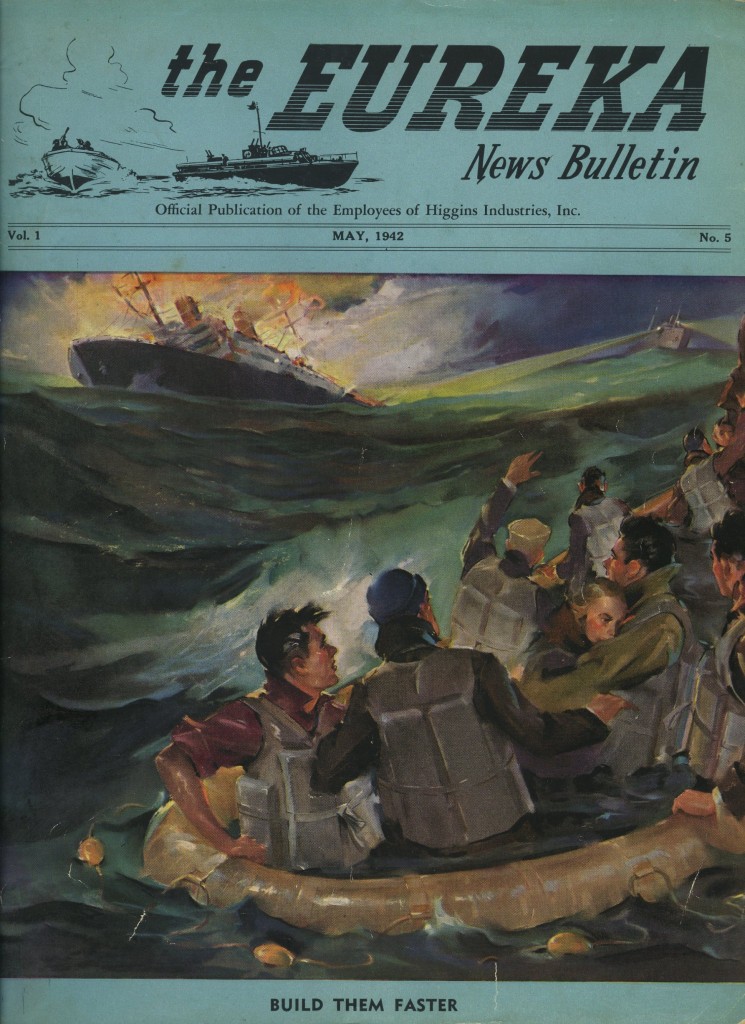

May 1942 was the busiest month of the war for U-boat activity in the Gulf of Mexico. The SS Alcoa Puritan was just one of the vessels that fell victim to a U-boat this month 70 years ago. The May 1942 cover of The Eureka News Bulletin shows a steamship ablaze after an encounter with a U-boat; the steamship’s crew members are adrift in a life raft. On 12 May 1942, the tanker SS Virginia was sunk by U-507 as it entered the mouth of the Mississippi—the closest such attack the Louisiana coast would see during WWII. Twenty-six crewmen were killed.

For more posts about the publications of Higgins Industries and production on the home front during WWII, see the series Worker Wednesday.

Post by Curator Kimberly Guise.

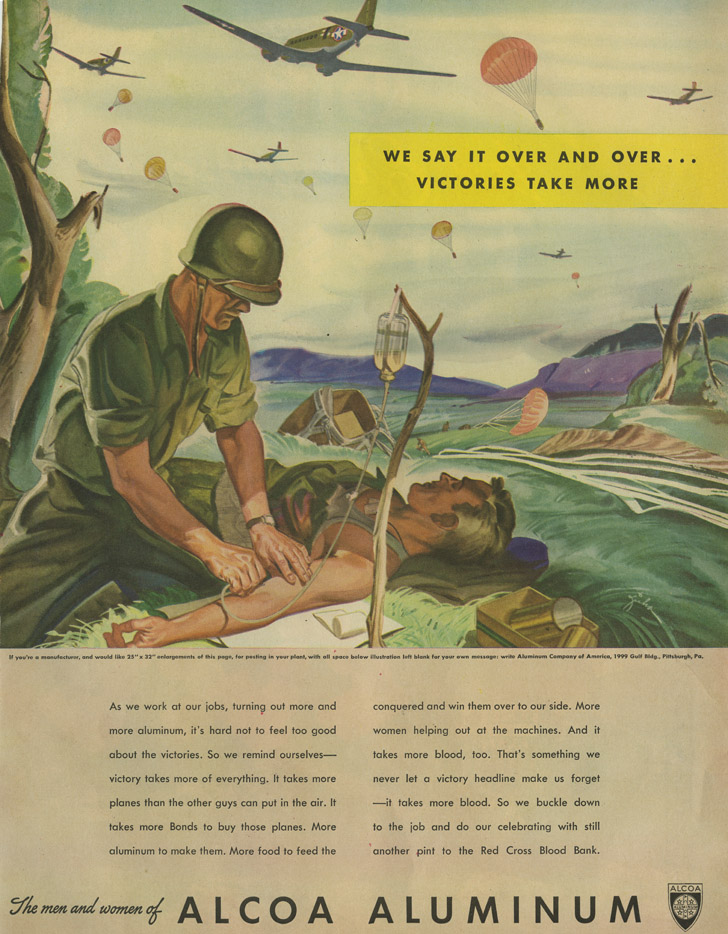

Gift of Dr. Frank Arian, 2009.451.377

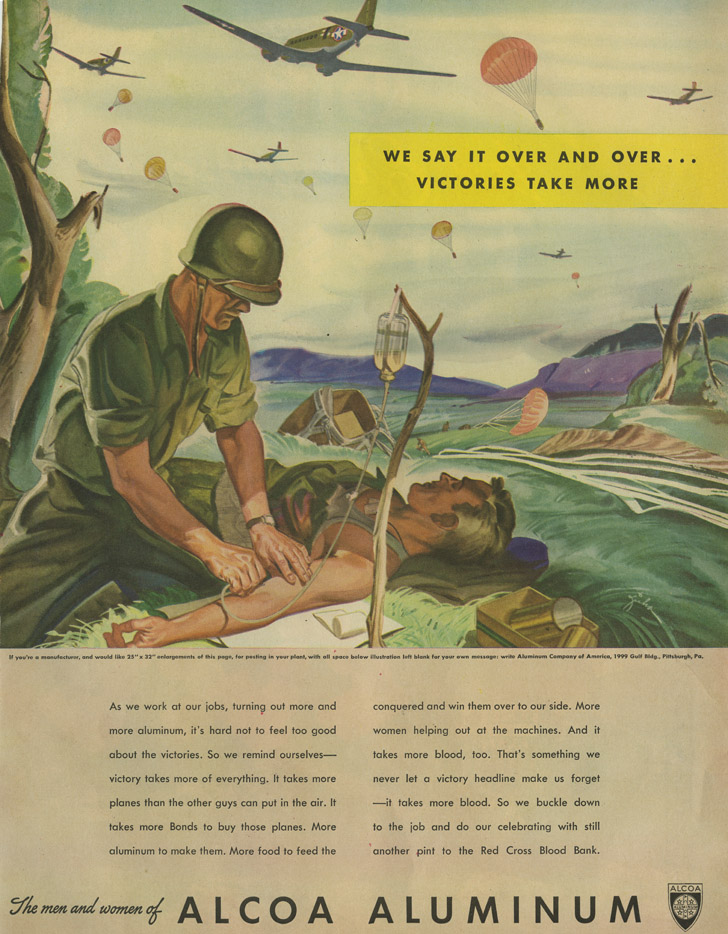

Seventy years ago today on 6 May 1941, the SS Alcoa Puritan fell prey to U-507 in the Gulf of Mexico only about 50 miles south of the mouth of the Mississippi River . In May 1942, nearly a ship a day was lost in the Gulf of Mexico, victim to German U-boat wolfpacks. In 1942 and 1943, U-boats would sink fifty-six ships and damage another fourteen in the Gulf alone. It would not be until late July 1942 that merchant ships began a convoy system in the Gulf to help bring an end to this threat to sailors lives and critical supplies.

The Alcoa (Aluminum Company of America) operated SS Alcoa Puritan was on its way from Trinidad to Mobile, Alabama with a load of bauxite, the main source of aluminum and chief product of Alcoa, when it was targeted by U-507. After the Puritan was disabled by over 70 shells from the U-507’s deck guns, Captain Yngvar A. Krantz gave orders to abandon ship. The German submarine’s captain waved and even apologized to the crew before submerging. The Puritan’s entire crew and her passengers (which included 6 survivors from a previous torpedo sinking) were rescued by a Coast Guard cutter less than an hour later.

The wreck of the Alcoa Puritan was discovered in 2002 by contractors conducting surveys for Shell International Exploration and Production. That discovery has sparked research studies by marine archaeologists about the archaeological and biological analysis of World War II shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico. In 2004, the Minerals Management Survey donated a German 10.5cm shell casing recovered from the Gulf of Mexico to the Museum. The shell casing was found just north of the wreck of the Puritan and is presumably from the deck gun of U-507.

Shell casing from the U-507

Gift of the Minerals Management Service, 2004.392

Read more about these studies and about the SS Alcoa Puritan and U-boats in the Gulf here.

Post by Curator Kimberly Guise.