“It was so good to see your handwriting.”

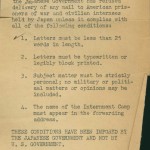

Those of us who work with archival collections come into contact with unique handwriting nearly every day. Although we can normally decipher the script (predominantly English in our collection), from WWII, there are times when we have to poll colleagues and guess at what is written. Does it say —? There were times when handwriting played a more central role in communication. In writing to prisoners of war, especially in the Pacific, where letters would be read by both American and Japanese censors, writers received special instruction. Most importantly, the letters were to be short (no more than 25 words) and were to be typed or block printed. Letters that did not comply with these rules, were returned.

We have examples of these failed attempts at communication from a collection of material related to the imprisonment by the Japanese of USMC Sgt. Edward A. Padbury. POWs in Japan were allowed very little, if any, correspondence with their loved ones. Mail was regularly delayed by nearly a year. General Jonathan Wainwright’s wife, Adele, reportedly sent him 300 letters over the three-plus years of his imprisonment. He received a total of six.

Catherine Faye, Edward Padbury’s sister, had some unsuccessful efforts to write to her brother. The first letter was returned on two accounts. It was longer than 25 words and written in cursive. The second letter was block printed, but also too long. We do not have any correspondence from Sgt. Padbury, but we do know that he survived the war and was liberated from Shinjoku POW Camp in the Tokyo Bay area.

Gift of Phillip Faye, 2006.128

Post by Curator Kimberly Guise.

Leave a Reply