Executive Order #9066: 70th Anniversary Japanese Internment Februrary 19, 1942

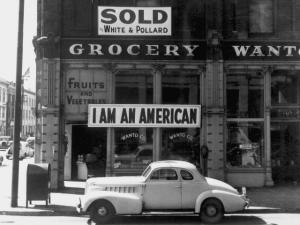

The decision to intern American citizens of Japanese descent in early 1942 is today regretted as one of the most disreputable civil rights abuses in American history. It is an event which seems almost unthinkable for contemporary American society, and as such is a poignant and necessary reminder of the degree of peace we enjoy in our world today, and how different was the atmosphere of the Second World War.

Before Pearl Harbor, Japanese-Americans living in the United States were generally divided into two groups: the Issei, who were native born Japanese who had emigrated to America and constituted over a third of the total, and the Nisei, who were born of Japanese parents within the United States. However, many amongst the Nisei held dual citizenship in both the United States and Japan due to the differing citizenship laws of the two nations. In Japan, citizenship was conferred until 1916 through familial relations (paternal jus sanguinis); any child born to a Japanese father was considered to be a Japanese citizen. In the United States, any child born upon American soil (jus soli) was considered to be an American citizen. It should be noted that the Japanese government amended their citizenship laws twice in the 25 years before Pearl Harbor. In 1916, the Japanese government allowed Nisei or their guardians to retroactively renounce Japanese citizenship; and then in 1924 the Japanese government eliminated automatic citizenship of foreign-born children, although the children were eligible for Japanese citizenship if their parents applied for it within two weeks of their birth. Nevertheless, a large number of Nisei, particularly those born before 1924, held dual citizenship with Japan, even if they did not know it. This contributed to the perception of divided loyalties once the war began.

Amongst the young Nisei, there was a further divide. Many Nisei in the United States attended public schools and were thoroughly assimilated to American ways, but also attended Japanese schools organized by the Issei in their hours after public school. This was meant to bridge the gap between the Issei, who spoke mainly Japanese, and the Nisei who mainly spoke English. In these schools, Nisei learned and studied Japanese language, history and geography as a cultural connection to their native homeland. But there was a subgroup of Nisei who traveled back to Japan to study there; these were known as the Kibei, who then returned to the United States after their education. Because of their advanced Japanese language skills, many Kibei were became valuable translators in the U.S. military later during the war. It is estimated that there were slightly over 10,000 Kibei of the total of approximately 126,000 Japanese-Americans living in the United States, overwhelmingly located in Hawaii and California, when Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941.

The initial response of the American public after Pearl Harbor was somewhat muted. There were elements within the American government that did not desire to rush to judgement upon the loyalty of the Nisei, while focusing upon the threat from Imperial Japan. The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, sent the President a memorandum on the night of December 7, 1941, stating that the FBI had a list of 770 Japanese nationals who would be detained and questioned, with the appropriate authorization of the President. Hoover believed that the FBI and military intelligence agencies (which had cracked the Japanese code traffic) had enough knowledge of Japanese espionage operations within the U.S. to adequately handle suppressing the problem of spies, and the historical records supports this conclusion. Hoover did not believe that the Nisei should be interned, and as citizens were due Constitutional due processes. Indeed, a week after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt marked the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights with a public rededication to the ancient liberties which had been bequeathed by the Founders. With the country at war with Germany, Italy, and Japan, internment of enemy nationals and those with nationalist sympathies for the enemy was discussed briefly between Attorney General Francis Biddle and FDR; the president dismissed the Italians as “opera singers” but warned that the Germans might be an internal threat. However, with over 600,000 German nationals, plus approximately ten million Americans of German descent living in the country, internment posed a logistical problem which appeared insurmountable. The Japanese in America, however, were a much smaller, more managable number, and in their case two elements were to make a difference: public outrage and race.

The American public thirsted for revenge against the Japanese, and polls showed that the public favored a “Japan first” approach to the war. As Roosevelt and his military chiefs developed a “Germany first” strategy for victory in the overall war, this meant that immediate revenge against the Japanese would have to wait. Worse from the public’s point of view, Pearl Harbor marked the beginning of a sustained Japanese assault which would spread across southeast Asia unhindered for seven long months.

By February 1942, political pressures were reaching a new breaking point. Domestically the state of California was the focal point, as newspapers spread rumors of Nisei “fifth column” complicity with the enemy and editorialists harshly condemned the Japanese in round terms, while California politicians demanded that something be done to eliminate any perceived threat. Governor Culbert Olson and state Attorney General Earl Warren (who later became famous as a civil rights advocate upon the Supreme Court) worked closely with local law enforcement and politicians to build support for an evacuation solution. In Washington DC, both the Justice and War Departments were pressured to act by West Coast Congressmen who condemned the administration’s previous failure to deal with espionage and sabotage at Pearl Harbor, and was expected to take place in the future.

On February 15, 1942, a British army of over 100,000 surrendered the British stronghold at Singapore to a Japanese army about one-third of its size. The military situation in the American-held Philippines was deteriorating. On February 17, Attorney General Francis Biddle sent to President Roosevelt a letter in which he warned of the possibility of race riots within the western United States. Biddle had previously opposed internment and even mentioned the FBI’s position on internment, but Roosevelt was receiving conflicting advice from an institution which had a very different perspective on the Japanese and Nisei: the U.S. Army.

The U.S. Army had analyzed the potential loyalty of Japanese-Americans in Hawaii in the early 1930s, and had concluded in reports that the Japanese had uniquely retained a long cultural connection back to their homeland based upon racial identification and characteristics. The Army believed that this racial connection, supported by the Japanese schools, caused Japanese to “resist Americanization,” or assimilation into larger American society and culture. In the wake of Pearl Harbor and with a seemingly unbeatable Japanese Army now devastating southeast Asia, the Army’s viewpoint had hardened.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066 on February 19, 1942, in which he gave the War Department the authority to prescribe military zones within American territory, and then exclude “any and all persons” deemed to be threats. In the wake of the disaster at Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt could not afford another major event aided by espionage or sabotage, especially from within the U.S. Even if more moderate elements like the FBI or Biddle were correct that there was little threat from the Nisei, Roosevelt was not willing to be politically responsible in the event of another major Japanese surprise attack.

The issue was thus passed to the Western Defense Command, the service command in charge of defending the Pacific coastal regions. Lt. General John L. DeWitt of the WDC declared the entire state of California, the western halves of Washington and Oregon, and the southern half of Arizona as military zones in which all nationals or American citizens of Japanese ancestry were to be excluded. DeWitt had written to the Secretary of War, just days before Roosevelt signed the order, that the Japanese were a special case compared to Americans of German or Italian extraction: “In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.”

As a result, over 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry, including better than 70,000 American citizens, were given less than a month to dispose of their property and enter incarceration centers. Neither their property or civil rights were considered in this solution, and they were denied the due process of law in the determination of any individual threat or guilt.

Lt. General DeWitt in his final report on the internment operations (dated June 5, 1943) continued to use racism as the final justification for the operations: “It was impossible to establish the identity of the loyal and the disloyal with any degree of safety. It was not there was insufficient time in which to make such a determination; it was simply a matter of facing the realities that a positive determination could not be made, that an exact separation of the ‘sheep from the goats’ was unfeasible.”

As the hysteria slowly receded in the following years, releases of internees who clearly were not threats began. Many Nisei believed the best way to show their loyalty was to join the military, and in the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team young Japanese-Americans proved their loyalty to their nation in combat in Europe. Young Americans such as George Sakato and future U.S. Senator from Hawaii Daniel Inouye performed with extraordinary bravery, but full recognition of their deeds or the injustice done to the Nisei remained elusive in the atmosphere of the Second World War. In 1988, Congress voted a reparation payment to familial descendants of the Nisei for their property losses, and Sakato and Inouye were recognized for the Medal of Honor later in the 1990s. But in 1945, when the war ended, a majority of the Nisei remained in detention camps.

The National World War II Museum is charged with explaining to the American public why the war was fought, how it was won, and what it means to us today. The anniversary of Executive Order #9066 serves to remind Americans of our own moral limitations and challenges, and in so doing, hopefully also serves as a guide to Americans of the future for the people we should wish and strive to become.

Read additional posts about Japanese Internment.

Keith Huxen, Ph.D. is the Senior Director of Research and History at The National WWII Museum.

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags : Tags: 1942, Japanese Internment, Keith Huxen

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Leave a Reply