Posts Tagged ‘world war ii’

Howard and Jean Hart at the opening of Road to Tokyo.

A storied CIA operative, Howard P. Hart died recently at age 76. His connection to The National WWII Museum includes a substantial donation of wartime arms currently on display in multiple galleries on our campus, as well as two separate oral history interviews for our Digital Collections. The interviews, conducted by historian Tom Gibbs, covered Hart’s experiences as a child during the war while his family was held in a Japanese civilian incarceration camp in the Philippines. Now Museum Project Manager, Gibbs recalled meeting Hart for the first time in this post for the Museum blog:

I had the honor of sitting down with Howard Hart on a cold and snowy day in 2013 outside of Charlottesville, Virginia. When I arrived at his property, I did not know what to expect. What I did know was that I was about to meet someone extremely intelligent who had a heck of a story to tell about World War II. I was instructed by Mr. Hart to meet him at a post store—an old-timey general store that sold everything from wine to ammunition—at the base of the mountain where he lived. A white jeep stopped directly in front of me. A white-haired man in a low voice asked me for my identification. It was an unusual first step, and something that had never happened when I had interviewed other WWII veterans. I felt like I was in the middle of a Tom Clancy novel. When Mr. Hart determined that I passed muster, the warmest smile and greeting ensued, and I took a trip up the mountain to his famous home.

I knew Mr. Hart had a long and decorated CIA career, but the real reason I was there was to capture the story of the Los Banos civilian POW camp, and the incredible story of its liberation in 1945. The liberation coincidentally occurred on the same day the US flag was raised on Mount Suribachi, relegating it to back-page news. Over the course of three and half hours, Mr. Hart proceeded to tell me one of the most engaging and unbelievably human stories I ever captured on tape. Learning of the horrors of—and the actions required to survive in—a Japanese prison camp was humbling. It was his story of the camp’s liberation, however, that struck a chord with me, and it’s something I will never forget.

“I looked up, I had no idea what I was looking at,” he said. “I had never even seen a parachute before. It was as if some magical apparition was occurring in front of my eyes. And before I knew it, an American paratrooper was standing in front of me. He must have been 35 feet tall. He was angry and fired up and ready to kill Japanese. . . . This American paratrooper picked me up under his arm. It was a mile and half to the beach, and the entire time he told me, ‘Kid, I’m gonna get you home. Kid, I’m gonna get you home.’”

When 2,000 US civilian POWs who had been imprisoned since 1941 arrived in San Pedro, California, a band was waiting for them. “They had a band on the dock and they were playing the The Star-Spangled Banner,” he said. “I had never heard The Star-Spangled Banner before! We all wept. It was the most beautiful thing I ever heard, and I weep now telling this to you.”

Mr. Hart’s legacy lives on here at The National WWII Museum, both through his oral histories and his generous artifact donation, which allows our visitors to see top-notch examples of weapons used during the war. The 16 donated weapons, part of the Howard and Jean Hart Martial Arms Collection, are on display in The Duchossois Family Road to Berlin: European Theater Galleries, the Richard C. Adkerson & Freeport McMoRan Foundation Road to Tokyo: Pacific Theater Galleries, and The Arsenal of Democracy: The Herman and George Brown Salute to the Home Front.

From a grateful nation: Thank you, Mr. Hart.

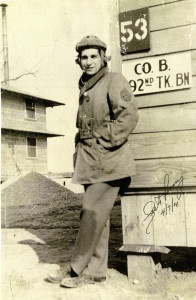

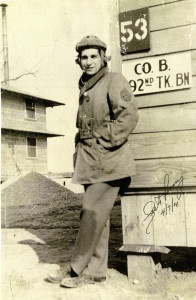

Lester Tenney during World War II.

Lester Tenney, a survivor of the Bataan Death March whose harrowing oral-history account of his ordeal as a WWII prisoner of war is an unforgettable component of The National WWII Museum’s Digital Collections, died Friday, February 24, in Carlsbad, California. He was 96.

Tenney’s postwar life was dedicated to education—both as a university business professor and as a staunch advocate for his fellow POWs in the quest for official acknowledgment by Japan of the wartime atrocities they endured. He was a regular speaker at the Museum, most recently capping the 2016 International Conference on World War II with a stirring presentation titled “The Courage to Remember: PTSD—From Trauma to Triumph.”

“He gave the speech of his life,” said Gordon H. “Nick” Mueller, PhD, the Museum’s president and CEO, in a message to his staff following news of Tenney’s death. “Lester’s DNA resides in this Museum.”

Tenney was tank commander with the 192nd Tank Battalion when he, along with 9,000 American and 60,000 Filipino troops, surrendered to the Japanese at the Battle of Bataan in April 1942. The ensuing Bataan Death March killed thousands during a 90-mile forced march to POW Camp O’Donnell.

“Number one, we had no food or water,” said Tenney in his Museum oral history. “Number two, you just kept walking the best way you could. It wasn’t a march. It was a trudge. . . . Most of the men were sick, they had dysentery, they had malaria, they had a gunshot wound.”

Their Japanese captors showed no mercy for the ill or wounded, Tenney said. “A man would fall down and they would holler at him to get up,” he added. “I saw a case where they didn’t even holler at him. The man fell down, the Japanese took a bayonet and put it in him. I mean, two seconds.”

Tenney’s march lasted 10 days. Conditions at Camp O’Donnell killed thousands more prisoners. Tenney survived that camp and others, passage to Japan in a “hell ship,” torture, and three years of forced labor in a coal mine before he was liberated at the end of the war. His WWII experiences, which he documented in a memoir titled My Hitch in Hell, haunted him all of his life.

“I feel guilty many times, even today,” Tenney said in his oral history. “I feel guilty that I’m back. I feel guilty that I’m living such a wonderful life. I feel guilty that a lot of my friends didn’t come back. Nothing I can do about it, but I can feel guilty because I feel that they were better than I was. I’m sure that my buddies who came back all feel the same.”

After the publication of his memoir in 1995, Tenney “shifted into a role as a prominent thorn-in-the-side of Japanese authorities unwilling or unable to acknowledge what had happened during the war,” said his obituary in The San Diego Union-Tribune. “Stories he shared with reporters, civic leaders, schoolchildren in the United States and Japan,” along with his published memoir, “eventually wrung apologies from government leaders and from one of the corporate giants that benefited from POW slavery.”

Tenney is survived by his wife of nearly 57 years, Betty, a son, two stepsons, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Our deepest condolences go out to his family, friends, and fellow WWII veterans. Our gratitude for Lester Tenney’s service and sacrifice—and for his decades of dedication to ensuring that his wartime experiences and those of his fellow POWs would not be forgotten—lives on.

Lester Tenney’s oral history is part of The National WWII Museum’s Digital Collections.

State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda

Dear Friends,

News of the opening of “State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda,” a powerful exhibition created by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, has already generated some passionate conversation on social media.

We’re honored to be hosting this thought-provoking exhibition, which was created in 2009 by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and has been displayed in other great institutions around the country, including the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and, most recently, the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin, Texas. State of Deception is a historical study of propaganda, and poses questions about the power of communication and the importance of mindful media consumption. Some have asked if the Museum timed the exhibit to coincide with the current political climate. We did not. In fact, the exhibition has been scheduled since January 2015, and was created by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum before that—in 2009. However, we know that the tone of the recent election and other current events have heightened sensitivity to this subject matter.

Please note that the exhibit itself (which predates the recent election by seven years) does not have any political agenda. Nor does the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum or The National WWII Museum. Rather, the exhibition’s goal is to raise questions about the power of propaganda and to encourage people to think critically about the messages they receive. It’s exciting to see that the exhibit is already striking a chord with so many.

We encourage you to visit the exhibition while it’s in residence at the Museum (through June 18) or experience it virtually via the links presented below to form your own opinions. On Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, we’ll share the latest news about the exhibit and surrounding programs, and we hope you’ll Like and Follow us to hear the latest. These channels are also a wonderful forum for discussion and we welcome your engagement! However, in order to ensure that the conversation remains welcoming to all who view our posts—including people of every political stripe as well as school groups, veterans and their families, Museum visitors, and more—we ask that all commenters on these channels remain mindful of the educational intent of these posts, and respectful of the community receiving them.

To that end, please pause before posting to consider the following social media guidelines, modeled on the guidelines used by our friends at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to encourage an engaging, inclusive dialog.

Social media guidelines:

The goal of our social media platforms is to share news of The National WWII Museum and World War II, and secondarily offer a forum for conversation and feedback about our posts. We reserve the right to remove posts and comments that violate these guidelines:

— Comments should be relevant to the post’s topic.

— Courtesy is essential. Comments with vulgarity, threats, or abuse aimed at others are not acceptable.

— Comments are an appropriate place to question or disagree with ideas and opinions, but not make attacks against groups or individuals.

— Comments that share misleading or historically inaccurate information will be deleted.

Thank you for your thoughtful consideration of the above guidelines, and thank you for your continuing support of The National WWII Museum.

Our social media channels:

Facebook: Facebook.com/WWIIMuseum

Twitter: @WWIIMuseum

Instagram: wwiimuseum

State of Deception links:

Find a listing of all of the public programming scheduled for the exhibition here.

Find the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s main site for the exhibition here.

Find the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s accompanying educational site here.

Watch a live walk-through of State of Deception with United States Holocaust Memorial Museum educator Sonia Booth here.

Stream the January 26 opening reception for the exhibition here.

Watch a Lunchbox Lecture by Assistant Director of Education Gemma Birnbaum about propaganda specifically aimed at the youth of Nazi Germany here.