WWII Yearbooks Lead to Path of Discovery

- The inside cover from the 1944 edition of Sealth, the yearbook of Seattle's Broadway High School. Collection of The National WWII Museum.

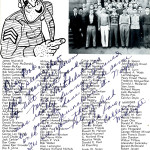

- This page from the 1944 Broadway High School yearbook lists the many seniors who have joined the military. Collection of The National WWII Museum.

- The cover of the 1944 issue of Sealth, the yearbook of Seattle's Broadway High School. Collection of The National WWII Museum.

In this guest blog post, middle school teacher Tamara Bunnell, a participant in The National WWII Museum and Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History’s Story of World War II summer teacher seminar, discusses how one Museum artifact led her to uncover the WWII history of Japanese Americans from her community.

In September of 1941, a young woman named Louise Tsuboi smiled for her final yearbook photo. It was her senior year at Seattle’s Broadway High School (BHS), and she must have been excited as she looked ahead to the school year to come. Aside from Broadway’s outstanding classes, there would be dances, academic achievements, clubs, and activities. For Louise, that meant time with Science Club, the Honor Society, and the Nichibei Japanese American Choir to name a few. Months later, her photo appeared in the senior section of the BHS yearbook, where each page of the student-designed publication was captioned with a phrase related to graduation. Some were comical (“For Whom the Bell Tolls” and “Never Come Back”) and some sentimental (“Outward Bound” and “Beyond the Horizon”). Topping Louise’s page was the phrase, “Made in America.”

Louise was no longer at Broadway High School when the yearbook was released, so she wasn’t there to see her photo or the title, though she most certainly would have noted the irony. Like every other student of Japanese descent at BHS, even those “Made in America,” Louise had been removed from her home and sent to a temporary holding center in nearby Puyallup, Washington. Clumsily and hastily built on land normally used as fairgrounds, “Camp Harmony” was where she and her classmates would be temporarily held before being sent on to more permanent incarceration camps for the duration of the war.

As a Seattle resident and teacher of Pacific Northwest History, I have long been interested in the story of Broadway High School, which was located just a few blocks from where I teach. However, it wasn’t until I attended a WWII-focused Gilder-Lehrman summer seminar for teachers at The National WWII Museum that I came to study the yearbook that would lead me to Louise’s story. While there, in addition to having the opportunity to tour the museum and attend lectures with noted historian Dr. Donald L. Miller, we were asked to build a lesson plan on something from the Museum’s collections. To help us get started, the Museum’s education and curatorial teams put together a room of artifacts related to our interests and curricula and also directed us to their online resources. Pouring over them and fascinated by each one, I thought I would never be able to choose until I came across something from home in the Museum’s digital exhibit, “See You Next Year: High School Yearbooks from WWII.” It was the 1944 edition of Sealth, the Broadway High School yearbook.

Though it likely came out some time close to D-Day, there are only a few references to the war in the book. One war-related section, a two-page spread listing the names of alumni serving in the war, is arresting. Over 500 names grace the page, and each has a story. There is Robert Dorwart, who floated for 16 days in the Pacific after his B-17 was shot down, famed sculptor George Tsutakawa, who served as a translator in the Military Intelligence Service despite the fact his own family was incarcerated at Tule Lake, and Leo Sarkowsky, whose Jewish family fled Germany and landed in Seattle by way of Czechoslovakia, and whose brother Herman, also a WWII veteran, would go on to found the Seattle Seahawks.

As interesting as I found the 1944 yearbook and the people in it, however, I knew there was another story to discover about the people who were not. Seattle, like most west coast cities, had a sizable Japanese American population before the war. Though the 1882 federal Chinese Exclusion Act, restrictive housing covenants, and other formal and informal discriminatory policies limited the freedoms of Japanese Americans, their presence and influence in the city was significant. I wanted to know just how significant the population was at BHS, so upon my return to Seattle I contacted the school’s alumni association to learn more. Broadway High closed not long after WWII ended, but their alumni association has maintained a continuously updated archive since that time. It is a treasure trove of information featuring a veritable who’s who of Seattle history, lovingly maintained by the school’s graduates who have remained connected to this day. There I was able to borrow a set of WWII-era yearbooks, and through them I learned that my suspicions were correct: the BHS student body was significantly different in 1944 than it was before Pearl Harbor and the ensuing Japanese Incarceration.

How significant? The pre-incarceration Broadway student body was approximately 30% Japanese American, and the earlier editions of Sealth make the contributions of those students clear. They are valedictorians, class officers, all-star athletes, newspaper editors, and thespians. They brought their culture to the school through the Nichibei Choir and through tea ceremonies at the student carnival, yet in most ways little in the yearbooks distinguishes them from their classmates, many of whose parents and grandparents were also immigrants to the United States. On Louise’s page of the 1942 yearbook, seven of the 17 students have Japanese names. Like Louise, unless their families were able to move away from the West Coast before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, they were almost certainly removed from their homes in the spring of 1942 and sent to Camp Harmony with only what they could carry.

The devastating impact of this removal on the Japanese American community is obvious and well documented. At Broadway, the larger school community was affected as well. Members of the faculty traveled to Camp Harmony to conduct a graduation ceremony for the students there, and many BHS students made the effort to write to and visit their Japanese American friends. I’ve heard stories of students driving down from Seattle to toss what they could over the fences to their former classmates, including clothing, books, and toiletries, though all but the letter writing ended when the residents were sent on to permanent camps further inland. Like many Seattle residents, Louise and her family were sent to Camp Minidoka in Idaho.

Among the other residents at Minidoka was the man who would become Louise’s husband of more than 50 years, Shiro Kashino. A scrapbook housed today at Seattle’s Nisei Veterans Memorial Hall contains a hand drawn dance card Shiro made for Louise, though their dancing time together would be halted for a time by Shiro’s decision to leave the camp and join the famed Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat team. Shiro would go on to become one of the most decorated and respected members of his regiment, and his story is a fascinating one. So fascinating, in fact, that it has been featured in a recently published graphic novel, Fighting For America: Nisei Soldiers, by Lawrence Matsuda and Matt Sasaki. Shiro’s chapter has also been turned into a short animated film, which can be seen here. Both the book and film are excellent resources for any teachers and students interested in WWII.

I plan to use both, as well as the 1942 and 1944 Broadway High School yearbooks, in my classroom this year when my students study World War II and the Japanese Incarceration. I will use the yearbooks as comparative primary sources through which my students can discover this history themselves, a history that is immediate and local while also addressing the larger themes of patriotism, loyalty, and social justice. Sometimes, it seems, you must travel to another place in order to discover the history of your own neighborhood. Many thanks to The National WWII Museum and the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History for leading me down this path.

Posted by Tamara Bunnell, who teaches seventh grade humanities with a focus on Pacific Northwest History at The Northwest School in Seattle, Washington.

Leave a Reply