SciTech Tuesday: Niels Bohr announces fission of uranium

Yesterday was the 75th anniversary of the 5th Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics. This meeting on the 26th of January 1939 may seem an obscure point in history. Fifty-one physicists from around the world gathered at George Washington University, which co-sponsored these conferences with the Carnegie Institute. A statement published in Science on the 24th of February 1939 contained this paragraph:

“Certainly the most exciting and Important discussion was that concerning the disintegration of uranium of mass 239 into two particles each of whose mass is approximately half of the mother atom, with the

release of 200,000,000 electron-volts of energy per disintegration. The production of barium by the neutron bombardment of uranium was discovered by Hahn and Strassmann at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute in Berlin about two months ago. The interpretation of these chemical experiments as meaning an actual breaking up of the uranium nucleus into two lighter nuclei of approximately half the mass of uranium was suggested by Frisch of Copenhagen together with Miss Meitner, Professor Hahn’s long-time partner who is now in Stockholm. They also suggested a search for the expected 100,000,000-volt recoiling particles which would result from such a process. Professors Bohr and Bosenfeld had arrived from Copenhagen the week previous with this news, and observation of the expected high-energy particles was independently announced by Copenhagen, Columbia, Johns Hopkins, and the Carnegie Institution shortly after the close of the Conference. Professors Bohr and Fermi discussed the excitation energy and probability of transition from a normal state of the uranium nucleus to the split state. The two opposing forces, that is, a Coulomb-like force tending to split the nucleus and a surface tension-like force tending to hold the “liquid-drop” nucleus together, are nearly equal, and a small excitation of the proper type causes the disintegration.” (Science, vol 89 number 2304, page 180)

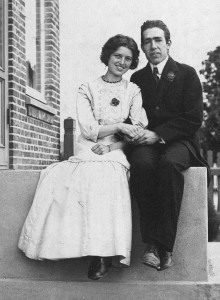

It could be argued that this was the starting point of the Manhattan Project. Niels Bohr, the winner of the 1922 Nobel Prize for his work on atomic structure, spoke about the the first observed, and explained, observation of nuclear fission. Enrico Fermi, who had won his Nobel Prize just a few months before, was there to discuss this announcement.

Three and a half years later, Fermi would build a reactor under the football field at the University of Chicago and create the first sustained chain reaction of uranium fission, and be a primary scientist in the Manhattan Project. Fifteen months later Bohr was under Nazi rule in occupied Denmark—he escaped the Nazis in dramatic fashion in September 1943 when he learned they had plans to arrest him, and left on a fishing boat for Sweden. From Sweden he went to England, where he joined the Tube Alloys project. In December of 1943, under the alias of Nicholas Baker, he traveled to the US to meet with Gen. Groves, and scientists at Los Alamos.

Over the next two years Bohr traveled frequently to Los Alamos, where he acted as a mentor to the young scientists, much as he had in the years before the war at his institute in Copenhagen.

Niels Bohr was a brilliant and fascinating man. He risked his life to save others, working for years to get scientists and technicians of Jewish ancestry out of Europe. He developed a model for the structure of the atom, and when it was surpassed, said “there is nothing else to do than to give our revolutionary efforts as honourable a funeral as possible.” He was a scientist who could see past his own ambitions and accomplishments, and helped develop a community of colleagues whose collaboration exceeded their individual efforts.

After the war, Bohr returned to Copenhagen and ran the institute which now bears his name-The Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen. He won the Atoms for Peace award in 1957 for his efforts to build an international agency on atomic weapons and energy. He died in 1962, at age 77.

.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum

Leave a Reply