70 Years of the K-9 (Canine) Corps

Dogs have been used in times of war even before the invention of gunpowder. Romans used them to charge into battle and attack the enemy. Native Americans used them as both pack and draft animals as well as sentry animals. Even in the Middle Ages, dogs were sent into battle equipped with their own armor. Modern European societies had long established traditions of using dogs in war. Many dogs were used throughout World War II by the French, the Belgians and by the Germans as messengers, medics, and pack animals. The US, however, never had a war dog program of this type. The only working dogs in the US military at the start of World War II were sled dogs used in Alaska when the snowy and icy terrain was impassable by vehicle. It was through the forward thinking of some in the US military and the enthusiastic support of dog fanciers that the US military began to undertake a war dog training program. Dog fanciers and these military men envisioned the various ways that dogs could be useful in both combat and non-combat roles.

Advocates for the use of dogs were quick to point out the many characteristics that made dogs useful in war. First of these is a dog’s respect of humans. Good dogs are always eager to please their masters. This means that with the right intelligence level, they can become highly trained. Dogs are also docile and watchful by nature. Although a dog’s eyesight is not particularly acute, their ability to perceive movement is exceptional. They have acute senses of hearing and smell and can act with great speed, making them exceptional companions in times of war. This watchfulness and docility, combined with acute senses, grants them an extraordinary ability to observe, find, and notice many things a human cannot.

In January 1942 Dogs for Defense, Inc. (DFD) was established as a national organization to help procure dogs for war training purposes. Although some dogs were acquired through purchase, it was largely through the dog owner population’s patriotic sentiments that most dogs were acquired for training. It was the job of DFD not only to procure the dogs, but also to train them. Trained dogs were to be given to the Quartermaster General, who then turned them over to the Plant Protection Branch and Inspection Division. Many thought the primary use of dogs would be as sentries for civilian war plants and quartermaster depots.

Clyde Porter gives his dog Junior to Dogs for Defense. Courtesy of the National Archives.

On March 13th 1942, the efforts of DFD and the war dogs being trained were officially recognized by Colonel Clifford C. Smith, chief of the Plant Protection Branch of the Quartermaster Corps. By the autumn of 1942, the war dog training program had become commonly known as the “K-9 Corps.” The army soon made the title official, designating the unit the “K-9 (Canine) Section.” Other possible designations were “WAGS” or “WAAGS,” but luckily many felt the name too wimpy for the feats they would be asked to do. The Marine Corps liked to call their war dogs “Devil Dogs.” The US Marine Corps initially had a preference for male Doberman Pinchers, and so these dogs became synonymous with the Marines. The “Devil Dog” title was apt since they were well-known for their fighting tenacity.

To meet the demand for war dogs and to systemize the dogs’ training, the Quartermaster Corps soon took over the training of the dogs and their handlers. They trained over 10,000 dogs, most of which were used on the Home Front for sentry duty. However, more than 1,800 dogs were sent into combat starting in 1942. The US Marine Corps sent over 1,000 dogs to be trained at their Camp Lejeune facility. However, many commanders were unfamiliar with war dogs and how to use them to their advantage. Seven Quartermaster Corps (QMC) War Dog Platoons were sent to the European Theatre of Operations, but they did not have much success. In 1943, the QMC sent a detachment of six scout dogs and two messenger dogs to operate in the Pacific Theatre as a test of their value in combat conditions.

Japanese troops were deeply entrenched on many islands in the Pacific theater of operations. Thousands of Japanese soldiers were hiding in caves and in the dense jungles. These troops would lie in wait for patrolling Marines and soldiers and then ambush them before the troops ever detected enemy forces. One of the first tests of war dog platoons took place on the Pacific island of New Britain. Here Marine war dogs attached to the Sixth Army first worked on sentry duty, but once a beachhead was established the dogs and handlers began conducting patrols. They went on forty-eight patrols in fifty-three days while on the island. These patrols accounted for 200 Japanese soldiers being captured or killed. This early success of war dog platoons set the standard for what could be expected, and what could not, from a K-9 detachment.

The newness of the war dog program meant there were many hurdles for the Army, the handlers, and the dogs to overcome. One of the largest obstacles for dogs and their handlers was that infantry commanders often lacked an understanding of how best to use war dogs. This meant that war dog platoons could not always meet their full potential. A vital element to the success of war dog platoons was in the communication between war dog platoon commanders and the commanders of ground troops. Ground commanders needed to know what a dog could and could not be expected to do. Dogs and handlers were often sent into areas where their skills could not be used effectively.

There were some things only experience could teach, and the Army itself had to adapt its training methods to lessons learned in the field. At first, no one accounted for wind direction and velocity, heat and humidity, and the concentration of human scents as factors affecting a dog’s ability to alert to enemy soldiers. There was also an idea among many that the dogs were indefatigable, but in reality, dogs needed rest just like soldiers. Dogs that are tired lose interest in working and their senses become compromised. It was important for handlers and commanders to make sure dogs were given rest time. As handlers learned when their dogs were and were not able to work effectively, they were able to communicate this to their commanders.

Between the Army and the Marine Corps, over 10,000 dogs were trained for war, and nearly 2,000 dogs were sent overseas. Dogs proved to be an invaluable resource in the Pacific and on the Home Front. When these dogs were recruited, their owners were promised that if the dogs survived the war, they would be returned to them. The military’s promise was difficult to fulfill. The US military did not anticipate the thousands of hours of retraining and the cost that such a promise would require. But through the work of Lt. William Putney and Major Harold C. Gors, dogs were given demilitarization training and sent home.

In World War II, the War Dog Training Program was new, untested, and groundbreaking. The insights and knowledge gained from large scale training and intense combat experience would allow the K-9 Corps to flourish in postwar America. The success of dogs in military, police and humanitarian roles is due to those dogs of World War II that embarked on a journey to unknown territory and became warriors and heroes.

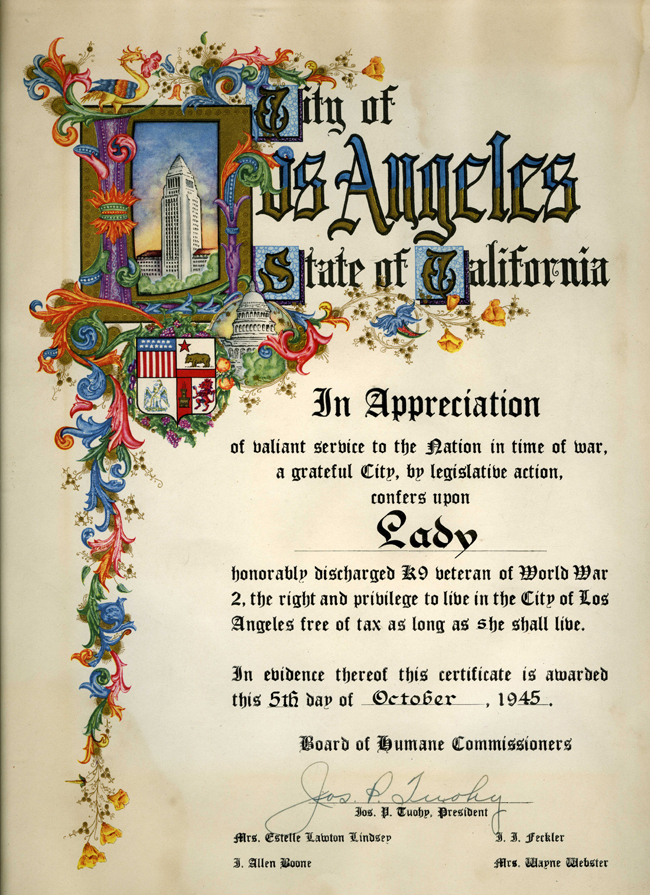

Certificate of Appreciation for Lady from Los Angeles, California, for her service as a war dog. The National WWII Museum, Inc., 2008.285

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags : Tags: Animals in WWII, dogs

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Leave a Reply