Posts Tagged ‘penicillin’

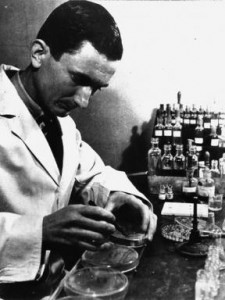

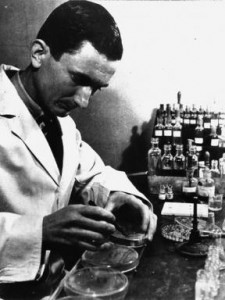

Sir Howard Florey, Nobel Prize in Medicine 1945. Image courtesy of the Nobel Foundation.

Today marks the birthday of Howard Walter Florey, the Australian pathologist instrumental in developing penicillin as a drug for human use. Florey led the team of Oxford scientists that purified penicillin, researched its antibacterial properties and conducted clinical trials. He shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming.

Working under the constant fear of air raids and a serious lack of funds and equipment, Florey and his team recognized the military importance of combating disease and infection as World War II raged in Europe. As the Battle of Britain began, the Oxford scientists devised a plan for a potential Nazi invasion. Florey’s team resolved to destroy their work rather than allowing it to fall into the hands of the enemy. But not all would be lost; they rubbed the spores of the precious strain of the penicillin-producing mold into their lab coats where it could lie dormant for years. If Florey and his team were forced to flee, they could easily escape with years of research hidden on their backs!

Oxford was spared and the spore-laden coats were not needed. Florey’s leadership led to the development of the drug for mass production for both military and civilian use and to date, antibiotics have saved millions of lives. Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies stated, “in terms of world well-being, Florey was the most important man ever born in Australia.”

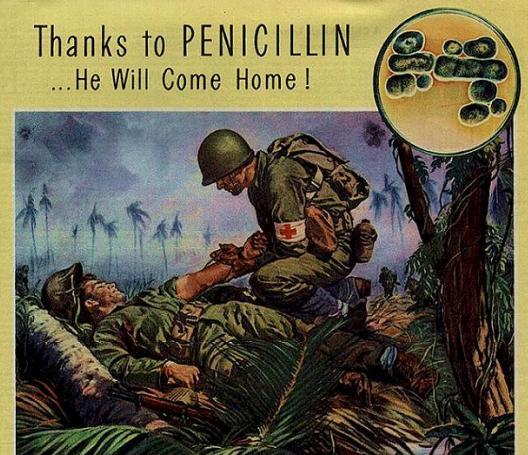

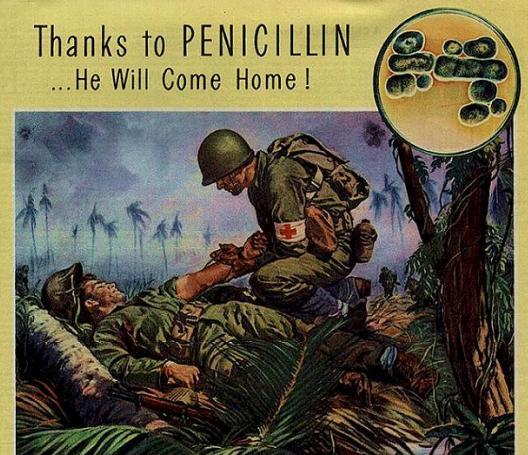

Learn more in our lesson, Thanks to Penicillin… He Will Come Home!

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator

Related Posts: Penicillin

In June of 1943 Mary Hunt, a lab assistant working in Peoria, Illinois, found a cantaloupe at a local market covered in mold with a “pretty, golden look.” This mold turned out to be a highly productive strain of Penicillium chrysogeum and its discovery marked a turning point in the quest to mass produce penicillin.

In June of 1943 Mary Hunt, a lab assistant working in Peoria, Illinois, found a cantaloupe at a local market covered in mold with a “pretty, golden look.” This mold turned out to be a highly productive strain of Penicillium chrysogeum and its discovery marked a turning point in the quest to mass produce penicillin.

During the first half of 1943, American pharmaceutical companies made 400 million units of penicillin – enough to treat approximately 180 severe cases of infection. During the second half of 1943, 20.5 billion units were produced. By D-Day on June 6, 1944, production increased to a staggering 100 billion units per month. Thanks to one very special summertime cantaloupe, penicillin quickly became a “miracle drug” saving countless lives from once deadly infections.

Check out our Penicillin Lesson Plan to learn more about the Allied effort to mass produce penicillin.

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator

Advertisement for penicillin production from Life magazine, August 14, 1944.

The final posting in a three-part series exploring the development and mass production of penicillin.

Reports of Howard Florey and his team successfully treating bacterial infections in mice drew great interest from both scientific and military communities. World War II was well underway in Europe and the ability to combat disease and infection could mean the difference between victory and defeat. Because British facilities were manufacturing other drugs needed for the war effort in Europe, Florey and his colleague, Norman Heatley, travelled to the United States in July of 1941 to continue research and seek help from the American pharmaceutical industry. They convinced four drug companies, Merck, E. R. Squibb & Sons, Charles Pfizer & Co. and Lederle Laboratories, to aid in the production of penicillin.

Florey and Heatley ended up in Peoria, Illinois, to work with researchers who had perfected the fermentation process necessary for growing penicillin. The researchers in Peoria used corn instead of glucose, or simple sugar, as the nutrient source, and the penicillin grew approximately 500 times more than it had in England. The team searched for more productive strains of Penicillium notatum, finding the best specimen growing on an over-ripe cantaloupe in a Peoria grocery store.

Meanwhile, penicillin was used to cure the first human bacterial infection, proving to researchers the vital importance of the drug to save lives. But, that one cure used up the entire supply of penicillin in the entire United States! Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it was clear to scientists and military strategists that a combined effort was needed to produce the large amounts of penicillin needed to win the war. A total of 21 US companies joined together, producing 2.3 million doses of penicillin in preparation of the D-Day invasion of Normandy. Penicillin quickly became known as the war’s “miracle drug,” curing infectious disease and saving millions of lives.

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator

Part two of a series on the development and mass production of penicillin.

Sir Alexander Fleming receiving the Nobel Prize from King Gustaf V of Sweden. Howard Florey (far left) and Ernst Chain (second from left) shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Fleming.

In 1945, Sir Alexander Fleming, Ernst Chain, Sir Howard Florey were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases.” During his Nobel lecture, Alexander Fleming applied natural selection to the simplest living things on earth. He predicted that penicillin would be used carelessly and over time become less effective at killing bacteria, a phenomenon called antibiotic resistance. Fleming said, “There is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.”

Natural selection, introduced by Charles Darwin in 1859, is the gradual process by which the frequencies of traits in a population change over time. Darwin, whose 204th birthday is today, proposed that all living things vary, that variations either increase or decrease survival, and that surviving organisms will pass their traits on to offspring. Some bacteria can produce enzymes which break down antibiotics while others can make proteins that work as pumps to remove antibiotics from the cell. The misuse of antibiotics mentioned by Alexander Fleming in his 1945 lecture, selects for resistant bacteria to survive, reproduce, and pass on resistance to future generations.

Next week, Florey and Heatley travel across the Atlantic to team up with the U.S. pharmaceutical industry.

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator

Part one of a series on the development and mass production of penicillin.

Norman Heatley working with Penicillium cultures. Photograph William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford.

The development of penicillin as an antibiotic began with Sir Alexander Fleming’s famous discovery in 1928. While Fleming’s serendipitous discovery is the stuff of microbiology legend, the work of a lesser-known team of scientists working in Britain is often left out of the story of penicillin. Beginning in 1938, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain began transforming the Penicillium “mold juice” into a medicine suitable for human use. The laborious task of purifying and concentrating penicillin was improved when their colleague Norman Heatley adjusted the pH of the solution. Heatley developed an assay (a method of quantitatively measuring the active ingredient in a sample) to improve the stability of penicillin in order to isolate the drug. He even automated the process of extracting penicillin by building a device with milk churns, bottles, and yards of rubber tubing.

To their great excitement, Florey’s team successfully cured Streptomyces pyogenes infected mice with penicillin on May 25, 1940. Norman Heatley oversaw the trials and recorded in his diary, “After supper with some friends, I returned to the lab and met the professor to give a final dose of penicillin to two of the mice. The ‘controls’ were looking very sick, but the two treated mice seemed very well. I stayed at the lab until 3:45am, by which time all four control animals were dead.” Delirious with excitement, Heatley returned home early that morning, surprised to find that he had put his underpants on backwards in the dark! The usually mild-mannered Heatley noted in his journal, “It really looks as if penicillin may be of practical importance.”

Next week, Sir Alexander Fleming, Charles Darwin, and antibiotic resistance.

Post by Annie Tête, STEM Education Coordinator

In June of 1943 Mary Hunt, a lab assistant working in Peoria, Illinois, found a cantaloupe at a local market covered in mold with a “pretty, golden look.” This mold turned out to be a highly productive strain of Penicillium chrysogeum and its discovery marked a turning point in the quest to mass produce penicillin.

In June of 1943 Mary Hunt, a lab assistant working in Peoria, Illinois, found a cantaloupe at a local market covered in mold with a “pretty, golden look.” This mold turned out to be a highly productive strain of Penicillium chrysogeum and its discovery marked a turning point in the quest to mass produce penicillin.