Oral History Spotlight – Ted Paluch, Malmedy Massacre Survivor

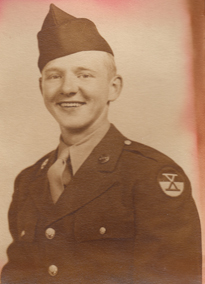

Ted Paluch, 1943

Theodore “Ted” Paluch was born and raised in the “City of Brotherly Love” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to a small family. Ted followed the war in Europe closely and thought that the United States might eventually get involved. “We used to gather round the radio or read the extras from the paper to follow the war. We knew what was going on.” Paluch recalls. Ted was playing pinball on Sunday December 7, 1941 when he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor from a friend. Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor Ted Paluch decided that he should join the United States Marine Corps. “I went downtown to join the Marines and they turned me down! I didn’t want to join the Navy so I decided that I would wait until they drafted me.” Ted didn’t have too long to wait, in January 1943 he received his draft notice and was inducted into the US Army. Paluch said, “When I was inducted into the Army I was excited. When you’re young you figure that you will do all the shooting…well it turned out a little different.”

“We had maneuvers in Louisiana and on our first maneuver my unit; Battery B 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion was captured. That was a bad omen. After that I figured that I might be captured if and when I ever went overseas. I really don’t know why I thought that, but I had a bad feeling.” Ted and the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion shipped overseas to Europe in August 1944. “My first taste of war was when one of the German U-boats sunk one of the ships in our convoy. They hit a tanker and it was ablaze. That’s when I realized that I was really at war.”

Paluch’s battalion first saw action in the Hurtgen Forest just prior to the Battle of the Bulge. As Ted explains it, “We were in the Hurtgen for a while, that was a bitch I’ll tell you. The damn trees would explode from the German artillery, and in just a matter of days it seemed that every tree within sight was stripped bare of all limbs. It was a bloodbath in there.” As bad as the Hurtgen was for Paluch, the worst was yet to come.

On December 16, 1944, the German Wehrmacht unleashed Operation WACHT AM RHEIN and attacked the US Army through a small, dark, dense forest that stretches between Belgium and Luxembourg known as the Ardennes. The surprise German Offensive, which is popularly called “The Battle of the Bulge”, rapidly gained ground and by the end of the day on the 16th many US units were in full retreat.

Shortly after being pulled out of the Hurtgen Forest and before the German attack Paluch and the 285th were sent to Schevenhutte, Germany to garrison the town. On December 16 the unit was given orders to proceed from the Seventh Corps to St. Vith and join the Eighth Corps. “We left Schevenhutte early in the morning on the 17th of December and were heading in the direction of Malmedy. I remember that it was wet, foggy, and damn cold. It wasn’t snowing yet, but I remember it being very cold.” The column of vehicles that encompassed Battery B of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion was a column of about 30 vehicles and roughly 140 men. As Paluch’s column neared Malmedy it went down a road and through the small crossroads town of Baugnez, Belgium. As the column went through the crossroads it came under fire from several German vehicles and tanks approaching from another road. These German vehicles were the lead elements of Kampfgruppe Peiper, the spearhead of the German attack in the Northern Ardennes. Paluch recalls, “The lead vehicles in our convoy were fired on. The lead vehicles were way ahead of us and the Germans were still a good bit away from them, so when they were fired on the lead vehicles had a chance to run and get out of there, which they did.”

As the lead vehicles sped away and out of harm’s way the after part of the column came under fire from the rapidly approaching SS tanks. “I saw them coming and our column stopped. I jumped out of the truck and into a ditch full of icy cold water. All I could hear was firing. I popped my head up to see and all I could see was tracers, I never saw so many tracers in my life. I pulled my head back down as a tank rolled around the corner and came towards us. I could see that the men in the tank and the troops with them were SS troopers. They had the lightning bolts on their collars. All we had was carbines and here was this tank coming down the road right at us. As it got close to us it leveled its gun at the ditch and the tank commander told us to surrender. What were we going to do? I threw my carbine down and threw my hands up.”

Immediately after surrendering Paluch was taken captive by two SS troopers who thoroughly searched him and sent him down the road with some other members of his column to the crossroads and into a field. While there the SS troopers searched them again and took anything that they could use from the prisoners. Ted says of his captors, “I had socks, gloves, and cigarettes, anything of value they took. The guys that captured us were young, they seemed like ok guys. They didn’t mishandle us or rough us up, they simply took us prisoner, searched us and then moved on. They were combat troops and didn’t have time to mess with us POWs. The guys that captured us and the tanks that were with them stayed around for about ten minutes and then disappeared. We were standing there in the field with our hands up not knowing what was coming. I could hear guys praying, maybe I was too…you know…you could hear it, all you could think of was getting away.”

As the initial SS troops pressed forward the rear echelon infantry came into view and began to pass the large group of American prisoners standing in the open field at the crossroads of Baugnez. “One of the vehicles came around the corner and started firing into our group. I don’t know who the hell it was, or why they started firing but they did. We were standing there with our hands up and I was in the front of the group nearest the crossroads. As the German tanks passed they fired into the middle of the group of us, everybody started to drop and I dropped too. I got hit in the hand as I went down. After that as each vehicle passed they fired into the group of us laying there dead or dying in the field. Anyone that was moaning they came around and finished them off. After that they went back and took off. After laying there for I guess an hour or more I heard a voice I recognized yell, ‘Let’s go!’, so I got up and ran down a little road towards a hedgerow. The Germans came out of the house on the corner and took a shot at me and I dove into a hedgerow. I had some blood on me and I lay down in the hedgerow. I heard one of them come running towards where I was laying and look me over, I could feel that guy standing above me, he could have shot me in the back and gotten it over with, but he didn’t. I knew he was waiting for me to move but I just laid there…dead still.”

Paluch lay in the hedgerow for a short while, stuck his head up and saw no one, rolled down the hedgerow and crawled along a railroad line that happened to take him to Malmedy. Ted continues, “Along the way I met a couple of other guys from my unit who had survived. We all came into Malmedy that night together.” While in Malmedy, Paluch’s wound was tended to, he was interrogated by Intelligence and within two weeks he was back with the remnants of the 285th back in action in the Ardennes.

The aftermath of the infamous Malmedy Massacre.

“I never tried to think about the Massacre too much after the war. I tried to put it behind me, but it never really has been behind me, it’s hard to forget. I don’t know if we would have done that, but I don’t really hold any animosity towards them, I wish it didn’t happen but it did. A soldier gets orders just like we do and you carry them out. It’s a hell of a thing, but its war.” When asked if the memories of the Massacre affect him today, Ted’s eyes grew misty and his chin began to quiver as he said, “I lost a lot of good friends that day, I knew almost every one of those guys who were killed that day. I’m lucky…all my friends…all those young guys, they were all my age, with their whole life ahead of them. It never should have happened, and I hope no one ever forgets that it did.”

Ted Paluch (center) and fellow survivors of the Malmedy Massacre, 1945

Word of the massacre spread rapidly through American lines and helped to strengthen the American resolve to stop the German Offensive dead in its tracks. The Battle of the Bulge officially ended on January 25, 1945 when American forces pushed the Germans back to their original pre-December 16 lines. More than 1,000,000 American servicemen fought in the Battle of the Bulge making it the single largest battle ever fought by American troops. More than 83,000 Americans were casualties of the fighting. The victims of the Malmedy Massacre lay undiscovered and frozen until January 14, 1945, when American troops recaptured the area from the Germans. After the war, Jochen Peiper and many of his men were tried for war crimes as a result of the Malmedy Massacre. The trial prosecuted more than 70 persons. Of those 70, there were 43 death sentences issued (although none were carried out) and 30 lesser sentences.

Ted Paluch was interviewed at his home in Philadelphia by Manager of Research Services Seth Paridon on October 20, 2009.