Manhattan Engineer District Established

The Manhattan Engineer District was the code name for the Army elements involved in the larger Manhattan Project. The project had its beginnings in 1939, with several respected physicists including Albert Einstein urging President Roosevelt—via the so-called Einstein-Szilárd letter—to consider the reality of the dangers of atomic power. They feared that Nazi Germany would develop such a weapon, and hoped to be allowed to research atomic power themselves and develop a weapon first. Roosevelt heeded their warnings, and immediately set up an advisory board to delve deeper into the issues raised.

The project was supported by Canada and the UK in addition to the US. All had a stake in its outcome and provided manpower and support for the production of atomic weapons. The Maud Committee in Great Britain had been doing its own independent research until joining up with the American initiative in 1941. That relationship, however, was never a comfortable one and the flow of information from country to country was essentially censored.

On 13 August 1942, the Army component of the project was officially activated and code-named the Manhattan Engineer District under the command of Col. James Marshall initially, and later Gen. Leslie Groves. The origin of the name came simply from the fact that Marshall worked out of Manhattan, and the bland name wouldn’t suggest the true, top-secret nature of the project.

The project had dozens of components, with sites in more than a dozen locations around North America. Those at Oak Ridge, Tennessee worked mainly with uranium. The actual design and research labs were located at Los Alamos, New Mexico. The first fruit of their labor was the successful Trinity Test in August of 1945. President Truman approved the use of the bombs, which were subsequently dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Though Truman believed he would ultimately be saving lives by forcing an end to the war in the Pacific, his decision remains highly controversial to this day.

The Manhattan Project employed more than 100,000 personnel and cost $2 billion dollars, or approximately $24 billion by today’s standards. The project only ceased to exist with the creation of the US Atomic Energy Commission in 1947.

- Army Air Corps Capt. David Semple flew several of the more than 150 test flights performed as part of the Manhattan Project, and was responsible for training the bombardiers who completed the atomic missions. Gift of Patricia Cromiller, 2001.511

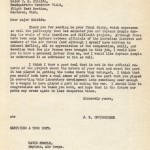

- Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, chief scientist for the Manhattan Project, wrote this letter to Major C.S. Shields and Captain David Semple thanking them for their work in developing the atomic bomb. Gift of Patricia Cromiller, 2001.511

- This service jacket was worn by Army Medical Corps physician Dr. Charles Prosser, Jr., who worked at both Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, without ever knowing what the men and women he treated were working on until the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Gift of Louise Prosser in Loving Memory of Dr. Charles S. Prosser, Jr. 2011.058

- Military members working on the atomic bomb at Los Alamos wore this patch, whose design represents the splitting of the atom. Gift of Louise Prosser in Loving Memory of Dr. Charles S. Prosser, Jr. 2011.058

This post by Curator Meg Roussel