SciTech Tuesday: The 75th Anniversary of the Doolittle Raid

Seventy-five years ago today, on April 18, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle led a group of 16 B-25s filled with 79 men (in addition to himself) on the first bombing run of Japanese territory in World War II.

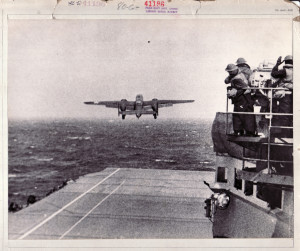

Medium bombers had not been launched from a carrier before—carriers had only 467 feet of takeoff space. The idea for the mission came from Navy Captain Francis Low, who saw planes landing and taking off from an airstrip in Norfolk, Virginia, where a carrier’s outline had been painted on the runway for practice. He noticed that the medium bombers could often take off before crossing the carrier’s outline. Doolittle was put in charge of planning a mission to boost American morale and to damage Japanese confidence.

The B-25 was chosen, even though it was new and untested, because of all the two-engine bombers it was the most capable of taking off from an aircraft carrier. Other planes had longer ranges, but their wingspan was longer and would limit the number of planes that a carrier could fit. The aircraft were modified so that they could complete the 2,400-mile mission with a payload of 2,000 pounds of bombs. The normal range of the B-25 was 1,300 miles. To extend their range they were equipped with extra fuel tanks, most of their defensive guns were removed, and their Norden bomb sights were removed, too.

The 15 planes took off from the carrier Hornet in the western Pacific, flew over Honshu to target military installations in Tokyo and other cities, and then headed for mainland China. The planes each carried three high-explosive bombs and one incendiary bomb. The planes had to take off hours sooner and hundreds of miles farther from Japan than expected when Japanese airplanes were spotted from the Hornet. The Hornet was accompanied by the Enterprise and her escort ships, which comprised Task Force 16 under the command of Admiral William Halsey. Landing in Vladivostok would have made a shorter trip, but the Soviets had signed a neutrality pact with Japan in 1941.

The planes flew over Honshu at about 1,500 feet, receiving little resistance, about six hours after their launch. They dropped several bombs around Tokyo, and others near Yokohama, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka. After dropping their bombs, all but one plane turned southwest toward eastern China. One B-25 was low on fuel and headed toward Vladivostok. That plane landed on a base at Vozdvizhenka, where the plane was captured and the crew interned. Aided by a strong tailwind of about 29 miles per hour, the remainder of the B-25s reached the Chinese coast about 13 hours after launch. Without that tailwind, they probably would not have made it to China. Over land, the pilots crash-landed or bailed out. Three men died while bailing out, two perished at sea, and one over land. Three men were executed after capture by the Japanese, and another five were held as POWs. Of those, four survived to the end of the war and were liberated in August 1945. The remainder were rescued, often aided by Chinese, who suffered severe retribution afterward.

Doolittle feared that his loss of all 16 planes would lead to a court-martial. Instead, he was promoted to brigadier general while still in China, and awarded the Medal of Honor by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt upon his return home.

The raid caused little material damage to Japan. However, it did have its intended effects—to boost morale in the United States and to dent Japan’s confidence. It also led to the Japanese military’s determination to hold the central Pacific, leading to the Battle of Midway and the overextension of Japanese naval forces in that direction.

The last surviving Doolittle Raider is retired Lieutenant Colonel Richard Cole, who was Doolittle’s copilot. He is now 101 years old.

Cole’s Museum oral history is here.

- The nose glass of this B-25 was broken in training when the plane crashed into a large bird while aloft.

- A crew in training outside their B-25.

- An aerial view of B-25s flying over New Guinea.

All images from the collection of The National WWII Museum.

Learn more here about the Museum’s B-25.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum

- Posted :

- Post Category :