Doolittle’s Daring Raiders Lift the Gloom that Descended After Pearl Harbor

April 18, 2017, marks the 75th anniversary of the Doolittle Raid. Below is an essay by Keith Huxen, PhD, the Museum’s senior director of research and history, that frames the importance of the daring raid to the Allied cause in World War II. The essay appeared in the spring 2017 issue of V-Mail, the Museum’s quarterly newsletter for Members. Visit the links below the essay to explore more about the Doolittle Raid via the Museum’s Digital Collections. Learn more about the benefits of Museum membership here.

In December 1941, Americans were reeling after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and military onslaught across Asia and the Pacific. Emotionally, the nation was in shock, and a deep, consuming anger quickly set in as the people came to comprehend the enormity of the damage in Hawaii. Americans resolved to fight, and thirsted for revenge. However, despite their newfound determination, Americans would find that they would have to travel through a long, dark valley of war.

The emotions of the time were perhaps best encapsulated in the experience of USMC Captain Henry T. Elrod, who flew with VMF-211 to Wake Island only days before the Japanese attacked. Fighting valiantly and repeatedly against the odds in the following days, Elrod distinguished himself on several occasions, once conducting a solo attack against 22 enemy planes and downing two Zeroes, and on another occasion sinking the Japanese destroyer Kisaragi from his fighter aircraft with small-caliber bombs. After all American aircraft were inoperable, Elrod organized beach defenses to meet the enemy. It was during combat with invading Japanese forces on the beach that Elrod was killed on December 23, 1941. Wake Island surrendered that day.

For his heroism, Elrod would be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, but his personal trial was symbolic of the desperate situation the Allies faced as 1942 dawned. On Christmas Day 1941, Hong Kong was taken. The Japanese overwhelmed Australian forces on Rabaul, a key base, in late January. In February, the United Kingdom was stunned as Singapore surrendered, and then the Japanese bombed ports in Australia. In March, the Dutch East Indies, with its vital supplies of oil, rubber, and tin, fell to the Japanese.

The biggest American domino in the chain was conquered next. The Japanese had attacked the Philippines as part of their sweeping attacks on December 7–8, 1941. Now, after five months of fighting, Filipino and American troops on the Bataan peninsula surrendered on April 9. A small group of stout American and Filipino forces continued to resist from the island of Corregidor in Manila Bay. Unbeknownst to the American public at the time, however, the captured troops were then subjected to the brutal Bataan Death March.

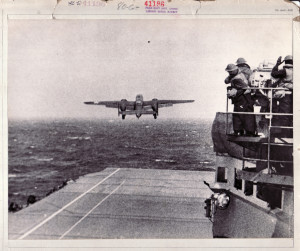

At last, the first thin ray of light pierced the dark valley of continuous defeat. On April 18, 1942, American air forces under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle conducted a surprise raid against Japan. The raid was daringly launched with stripped-down B-25 bombers launched from carriers too far away for the crews to safely return. The bombing damage done in Tokyo and other sites was actually insignificant, but the jolt of finally striking back at the enemy, coupled with the courage of Doolittle’s aviators embarking upon a one-way mission to China (three captured Raiders were eventually executed), spurred a massive psychological lift for Americans weary of bad news.

Doolittle’s Raiders provided a flicker of hope for the future, but the valley of war still had dark pathways ahead. On May 6, 1942, Corregidor fell to the Japanese, sealing Allied defeat in the Philippines for the time being (guerrilla groups would continue to fight on throughout the war).

With many battleships sunk in Pearl Harbor, the US Navy was forced to rely upon submarines and aircraft carriers in a new naval warfare. Beginning the day following Corregidor’s fall, on May 7–8, 1942, the US Navy and Imperial Japanese Navy fought the Battle of Coral Sea. It was indecisive in that both sides scored against each other’s all-important assets—the United States sank the Japanese light carrier Shoho but lost its own carrier Lexington—in the first battle in naval history in which the fleets did not sight each other and combat was conducted solely through the air.

Halfway through 1942, the United States was still without a significant victory on the battlefield, and Americans were wondering how long this situation could be endured. Our enemies were growing stronger every day. They could not know it at the time, but the terrain of the dark valley of war was about to take a dramatically different shape when US forces next engaged the enemy off a small island in the Pacific, a place called Midway.

Links:

Watch eyewitness accounts of the Doolittle Raid from the Museum’s collection of oral histories here.

Watch a panel discussion about the raid from the Museum’s 2011 International Conference on World War II here.

A multimedia journey into the post-Pearl Harbor darkness, with videos, photos, and Museum artifacts, is here.

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags :

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.