SciTech Tuesday: The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Los Angeles

The night of February 24, 1942, and the hours before dawn of the 25th, the sky over Los Angeles was lit by search lights, the city was under a blackout, and more than 1.400 shells were shot from .50 caliber guns into the air. When the all-clear was sounded at 7:21 AM on the 25th, the only casualties were buildings and cars hit by shell fragments, and 3 civilians killed in car accidents.

The immediate cause of the false alarm was a rogue weather balloon. When spotted from the ground by nervous watchers, lit from underneath by search lights, it was identified as an enemy aircraft.

The real cause was nervousness and a heightened watchfulness that resulted from events on the previous day, a short ways up the California coast.

On the evening of February 23, President Roosevelt delivered a fireside chat radio broadcast. Less than three months since the attack on Pearl Harbor, the nation was anxious, and in the midst of preparations for war. In the speech, Roosevelt said “…the broad oceans which have been heralded in the past as our protection from attack have become endless battlefields on which we are constantly being challenged by our enemies.’’ In the weeks since Pearl Harbor the United States had heard more bad news of advancing Japanese forces across the Pacific Ocean and Asia, and U-boat attacks from the German Navy in the Atlantic.

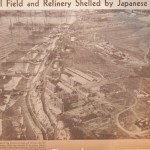

Perhaps as a means to undermine Roosevelt’s confident speech, a Japanese submarine patrolling the West Coast surfaced offshore north of Santa Barbara, and launched 13 shells towards oil wells and equipment in Ellwood, CA. It completely missed the gasoline plant there, caused minor damage to the piers and wells, and stayed 2,500 yards offshore, but the submarine’s impact on popular anxiety was great. The night of the shelling the Army Air Force sent a handful of pursuit planes and bombers to find the submarine, but was loath to commit more forces.

Intelligence supplied by loyal Japanese Americans had suggested that there might be some action to disturb the President’s speech. It also suggested that Los Angeles might be attacked the next night. The state of readiness itself led to the false alarm.

Confused reports from the night of the event, secrecy after it, and anxiety led to many conspiracy theories. This might even be counted as one of the first major events in the history of UFO conspiracies. Radar sightings of the objects triggering the artillery fire suggested they were moving far too slowly to have been planes. The use of radar for these purposes was new, and inexperienced operators may have been part of the problem. Visual sighting under night conditions is unreliable. Without context objects like weather balloons in the sky, especially with uncertain lighting, are difficult to scale.

The event led to better coordination of civilian and military defenses on the West Coast, and to more surveillance of activities and objects around plants and other installations near the shore. It might also have contributed to popular sentiment in support of Japanese Internment. Roosevelt had authorized Executive Order 9066 just days before.

- A clipping from the Los Angeles Times the day after the Battle of Los Angeles. From the Los Angeles Times.

- A period photo of a Japanese submarine similar to the one used in the Ellwood Bombardment. From Wikimedia Commons.

- Newspaper headlines from the Santa Barbara News after the Ellwood Bombardment.

- A newspaper clipping about the Ellwood Bombardment. From the Santa Barbara News.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum