SciTech Tuesday: From Christmas Lights to Proximity Fuses

During WWII many factories changed their production from peacetime to wartime products. One General Electric factory in Cleveland, OH, went from making Christmas lights to a top-secret electronic device protected by security surpassed only by the Manhattan Project and the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

From 1939-1942 radar researchers in England tested a variety of devices that might be used to improve the effectiveness of anti-aircraft artillery. These artillery cause the most damage when they explode a short distance from their target. Detonation timing was based on a set timer or on impact, neither of which were efficient.

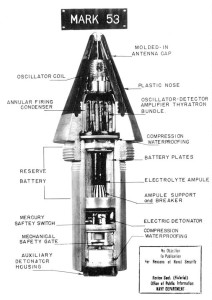

The idea being researched in England was that a small radio transmitter, coupled with an equally small receiver, could be mounted on the nose of a missile. The transmitter’s signal would bounce back, and the interaction of the sent and received signals could be used to estimate proximity to a target. These electronics required a battery, and had to be tough enough to withstand launch. The English called the technology VT, or Variable Timer fuzes. It was later called a Proximity fuse.

The Tizard mission brought the plans and data from these tests to the US, and the NRDC prioritized development and production of the fuses. Some improvements were made, and by 1944 a significant proportion of all US electronics output was parts for Proximity fuses. These were made by many companies, including RCA, Eastman Kodak, and Sylvania, in the the first mass-production of printed circuits.

Julius Rosenberg stole some of this technology and passed it to the Soviet Union. The US military was so concerned about the secrecy of Proximity fuses that they limited its use where German forces might capture unused or unexploded devices.

Vannevar Bush, head of the Office of Scientific Research and Development during the war viewed Proximity fuses as of special importance to Allied success, crediting them with a sevenfold increase in effectiveness in defense against Kamikaze attacks, neutralization of V-1 attacks, and in its use in the Battle of the Bulge against land troops.

The triggers were so sensitive that they occasionally took out unfortunate seagulls. Eventually Proximity fuses were used in bombing Japanese cities, and today’s current weapons use similar principles for detonation.

The Germans had been developing similar technology in the 1930s, but dropped it for other weapons with more immediate promise shortly after 1940.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum.

Leave a Reply