SciTech Tuesday: The Ring of Fire and WWII

On September 1, 1923 at 11:58 AM an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.9 occurred in a bay just south of Tokyo. Tokyo and Yokohama, a relatively young port city with a strong international influence, were the closest large population centers. After the earthquake a tsunami with an 11 meter high crest hit Yokohama and surrounding areas. Fires spread throughout Tokyo and Yokohama, and with water mains broken by the quake there was no way to fight them. The earthquake led to a 2 meter uplift on the coast, and a 4.5 meter horizontal displacement of land. Even though it lasted only 14 seconds, it was a huge amount of energy released. 570, 000 homes were destroyed, and more than 140,000 people were killed. With telegraph technology connected to radio, news from Japan to the countries of the West moved rapidly. The US and other countries mobilized support for victims of the earthquake within 24 hours.

Japan had annexed Korea more than a decade earlier, and, in the months before what came to be called the Great Kanto Earthquake, a group working for the liberation of Korea had been conducting terrorist attacks. Rumors spread in the aftermath of the quake that Koreans were looting and starting fires. Violent attacks on Koreans, and anyone thought to be Korean, followed. The government tried to protect Koreans, but also covered up any attacks that occurred.

This event, and Japan’s dependence upon the West for support in recovery, fueled growing nationalism. The expansion of Japanese influence and the later war in the Pacific can be traced in part to this earthquake in 1923.

Earthquakes were, and still are, common in that part of the Pacific. So are volcanoes. These geological factors shaped the islands, and when US troops fought there in WWII these conditions shaped logistics, and even the path of the war.

There is a diamond shaped continental plate—the Philippine plate-pinned between the much larger Pacific and Eurasian plates. The Pacific plate is moving slowly but relentlessly west, pushing the Philippine plate ahead of it. Where the plates meet the Pacific sinks below both the Philippine and Eurasian plates, and the Philippine plate dives under the Eurasian plate. This pattern of plate convergence is called subduction, and leads to earthquakes and volcanoes. Where the plates come together in the ocean they form volcanoes which can emerge from the ocean, creating islands. From New Guinea to the Marianas and Iwo Jima (on the east side, between the Philippine and Pacific plates), from the Philippines to Okinawa and up (on the west side, between the Eurasian and Philippine plates) to Japan (split by the Eurasian and Pacific plates), all those islands are formed from volcanic activity. Some of those islands are very old, mostly dead, volcanoes, and the coral reefs that surround them (like Tinian, or the Bikini atoll). Others are younger, and form very high tropical peaks (like in the Philippines). Iwo Jima, which in its original Japanese name means ‘sulfur island,’ was formed by slightly different volcanic activity that led to its peculiar geography. There is abundant groundwater on Iwo Jima, all of it very hot and enriched in minerals. The frequent volcanic activity there is mostly steam created by the interaction of groundwater and magma (molten rock).

The geological theory that explained volcanoes and earthquake patterns, called Plate Tectonics, wasn’t solidified until the late 1960s. So troops went into this zone, where there were more than two dozen large earthquakes (> 6.0) between 1940 and 1946, without any way to predict what was going on, or any understanding of what each stop on the island-hopping path to Tokyo would bring.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum.

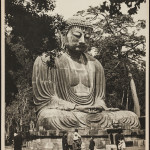

- This very famous landmark in Japan was moved 2 m and its base destroyed by the 1923 earthquake. From Wikimedia commons

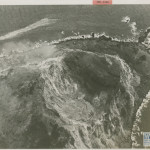

- An aerial view of Iwo Jima from the opposite side, after the battle. From the collection of the NWWII Museum

- A look inside Mt Suribachi, the large volcano on Iwo Jima. From the collection of the NWWII Museum

- An aerial view of Iwo Jima with landing craft ready for invasion. From the collection of the NWWII Museum

- The headline of the NY Times reports on the Great Kanto Earthquake, and also foreshadows developments in Europe

Leave a Reply