SciTech Tuesday: Nomination for best technology in a supporting role—the Norden Bombsight

When Louis Zamperini flew in World War II one of his jobs was to use his Norden to target enemy ships and structures. When he and the rest of his plane’s crew went missing the CO who packed his personal effects confiscated the photos in his locker that showed him in the plane next to his Norden bombsight. The Norden’s technology was a tightly held secret. So secret that bombers were instructed to use their sidearm to destroy them before they found their way into enemy hands.

In theory the Norden could target with an error of 23 m (75 ft). This led to the US military strategy of targeted bombing instead of area bombing as the British and German forces used. With targeted bombing fewer artillery could be used, and bombers could stay at high altitudes, safer from anti-aircraft fire.

In practice, in combat, the Norden was much less accurate than estimated. In combat it had a practical accuracy of 370 m (1200 ft). The Navy used dive-bombing and the Army Air Forces used a lead bomber to increase practical accuracy.

Experience with aircraft in bombing in World War I showed that a major targeting problem was leveling the aircraft. Trajectories could be calculated with knowledge of airspeed, groundspeed, and altitude, using analog computers. But if the plane was not flying level to the ground the calculation would be way off. The Navy contracted Carl Norden, a Dutch engineer trained in Switzerland who came to the US in 1904, to help solve the leveling problem.

Norden was an expert with gyroscopes. A gyroscope uses the angular momentum of a spinning disk to maintain proper orientation. In plain English—a spinning wheel resists turning. That resistance to turning can be used to keep an object going in one direction. Before GPS, gyroscopes were used to measure the change in course of a vehicle.

Gyroscopes held the apparatus level while the bomber sighted his target. A mechanical computer in the bombsight calculated for the bomber. He dialed in wind speed and direction, altitude and heading, and the computer calculated his aim point. One way that the Norden improved upon other devices was that the bomber found the target in his telescope, and then using the settings he entered, the Norden employed a rotating prism to keep the target in the bomber’s sight. In this way it used two angles, one based on altitude, airspeed and ballistics, and another based on ground speed and heading. The difference between these two angles would decrease as the aircraft approached the target. When the difference was zero, the Norden dropped the bombs.

The Norden also connected to the plane’s autopilot. When engaged, it took over flight controls to correct for any change in airspeed and to maintain heading. While this improved accuracy, it made it dangerous for crews encountering anti-aircraft fire or under attach from fighters.

There’s a description of how Louis Zamperini used the bombsight in Unbroken:

“Louie was trained in the use of two bombsights. For dive-bombing, he had a $1 handheld sight consisting of an aluminum plate with a peg and a dangling weight. For flat runs, he and the Norden bombsight, and extremely sophisticated analog computer that at $8000, cost more than twice the price of an average American home. On a bombing run with the Norden sight, Louie would visually locate the target, make calculations, and feed information on air speed, altitude, wind, and other factors into the device. The bombsight would then take over flying the airplane, follow a precise path to the target, calculate the drop angle, and release the bombs at the optimal moment. Once the bombs were gone, Louie would yell ‘Bombs Away!’ and the pilot would take control again.”

There’s also a great article in the NY Times that describes how Laura Hillenbrand learned about Norden bombsights.

Before the war, from 1932 to 1938, about 120 bombsights were made each year in the company’s New York City engineering lab. These were primarily handmade, mostly by German and Italian immigrants. The lab was converted to a production facility after Pearl Harbor, and produced almost 7000 bombsights in 1942. The majority of this production went into Navy aircraft, until in 1943 the Navy declared it had a surplus. At this time the Army Air Forces cancelled its contract with a competing firm and took delivery of everything that Norden could produce. Norden built more factories, and added licensed manufacturers. At the end of the war, 72,000 Norden bombsights were built for the Army Air Forces, billed at the rate of $8800 each.

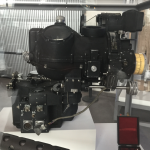

We have several Norden bombsights here in our collections, and on display. There’s one in The Road to Berlin, and two in the US Freedom Pavilion:Boeing Center. There you can see one in the nose of the fuselage of the plane “Overexposed,” just as the bomber used it. Next to the fuselage there is a Norden in a case with some other technical equipment.

Radar and bombs with their own targeting mechanisms eventually replaced the Norden bombsight, but they were used in the Korean war, and even on bombing runs in the Vietnam War.

- The Norden bombsight on display in The Road to Berlin.

- A closeup of the dial on the Norden in The Road to Berlin.

- From The US Freedom Pavilion:The Boeing Center, a Norden bombsight in the nose of the Overexposed fuselage.

- On display in The US Freedom Pavilion:The Boeing Center, a Norden with autopilot attached.

- From Wikipedia, a poster labeling the parts of the Norden bombsight.

Posted by Rob Wallace, STEM Education Coordinator at The National WWII Museum

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags :

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Leave a Reply