Day of Infamy: Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

December 7, 1941, is a date which retains its unique power in the national consciousness of the American people because it marks our entryway into the Second World War and ultimately the pathway to the dominant position of the United States in world affairs, the Pax Americana of the twentieth century. The Japanese attack decisively ended American neutrality and our efforts to isolate the nation from the previous decade of troublesome world affairs. To many, it is the day the United States shed its innocence and naiveté, and shouldered the burdens of world leadership.

For most Americans, however, the Japanese attack was a surprising gateway to this destiny. Events in remote Asia were not seen as an immediate threat to the United States at the end of 1941. Instead, it seemed more likely that the United States would be drawn into war with Nazi Germany, as the American convoys carrying Lend-Lease to Great Britain came under fire from the German navy. Instead, war came to Americans in an unanticipated, blinding flash from across the Pacific, an attack that succeeded beyond the imagination of its planners in many respects, an attack that caught the American military unawares and in an embarrassed state and exposed condition. The story of the missed signs, misinterpretations, misunderstandings and many ironic passages which all combined to lead to Pearl Harbor is a vast tapestry.

The Japanese Course to War

The Japanese people were the most economically, industrially, technologically, and militarily advanced nation in Asia. Going back to the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government had sought to integrate the best elements of Western culture within their own Confucian cultural framework. These ideas included adopting Western styles of dress to Western attitudes towards science and industry. During the Great War in Europe, the Japanese joined in with the Allied powers in 1914, exploiting the opportunity to expand into China at the expense of the German colonial possession of Shandong province, and taking small German-held islands in the north Pacific (in the Marshalls, Carolines, and Marianas). But at the Versailles treaty negotiations in Paris, the Japanese delegation was disillusioned when the racial equality clause was eliminated from the Covenant of the League of Nations charter. The Japanese moved to consolidate their imperial holdings.

The central facts of Japan’s world position were that it was an island nation with an expanding population but lacking in necessary natural resources. The Japanese needed agricultural land, tin, rubber, and most importantly oil supplies to meet their needs. The Japanese viewed themselves as the sun whose rays would cast out over Asia and the Pacific in a Japanese empire. A belief in the racial supremacy of the Japanese over other Asian peoples added a powerful inducement to military expansion. In 1931 the Japanese invaded Manchuria, and then dropped their membership in the League of Nations. In July 1937, the Japanese invaded China, but the vast hinterlands and population of the Chinese beyond the coastal regions kept the Japanese from establishing a clear-cut victory. The situation mired into a stagnating “China Incident” from which the Japanese appeared unable to extricate themselves. They needed the economic resources and military strategy which would bring them the desired victory and regional dominance.

These were the political and military circumstances which the Japanese faced by early 1940 in Asia. But it was at this point that events in Europe also began to influence top thinking in the Japanese government. The great success of Hitler’s sweep across western Europe in the spring of 1940 provided a military model and inspiration for the fast, lightning strike against a vast territory. The Japanese wished to duplicate this feat across Asia, but their strategic thinking faced a crossroads by the summer of 1940: should they turn northward and invade their traditional enemy, the Soviet Union, striking for the material resources of northern Asia (the “Northern Strategy”)? This would bring them into war with the Soviet Union, a nation that was technically allied with Nazi Germany at the time. Or should they turn southward and strike in a great sweep across Southeast Asia and the southwestern Pacific island chains (the “Southern Strategy”)? This would bring them into war with the British over possessions such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and British Borneo; with the Dutch over Dutch Borneo (rich in oil resources); and with the United States over the American-held Philippines. Of these nations, the Dutch could not be a threat, as they were currently occupied by Nazi Germany, and Great Britain was desperately fighting the Nazis for their existence. This left the United States standing in the way of Japanese imperial ambitions. The Japanese government decided that a Southern strategy was preferable, and implemented courtship of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy as potential allies. In September 1940, the Tokyo-Rome-Berlin Axis was formed through the Tripartite Pact.

The adoption of the Southern strategy by Japanese leaders also instigated a fatalistic attitude towards war with the United States. The American position was that in order to ease tensions between the two nations, the Japanese would have to forego their imperial ambitions, including the evacuation of China. The Japanese were not prepared to accept the national humiliation and shame in such a martial withdrawal. The American response to Japanese aggression was to gradually increase economic pressures upon Japan, beginning with the ban of American exports of key raw materials and minerals to Japan in 1940. By January 1941, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet, began to seriously prepare plans for the war with the United States, which he regarded as inevitable, through a surprise attack upon the American Pacific Fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. There were tremendous internal political obstacles and technical problems to be overcome before such an attack on Pearl Harbor could be feasibly adopted and pursued by the Japanese government. One outstanding achievement the Japanese overcame was to redesign torpedoes and dive patterns to navigate the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. Perhaps the greatest irony was that Yamamoto himself wished to avoid war with the United States, as he believed that resource-strapped Japan could not possibly hope to prevail in a lengthy war with the resource-rich and industrially advanced United States. Nonetheless, the adoption of the Southern strategy and planning for the Southern Operation held out the hope that if Japan could sweep through Southeast Asia and the Southwestern Pacific islands, the Japanese might acquire the necessary natural resources that would allow them to effectively compete with the United States in war, and a surprise blow might shake American confidence so far as to weaken American will to resist a Japanese fait accompli.

Summer 1941 saw the pace of conflict quicken. On June 22, 1941, Hitler launched the invasion of the Soviet Union. The German war in Russia eliminated from influence in Japan the last advocates of the Northern strategy. Aware through intelligence intercepts of Japanese cables that the Japanese planned to invade French Indochina, on July 23 the Roosevelt administration informed the Japanese that they would no longer conduct the unofficial peace discussions which had been percolating between the two governments for two years, and on July 26 the administration froze all Japanese assets in the United States and banned the export of high-grade oil (used for airplanes and ships) to Japan. On July 28, the Japanese took a key step in their Southern strategy by invading French Indochina. The rest of the Southern strategy and targets beckoned, but Japan found itself unable to purchase the needed oil supplies which would power their military conquest, with reserve oil supplies daily dwindling. In August attempts by diplomats to broker a meeting between the President and Prince Konoe (head of the Japanese government) foundered. But at this very time, the Japanese military leaders were taking steps towards a final strategy out of the impasse they believed they were in. After a Liaison meeting between the Army and Navy and then securing the approval of the Emperor in a September 6, 1941 Imperial Conference, the Japanese military leaders effected a policy which in their eyes would determine the Japanese national destiny. While the plan allowed for six weeks of diplomatic negotiations to potentially settle the conflict short of war (negotiations which the military leaders expected to fail, especially given the short time constraints), the plan committed the Japanese to a policy of war against the United States.

By October 15, with a diplomatic agreement to the American-Japanese conflict over the future of Asia unsettled, the Konoe government in Japan fell, and was replaced by Army Minister General Tojo Hidecki. But with war imminent and the Navy showing signs of uncertainty over the likelihood of a successful attack at Pearl Harbor, Tojo recognized that his new government would have to re-visit and reconstruct support for the decision of September 6. The Liaison Conference between Japanese army and naval leaders met almost continuously in the last week of October, reviewing three potential options. At the November 1 meeting, after seventeen hours, the decision was reached that war would commence in early December, barring any diplomatic breakthroughs prior to the end of the day on November 30. This timetable would be hidden from the Japanese ambassador to the United States in order to ensure surprise; the Japanese fleet in fact left port over three weeks prior to the attack, assembling at sea to be in proper position when the time arrived. The Emporer acceded to the plan at the Imperial Conference on November 5, 1941. After the failure of diplomatic negotiations to produce a comprehensive settlement by the November 30 deadline, the Emporer again approved the decision to go to war on December 1.

December 7, 1941

At 7:53am on Sunday, December 7, 1941 (December 8 on the international dateline in Tokyo), Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, leader of the first wave of Japanese attack planes, sent the signal to the entire Japanese navy that the strike force had achieved maximum surprise: “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (“Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!”) A total of 183 Japanese attack planes in the first wave of the attack (170 more would be a half-hour behind in the second wave) swooped into the midst of the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. The Japanese began to wreak tremendous devastation. At 7:58am Commander Logan Ramsey at the Ford Island Command Center issued the radio message which awakened Americans to their predicament: “AIR RAID, PEARL HARBOR. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

A total of 2,403 Americans were killed in the worst attack upon American soil to that day; 1,178 were wounded. The Navy lost a total of 2,008 men killed (1,177 perished with the destruction of the U.S.S. Arizona). The Army lost 218 killed; the Marine Corps 109; and 68 civilians lost their lives. The Pacific fleet saw eight battleships, three light destroyers, three light cruisers, and four auxiliary ships damaged, capsized, or sunk outright. Between the Army Air Force and Naval Aviation, over 150 planes were lost. The Japanese lost a total of 29 planes in the attack.

There were many ironic and tragic factors in the American defense preparations which in hindsight might have prevented the Pearl Harbor attack or limited its destructive potential. This included the monitoring of the activities of Japanese spies in Hawaii by American law enforcement agencies; the limited access to and sharing of information gathered through the Magic code intercepts which various U.S. government entities held, but could not share to connect the dots to the larger strategic picture in Japan; and even accidental events such as the young untrained American officer who mistakenly identified the incoming Japanese attack as an expected incoming group of American B-17 bombers due from the West Coast.

And yet the Americans could be thankful that the attack was not worse. All of the American aircraft carriers had been out on maneuvers, and the Japanese failed to destroy any of them in the attack. The aircraft carrier would be the key instrument in the American effort to project its military power against the Japanese across the Pacific in the coming months. The Japanese, by the nature of their attack on Pearl Harbor, had shown the imaginative and tremendous destructive power which carrier fleets and aircraft could deliver. However, the Japanese had also failed to envision the tremendous success their attack had achieved, and had not been prepared to follow through with an even more damaging military possibility: landing an occupying Army force at Pearl Harbor. Had the Japanese been that audacious, the American military would have found itself attempting to launch the invasion of Hawaii from California, and the long Pacific campaign would have become much more difficult and longer.

For the Japanese, it should be remembered that the Pearl Harbor attack occurred in conjunction with attacks on American-held Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines all launched on December 7, 1941. The Pearl Harbor attack, however, holds a special interest and place in the Japanese operations because none of the other Japanese attacks or strategy make sense, or are achievable in the long run, without its success. The American fleet could quickly be dispatched against a Japanese attack on Guam, Wake Island, or the Philippines (American intelligence services in fact were aware that the Japanese were planning on offensive measures against the United States, and thought that the Philippines would be the likely target). But the Japanese goal through their Southern strategy was to grasp the Greater Southeast Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, or Japanese Empire of the Pacific. The Japanese military leaders responsible for launching the war against the United States believed that if they could immobilize the American Pacific fleet, this would give them to time to sweep through their real objectives: Borneo, Philippines, New Guinea and the rich natural resources that would secure and promote Japanese military power in the region. Once the United States recovered from the blow, Japanese leaders believed that the Americans would find the prospect of rolling back this Japanese onslaught too difficult to attempt. Instead, they hoped that the United States would then accept a Japanese offer of a negotiated peace, and the Japanese would retain their new empire in Asia intact.

The American Response to Pearl Harbor

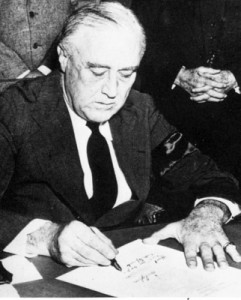

The Japanese calculation of the American response to Pearl Harbor proved to be a great political mistake. The American people were instantly and completely unified around the cause of avenging Pearl Harbor and defeating the Japanese. President Franklin D. Roosevelt requested and received Congressional approval of a Declaration of War against the Japanese Empire in an emergency special session of Congress the following day, December 8, 1941.

The Pearl Harbor attack did allow the Japanese to pursue their Southern strategy successfully for over seven months. The Japanese literally ran riot through Southeast Asia and the Southwestern Pacific islands as a virtually unstoppable force in the aftermath. This included the Japanese invasion of the American Philippines, which showcased the Bataan Death March as the treatment which victims of Japanese aggression could expect in the maintenance of their empire. It was not until the battle of Midway in June 1942 that the United States was able to halt the Japanese momentum, and then begin the long slog back across the Pacific ocean towards mainland Japan in brutal island fighting beginning at Guadalcanal in August 1942.

But the passions unleashed in the United States in regard to the Pearl Harbor attack never cooled for the rest of the war, and in fact established and maintained an American sense of mission throughout the Pacific war. The Japanese triumph at Pearl Harbor was also the strategic mistake which ultimately brought about the destruction not just of the Japanese Empire, but the physical decimation of the Japanese homeland itself. And in bringing a reluctant United States into the Second World War, Pearl Harbor became the event which allowed and ensured that the remainder of the twentieth century would become the American century.

Keith Huxen, Ph.D., is the Senior Director of Research and History at The National World War II Museum.

- Posted :

- Post Category :

- Tags : Tags: 1941, FDR, Hitler, Keith Huxen, Pearl Harbor, Tojo

- Follow responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

3 Responses to “Day of Infamy: Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941”

Maxie Wells says:

Andrea Pitre posted this on Facebook, and I really enjoyed it. Good research and writing, Dr. Huxen!

Kristin Semmens says:

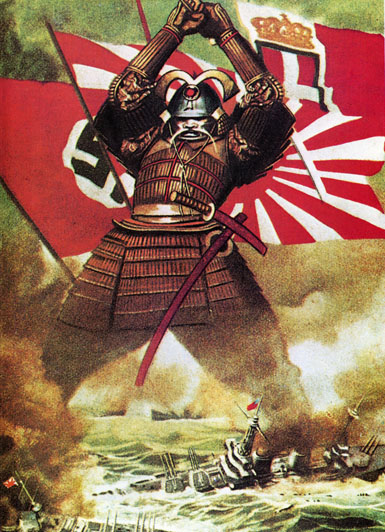

Could you please let me know something about the Samurai warrior poster? Is it an American poster?

Dr. K. Semmens

Kacey Hill says:

It is a Japanese wartime propaganda poster. You can find it here – http://www.psywarrior.com/JapanPSYOPWW2.html